On Friday, the court of appeals in the District of Columbia affirmed, in part, Judge Chutkan’s gag order. The parts they affirmed are the parts that matter. Trump is prohibited from talking about witnesses in the case against him as it relates to their testimony and from impugning court personnel and prosecutors, excepting the Judge herself and Special Counsel Jack Smith.

The court offered good reasons for narrowing Judge Chutkan’s order. Even with that, it’s a big win for the prosecution. For one thing, upholding the gag order means that the gag order can be enforced if (when?) Trump violates it. And, by tightening up the order, the court of appeals has made it easier for the Supreme Court to affirm it when it hits their desks.

It’s easy to view Trump’s court battles the same way we would watch a ping-pong match, following the back and forth and keeping score after every exchange. But in reality, this is a much more complicated process involving positioning the case for a trial, a conviction, and an affirmance on appeal—that’s the long game. So while Trump’s lawyers tout the court’s decision to affirm “only” in part as a victory for their side, in reality, it’s not. There is a gag order back in place and if Trump continues his tirades, there will be consequences.

The opinion is 68 pages long and there’s a lot in it. Here’s the meat of what the court held:

That’s the top note here and if you’ve read this far, you know the most important parts. But if you have time for a deeper dive, the opinion is a fascinating one. We learn a lot about how Trump’s lawyers handle matters when the law isn’t on their side and how much important information judges can convey in the low key language they are wont to use. So, no need to read on, because this is the technical legal part and this piece is about triple the size of what I usually try to give you, but here we go, in case you have an appetite for more. Settle in for reading this, perhaps at more than one go, and better yet with a glass of wine or eggnog in hand if you’ve got it.

Judge Chutkan’s original gag order provided: “All interested parties in this matter, including the parties and their counsel, are prohibited from making any public statements, or directing others to make any public statements, that target (1) the Special Counsel prosecuting this case or his staff; (2) defense counsel or their staff; (3) any of this court’s staff or other supporting personnel; or (4) any reasonably foreseeable witness or the substance of their testimony.” And the Judge explicitly said that it wasn’t to be construed as prohibiting Trump from making statements that are critical of the “government generally” including DOJ, that maintain Trump is innocent and that his prosecution is politically motivated, and that criticize political rivals, which at the time included his vice president Mike Pence, who has since withdrawn from the Republican primary race.

The court of appeals decided Judge Chutkan’s gag order could be drawn more narrowly to maximize free speech while protecting the integrity of the criminal justice process. They wrote, “The district court’s ban on speech that “targets” witnesses and trial personnel reaches too far” because it would prevent Trump from calling former government officials or potential witnesses liars or calling special counsel Jack Smith a “Trump hater.” The court thinks doing those things is okay, and objects to Judge Chutkans order because “permitting Mr. Trump to answer … political attacks with only an anodyne ‘I beg to differ’ would unfairly skew the political debate while not materially enhancing the court’s fundamental ability to conduct the trial.”

So, the court wants to narrow the gag order so that it only prevents Trump from making comments about people who may be witnesses only insofar as they relate to their testimony, leaving him free to characterize them as scoundrels, criticize their governing style, or talk about what they’ve written in their books, all of which the court concludes is essential to protect core political speech. That position makes sense. The panel judges are requiring a nexus between Trump’s speech and potential witnesses’ trial testimony to protect free discussion by Trump beyond that as well as “the fair and orderly administration of justice.” That is the sort of tight, narrow justification that should pass muster in the Supreme Court, at least if it doesn’t want to see criminal trials across the country opened up to disarray.

The revised order is not a free pass for Trump. The panel states: “To be clear, narrowing the Order’s reach to statements concerning reasonably foreseeable witnesses’ potential participation in the investigation or in this criminal proceeding does not require that the statements facially refer to the person’s potential status as a witness or to expected testimony. Context matters. The statement that a potential witness ‘is a liar’ might well concern that person’s testimony if made on the eve of trial or immediately following news reports that the person is cooperating with investigators. The same words might not concern that person’s status as a witness if uttered immediately after and in response to the release of that person’s book or media interview unrelated to this court proceeding.” The court explains at length what constitutes a nexus to witness status, providing helpful examples so there can be little dispute about the Judge’s ability to enforce her order when Trump violates it. Many of the comments Trump has made to this point would be covered. (Spoiler: of course there will be disputes, and he will fight tooth and nail over all of this.)

