Tuesday was the first day of early voting in Georgia. NPR’s Stephen Fowler reported that by 10:29 a.m. more than 71,000 Georgians had already voted. By the end of the day, the Atlanta Journal Constitution’s Greg Bluestein was reporting that “more than 300,000 Georgians cast ballots on the first day of early voting - *obliterating* surpassing the previous record.” Georgians got out and voted.

Tori Silas, the Chair of the Cobb County Board of Elections and Registration told me that she’d heard there were some early problems with equipment when the polls first opened Tuesday morning at 7:00 a.m. By 8:15 a.m., when she drove by to check out a local polling place, there was a line wrapped around the building with waits of up to 90 minutes to vote, while election workers sorted the problem out. Silas told me people stayed in line so they could vote.

As early voting was getting underway, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Robert McBurney was gearing up to take action in two of the election-related lawsuits in front of him. The bottom line: The good guys won today in Georgia—the people who want our elections to be conducted fairly and to ensure that when a voter casts a ballot, it will get counted.

Bear with me because there is a lot to get through tonight, but each of these cases is worth your time and attention.:

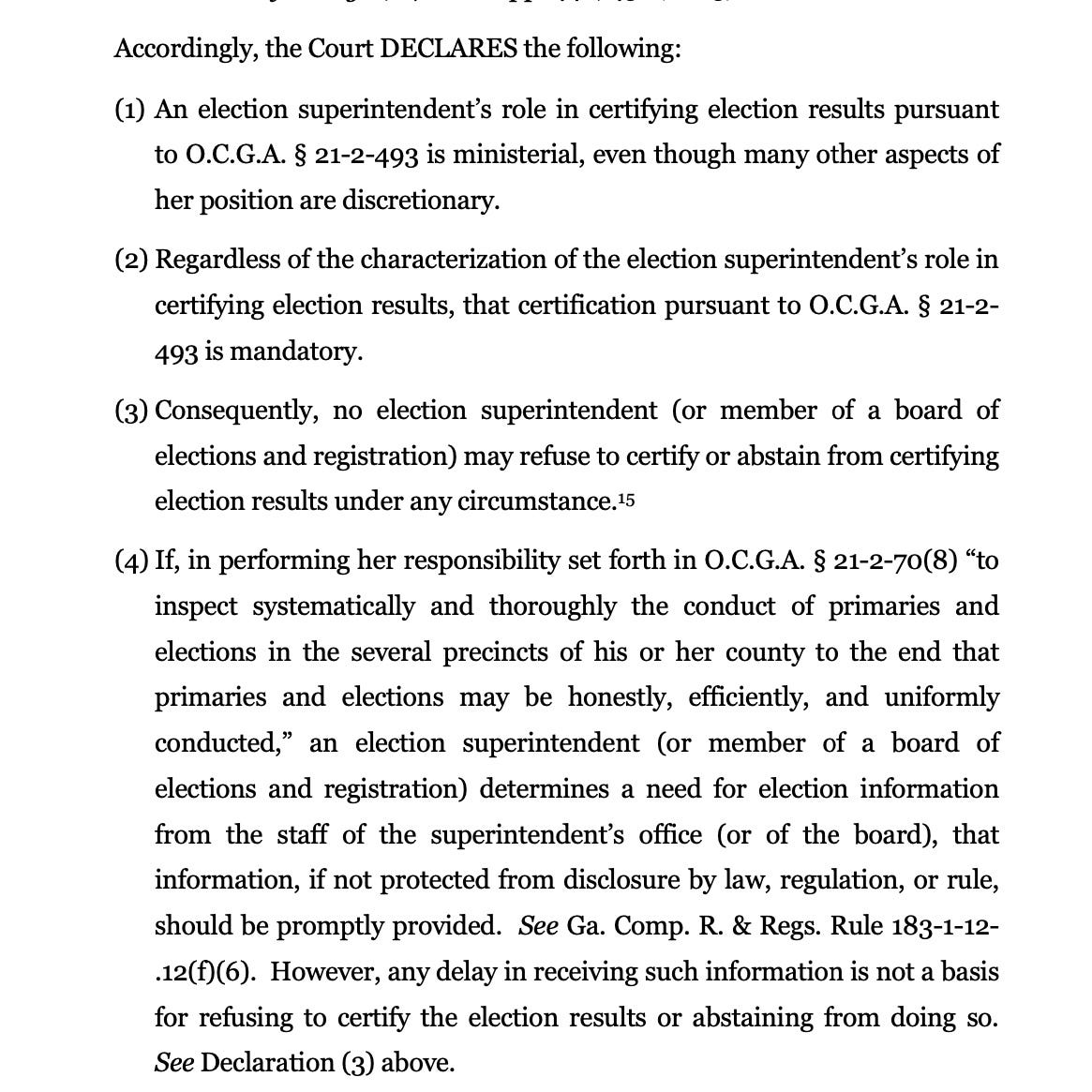

In Adams v. Fulton County, Julie Adams, a member of the Fulton County Board of Registration and Elections (FCBRE), asked the court to confirm she wasn’t obligated to certify the results of the election in her county.

We’ve discussed this issue before. The law is reasonably clear in this area. Certification is not something within the discretion of election officials, who are referred to as superintendents under Georgia law. Once the count is completed, they must certify it.