The appellate court also narrowed the gag order as it applied to court personnel and prosecutors, saying, “As for the protection of counsel and staff working on the case, the Order requires some recalibration to sufficiently accommodate free speech.” The court held that prohibiting any comments about them “goes too far,” and that Trump was entitled to go after the Judge or the Special Counsel. In fact, the panel commended Judge Chutkan for excluding herself from the gag order for this reason, reasoning that defendants should be free to criticize the system when their liberty is at stake.

But the opinion draws the line at comments by Trump about counsel and court staff when made with either the intent to materially interfere with their work or the knowledge they are highly likely to interfere. The panel judges write that this will ensure Trump has “done more than make a bad mistake.” The court acknowledges that the introduction of mens rea—the requirement that true knew of or intended interference—makes enforcement of the gag order in this regard more difficult, but the court concludes “that tradeoff is necessary here to protect against the ‘substantive evil of unfair administration of justice[,]’ while allowing as much speech as is consistent with that protective barrier.” The court goes into detail to describe the kind of language Trump could use that would violate the gag order: “words objectively threatening imminent physical harm—whether the covered person utters such words directly or speaks with the requisite knowledge or intent that such threats are highly likely to occur—are proscribed. Words inducing mass robocalling, doxing, or true threats being called into offices or the courthouse would also be proscribed.”

The end result for courthouse personnel and prosecutors is the court’s admonition that “working in the criminal justice sphere fairly requires some thick skin.” In other words, these folks need to be prepared to take one for the team in order to protect Trump’s free speech rights, but any sort of threat can be readily dealt with. It’s not the soul-satisfying result we may have wanted, but it is one designed to withstand scrutiny at the next level of appeal. By tightening up the order, the appellate court makes it far more likely to pass muster before the Supreme Court.

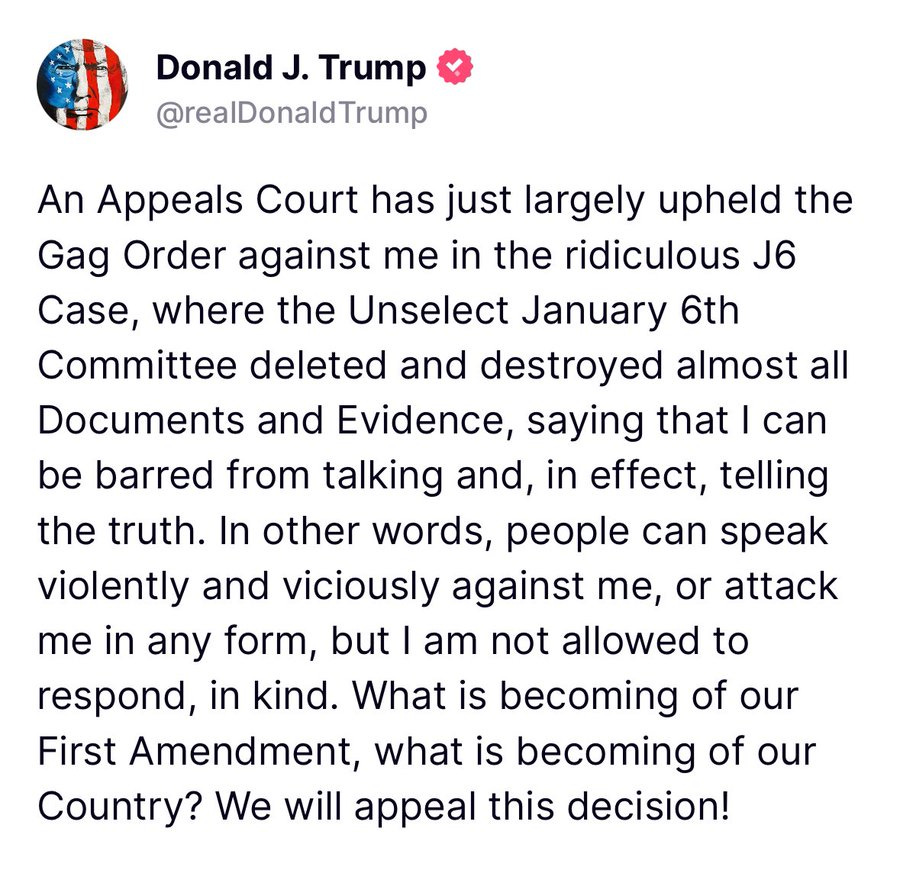

Trump himself was quick to acknowledge the order on Truth Social. This is another illustration of the value of the conventional wisdom that criminal defendants should keep their mouths shut in public, because it’s evidence Trump understands what he can’t do. That will make Judge Chutkan’s job easier if he violates it—there will be no question about whether he understood his obligations.