Judge McBurney confirmed this, writing: “some things an election superintendent must do, either in a certain way or by a certain time, with no discretion to do otherwise. Certification is one of those things.” Election officials conduct the counting of ballots, but once they are done they, “shall tabulate the figures for the entire county or municipality and sign, announce, and attest the same.”

This makes sense. There is abundant opportunity to explore any irregularities or challenges to the process, and they are guaranteed by Georgia law. For instance, a candidate can bring a challenge after the county certifies but before the states does, which is the next step in the process. The pretense that fraud or abuses could go unaddressed before the election results are final is simply incorrect.

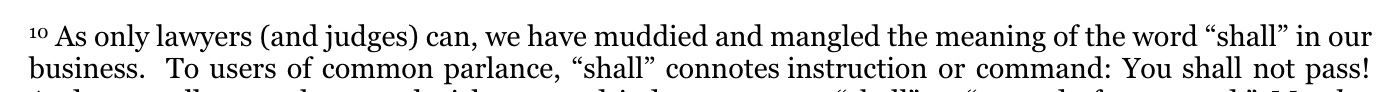

Apparently a “Lord of the Rings” fan, Judge McBurney noted in a footnote in his opinion that only lawyers could try to argue that where Georgia law says “shall” certify, “shall” means something other than it must be done. He wrote: “As only lawyers (and judges) can, we have muddied and mangled the meaning of the word ‘shall’ in our business. To users of common parlance, ‘shall’ connotes instruction or command: You shall not pass! And, generally, even lawyers, legislators, and judges, construe ‘shall’ as ‘a word of command.’” Gandalf has spoken, and at least until Georgia’s appellate courts get their hands on McBurney’s decision, county boards must certify their results once the count is complete.

Of course, there has been concern that MAGA supporters in positions of power might refuse to certify election results, throwing the outcome of the presidential election next month into doubt. But courts understand, even if politicians don’t, that shall does mean shall, and we can expect that if some officials refuse to certify, lawyers for the campaign will be quick to go to court to force them to comply with the law.