We’re going to get geeky for a minute and talk about the standard of review on appeal. The standard of review is the measuring stick appellate courts use to decide whether the court below got it right. It’s easy to understand how they can be outcome determinative by comparing them to a more familiar concept: burdens of proof at trial. We know that it’s easier for a plaintiff to win a civil case, where the burden of proof is a preponderance of the evidence (claims are “more likely than not” true), than it is for the government to prevail in a criminal trial, where they must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Standards matter.

Here, we have the appellate court explaining the standard of review it must use for Judge Chutkan’s gag order:

The basics here are that appellate judges don’t defer to a district judge’s rulings on purely legal issues; they are equipped to decide what the law requires just as well as, perhaps better in their view, than the trial court judge. So their review of legal issues is “de novo”—anew or afresh. But when it comes to the trial judge’s factual findings, appellate courts give the great deference because trial judges hear directly from witnesses and are in a position to assess their credibility. It’s a lot like football, where officials in the box apply their own judgment about what the rules of the game are, but defer to calls made by a referee on the field who was standing 10 feet away from a play.

Once we understand the standard the court will use to evaluate Judge Chutkan’s gag order, we’re ready to look at how they frame the issue. They write that the case involves the intersection of “two foundational constitutional values … the right to free speech and the fair and effective functioning of the criminal trial process.” The court’s job is to balance them.

Importantly, the court notes in this context that Trump’s right to a fair trial doesn’t permit him to insist on what they refer to as “the opposite of that right” because the public, too, has a compelling interest in “fair trials designed to end in fair judgments.” And while acknowledging that restraints on free speech about ongoing criminal proceedings are presumptively unconstitutional and can only be imposed if they are narrowly tailored to address serious threats, in a case involving extensive media coverage and public interest, the court “cannot sit back and wait for a ‘carnival atmosphere’ to descend before acting.”

And so, they decide that Judge Chutkan “had the authority to restrain those aspects of Mr. Trump’s speech that present a significant and imminent risk to the fair and orderly administration of justice, and that no less restrictive alternative would adequately address that risk.” Where they depart company from her is their conclusion that her order isn’t narrowly tailored enough to comply with the Constitution. That’s the reason they only affirm “in part”—they narrow the gag order to better balance the respective legal rights in issue.

The paragraph above summarizes the three steps in the legal test used to evaluate a gag order: is there a problem that the court has the authority to address, are there any less restrictive measures the court could use, and is the solution the court comes up with as narrowly tailored as possible to address the problem. Assuming Trump follows up on his promise to appeal to the Supreme Court, the justices, if they decide to take the case, (or even if they don’t, determining that the court of appeals ruling should stand), will use that same legal format to evaluate whether the lower court got the answers right.

A couple of points of note:

The Legal Arguments

The court rejected Trump’s argument that his speech can’t be restricted in any way for three reasons. First, because it ignores “the need to protect the criminal justice process.” Third, because Trump “fails to account for the difference between trial participants and nonparticipants.” In other words, because he’s the defendant in a criminal case, the court has more latitude to restrict his speech.

The second reason is more detailed, and it’s worth unpacking.

The court says Trump gets the legal standard for evaluating his free speech rights wrong. This is one of a number of places where the panel concludes Trump’s lawyers don’t correctly state the law, and although they are not explicitly critical of them, limiting themselves to comment as they do here, that they got it “wrong,” there is an undeniable impact to seeing the repetition of the criticism—the former president of the United States has a legal team that is either inept or that understands that Trump loses if the correct legal standard is employed, so they resort to using the wrong legal standard. Either way, a bad look for Trump.

Here, Trump argued that his speech couldn’t be restricted unless he presented “a clear and present danger.” The court rejects that as the standard, pointing to cases where the Supreme Court “explicitly” rejected it in favor of asking “whether any compelling interest justifies an appropriately limited speech restriction.” The court noted that Trump’s lawyers “refused” to make any argument about weighing those interests as the Supreme Court has directed lawyers to, insisting that “clear and present danger” is the only test that the court can apply and “that it categorically prohibits any speech-limiting order in this case.” The court recites the facts and rejects Trump’s argument. Trump was always going to lose here, because he failed to make any argument, let alone one that would permit him to prevail, under the correct standard.