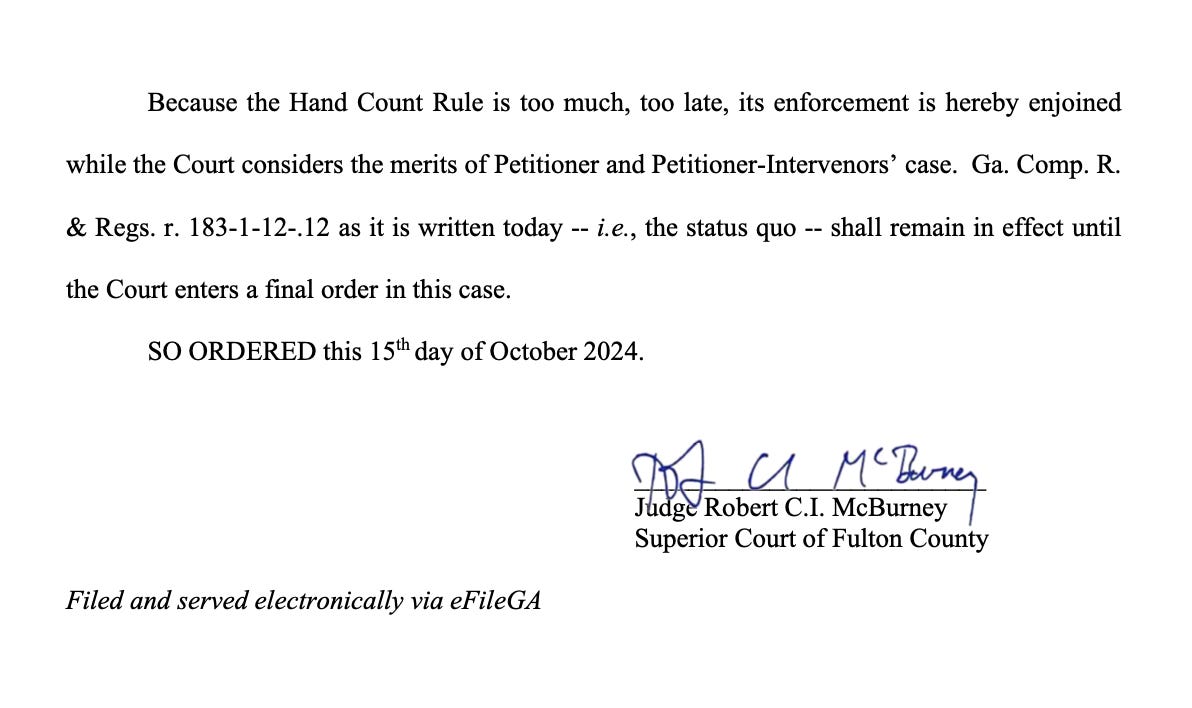

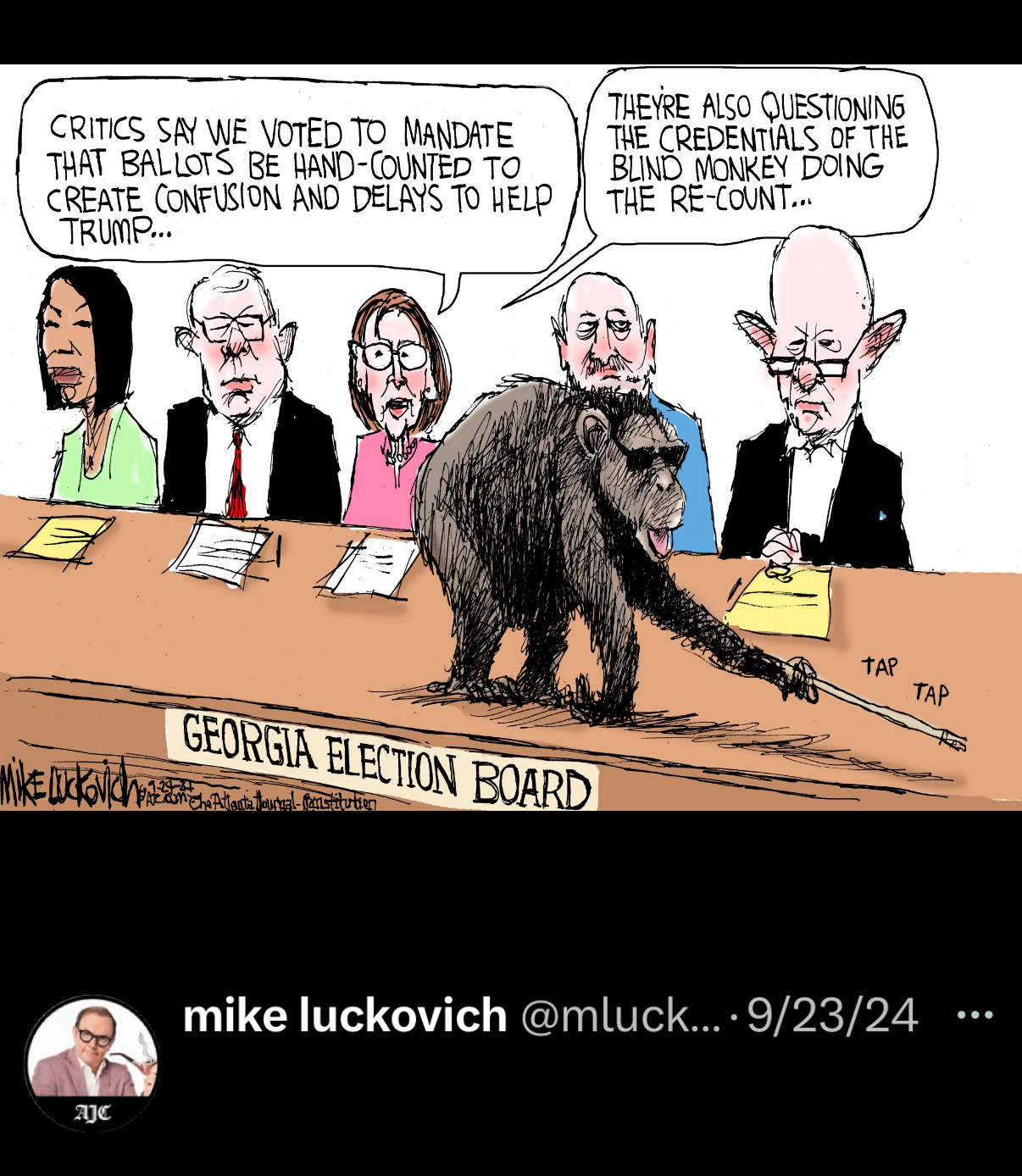

Cobb v. Georgia, also being heard in Fulton County Superior Court, is a challenge to six rules recently adopted by the State Election Board, including a rule requiring a hand count of ballots that would not go into effect until midway through the early voting period.

After a hearing today, Judge Robert McBurney, who is also assigned to this case, concluded that it was too close to the election to make a change like this and enjoined the hand count rule from going into effect for this election.

Something that you have to understand about the hand count is that it’s not a manual tally of the actual votes people cast. Rather, it’s a count of the numbers of ballots themselves, to make sure that the number of paper ballots, to be counted out into stack of 50, matches the amount of ballots cast in each precinct.

His decision:

“Today, the status quo is that there is no Hand Count Rule; it does not go into effect until 22 October 2024. Today is also the first day of early voting and only three weeks away from the general election. Should the Hand Count Rule take effect as scheduled, it would do so on the very fortnight of the election. As of today, there are no guidelines or training tools for the implementation of the Hand Count Rule. Nor will there be any forthcoming: the Secretary of State cautioned the SEB [State Election Board] before it passed the Hand Count Rule that passage would be too close in time to the election for his office to provide meaningful training or support … ; after passage and the unsurprising efflorescence of suits such as this one, the Secretary reaffirmed his inability to provide last-minute logistical support for the last-minute rule.”

He explained:

“[T]he public interest is not disserved by pressing pause here. This election season is fraught; memories of January 6 have not faded away, regardless of one’s view of that date’s fame or infamy. Anything that adds uncertainty and disorder to the electoral process disserves the public. On paper, the Hand Count Rule -- if properly promulgated -- appears consistent with the SEB’s mission of ensuring fair, legal, and orderly elections. It is, at base, simply a check of ballot counts, a human eyeball confirmation that the machine counts match reality. But that is not what confronts Georgians today, given the timing of the Rule’s passage. A rule that introduces a new and substantive role on the eve of election for more than 7,500 poll workers who will not have received any formal, cohesive, or consistent training and that allows for our paper ballots -- the only tangible proof of who voted for whom -- to be handled multiple times by multiple people following an exhausting Election Day all before they are securely transported to the official tabulation center does not contribute to lessening the tension or boosting the confidence of the public for this election. Perhaps for a subsequent election, after the Secretary of State’s Office and the 150+ local election boards have time to prepare, budget, and train -- but not for this one.”

The new rule passed at this late date would have been a nightmare for election officials to implement. Fulton County alone has 400+ precincts. The new law would have required three people in each precinct to conduct the count, so more than 1200 workers. But those people wouldn’t have received any training on conducting the hand count. Instead of the normal procedures where, once election days ends, the doors are locked and ballots are secured for transportation, polling places would have been required to accommodate members of “the public” who wanted to observe the process as they conducted the count. Election workers who had been on the job since as early as 5:00 a.m. would have to do the count without any guidance on how to separate themselves from observers for both their safety and the security of the ballots. They would have had to confront issues like where the resources for hiring security were going to come from and whether observers could take photos in the highly polarized environment that resulted in upheaval in the lives of Georgia election workers Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss in 2020. It would have been, as we say in the South, a hot mess.

But it’s also unnecessary. The number of voters and ballots cast is reconciled throughout the day. There is a count when voters show up and register on poll pad machines. The Ballot Marking Devices (BMD) machine that marks ballot keeps a count. And because the BMD prints out paper votes that are scanned, there is also a scanner count. In other words, there are periodic checks to make sure the numbers match up.

So why go to so much trouble to require a duplicative count and create a lot of chaos after the election is actually underway? The law was passed in the face of overwhelming objections from the Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Election Officials (GAVREO), the people responsible for administering Georgia’s election. How did it get passed? The three individuals on the State Board who voted to adopt it are the same three who got a shout out from Donald Trump when he was in Georgia for his August rally. We discussed that situation at the time in this post.

I asked Ms. Silas what she wanted people to understand about the election litigation in Georgia. She told me she wanted people to know that “election administrators and poll workers are dedicated to ensuring open, fair, transparent elections, and while we respect rules, adopting rules at the last minute that appear to only sow confusion is not a path forward. We thought this rule was a solution looking for a problem … Georgia voters can have confidence they will have safe, fair, transparent, and accurate elections.”

At the end of the day, there was also good news, at least partially, out of Alabama. Judge Anna Manasco, a Trump appointee, ruled that Alabama’s Secretary of State had to stop removing people from the voter roles based on his belief they might not be citizens. It’s the new Big Lie being set up to explain a Trump loss: “illegal aliens” are registering to vote. But of course, it’s just another lie.

Judge Manasco pointed out these people had been referred to Alabama’s attorney general for criminal investigation as part of the process. That obviously has an impact on an eligible voter, especially a new citizen who wants to make sure they don’t do anything illegal. It can step on whether they feel able to exercise their right to vote. But while she said the removals had to stop between now and the election, she declined to go further than that, leaving Alabama potentially free to recommence the removals after the election.

So far, 2,074 of the 3,251 people who received removal notices have been determined to be eligible to vote. And that’s just so far.

Tuesday was several months worth of litigation all in one day. And there’s more coming.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

At this point, it feels like Republicans have decided that winning elections is just too much work—much easier to rewrite the rules. Why campaign with unpopular ideas when you can just hit Ctrl+Alt+Delete on democracy?

Jimmy Carter made it to be able to vote in Georgia for Kamala Harris!