It’s worth nothing that this isn’t how any lawyer worth his or her salt argues cases. As we discussed the other night in the context of Jack Smith’s 404(b) notice about the use of evidence of other crimes and bad acts, lawyers like to have multiple reasons that their position is correct in play. You’d expect Trump’s lawyers to argue for the clear and present danger standard they prefer, but to also argue that they win if the standard is the interest-weighing test the government argued for before both the district court and the appellate court—especially since there is a prior Supreme Court decision that makes clear it’s the correct one. The failure to do so is tantamount to an acknowledgement that Trump loses. And it’s very telling to legal insiders that Trump’s team doesn’t have a legal leg to stand on here.

Beyond that, it’s worth noting that the legal standard Trump insists on flunks the common sense test. No other defendant in a criminal case can or should be able to get away with what he has been doing. Even though the arguments are all dressed up in legalize, it’s always been clear Trump can’t do or say whatever he wants here, and his lawyers’ failure to acknowledge that really influences the court’s assessment of his arguments.

So that’s the legal part of the opinion. After reviewing it, we know that the court believes it should decide whether the gag order is justified, other options are absent, and it as narrowly tailored as possible. The court does not believe the First Amendment prevents its imposition.

The Facts

The court then turns to the facts, concluding, “The record before the district court and its factual findings demonstrate that some of Mr. Trump’s speech poses a significant and imminent threat to the fair and orderly adjudication of the criminal proceeding against him.” This means Trump is going to lose, at least in part, and that, of course, is precisely what happens.

But before we leave that sentence, note that it’s pretty astonishing. Take a moment. A federal appellate court has found that the former president and leading candidate for the Republican nomination “poses a significant and imminent threat” to a court proceeding—not just any proceeding, but one where he is on trial for trying to steal an election. That’s a big moment. But it’s the only conclusion possible on these facts, which the court goes on to review.

The first example the court points to is one we all remember, Trump’s stark threat the day after his initial appearance, “IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I’M COMING AFTER YOU!” The opinion goes on to review Trump’s many attacks on witnesses and court personnel, including his attacks on Judge Engoron’s law clerk in the New York civil fraud case and the comments about Fulton County, Georgia, election workers Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss that turned their lives “upside down.”

All of this is fair game for the appellate court to consider. It can do that because the government offered evidence of them in the proceedings before Judge Chutkan—they are part of the record on appeal. The appellate court can only consider facts and legal arguments that are included in that record, with extremely limited exceptions.

They also take note of evidence of Trump’s own assessment of the impact his words have on his followers, that the government offered. The are Trump’s comments during a CNN town hall where Trump “recognizes the power of his words and their effect on his audience,” and agreed “that his supporters ‘listen to [him] like no one else.’” Oops.

After reviewing the facts in the record, the court reaches its conclusion. Remember, we started by noting that the court reviews issues of law without deference to the trial judge’s conclusions—“de novo” review. But when it comes to the facts, we see the very deferential review used to assess the trial judge’s conclusions: “Based on that record, the district court made a factual finding that, ‘when Defendant has publicly attacked individuals, including on matters related to this case, those individuals are consequently threatened and harassed.’ … Mr. Trump has not shown that factual finding to be clearly erroneous, and we hold that the record amply supports it.”

The Ruling

Now we’re on to the ruling. The court starts by noting that Trump couldn’t say many of the things he said on social media directly to one of the witnesses—that would have been intimidation or obstruction—“the district court’s prohibition on Mr. Trump’s direct communications with known witnesses would mean little if he can evade it by making the same statements to a crowd, knowing or expecting that a witness will get the message.” The court concludes that, “the district court had the authority to prevent Mr. Trump from laundering communications concerning witnesses and addressing their potential trial participation through social media postings or other public comments.”

The court also points out something that prosecutors know to be true. If a defendant threatens one witness, it has a spillover effect on others. The court details the problem at length, noting: “hostile messages regarding evidentiary cooperation that are publicly relayed to high-profile witnesses have a significant likelihood of deterring, chilling, or altering the involvement of other witnesses in the case as well. The undertow generated by such statements does not stop with the named individual. It is also highly likely to influence other witnesses. Even witnesses not yet publicly identified, who lack the special capacity or resources to protect themselves or their families against the risk of ensuing threats or harm, will be put in fear.”

The panel writes that the courts have an obligation to keep this from happening. It agrees with Judge Chutkan that this applies both to witnesses and court personnel/prosecutors, who should not be subject to “outside pressures.” It concludes with this remarkable pronouncement about a former president, “Just as a court is duty-bound to prevent a trial from devolving into a carnival … so too can it prevent trial participants and staff from having to operate under siege.” Operating under siege because of the repeated attacks a former president has directed at them!

We’ve spent a lot of time over the last few weeks here at Civil Discourse talking about how Trump intends to rip the guts out of the rule of law and American-style democracy if he wins a second term. Here, we have three judges, using the quiet, understated language of the courts, saying Trump’s efforts in that regard are already well underway. The gag order is justified because the courts have to protect themselves from the siege he’s laid.

Next, the court easily rejects Trump’s remaining objections to any regulation of his speech.

Trump claims harm has to occur before the courts can restrict him. The panel points out that not only has SCOTUS said otherwise, but that it makes no sense to give a defendant like Trump “one free bite” at harming the process or someone involved in it before he can be held to account.

Trump says he can’t be held responsible for what his followers do after listening to him. The court says the danger of Trump’s followers acting out following his words “is magnified by the predictable torrent of threats of retribution and violence that the district court found follows when Mr. Trump speaks out forcefully against individuals in connection with this case and the 2020 election aftermath on which the indictment focuses.” They go on to say, “The First Amendment does not afford trial participants, including defendants, free rein to use their knowledge or position within the trial as a tool for encumbering the judicial process.” The panel notes that if Trump has concerns about the impartiality of court personnel or prosecutors, his lawyers can and should file an appropriate motion.

“Third, Mr. Trump asserts that, because he is running for office, the trial is at issue in the campaign, meaning his comments about the trial are political speech that cannot be regulated without the strictest showing of necessity,” the panel states. The court acknowledges that political speech is entitled to robust protection. But it says: “The existence of a political campaign or political speech does not alter the court’s historical commitment or obligation to ensure the fair administration of justice in criminal cases. … Mr. Trump acknowledges as much by accepting his pretrial release condition that he cannot speak to witnesses in the case about political matters or otherwise. He cannot evade that legitimate limitation by dressing up messages to witnesses in political-speech garb.”

So we reach the court’s core conclusion: “For the reasons outlined above, this record establishes the imminence and magnitude, as well as the high likelihood, of harm to the court’s core duty to ensure the fair and orderly conduct of a criminal trial and its truth-finding function. That significant and imminent threat to the core functioning of the judicial branch reflected in this record constitutes a compelling interest … On the record before us, that compelling interest establishes a sufficient predicate for the district court to have imposed some limitation on trial participants’ speech. The constitutional solicitude for political speech remains, though, and requires that less restrictive alternatives not be viable and that the scope of the order be narrowly tailored.”

The court concludes no less restrictive measure could meet the need, and that Judge Chutkan had already tried something less restrictive, noting that, “Shortly after the indictment, she cautioned the parties and counsel against speech that would prejudice the trial process and sought their voluntary compliance.” That didn’t work with Trump.

And most interestingly, the court resoundingly rejects Trump’s suggestion that the trial should be delayed until after the election to avoid these problems, writing, “delaying the trial date until after the election, as Mr. Trump proposes, would be counterproductive, create perverse incentives, and unreasonably burden the judicial process. Allowing prejudicial statements to go unchecked for an even longer pre-trial period would simply compound the problem.” And it points out that, “A criminal defendant cannot use significantly and imminently harmful speech to override the district court’s control and management of the trial schedule. Delays also “entail serious costs to the [judicial] system,”

One final detail. The court seems to think Judge Chutkan made a mistake by not including jury intimidation as a basis for her order, and in footnote 18, they say:

This is, of course, an invitation for her to extend the gag order to protect potential jurors, once jury selection gets underway. The Judge has scheduled that process to begin on February 9, 2024.

Will Judge Chutkan’s March trial date hold up in light of this ruling and the appeal of her orders denying Trump presidential immunity and ruling against him on double jeopardy? This panel thinks so. Midway through the opinion, on page 48, the court is discussing one of Trump’s suggestions—that the gag order should be suspended in the months leading up to the election. The court writes, “that proposal is not remotely viable.” And then comments in a very offhand manner, “in this case, the general election is almost a year away, and will long postdate the trial in this case.” Suspending the gag order ahead of the election will not be necessary the judges say—the trial will be over long before the election takes place. There are no qualifications, they present it as a statement of fact.

Of course, this is just one panel consisting of three of the judges on a larger court of appeals, and the Supreme Court will have the final say on this matter, either by taking up the case or refusing to do so, with that Court controlling much of the timing. But this is still a consequential comment for the panel to make, setting their expectation for how the courts will handle these matters.

Four Justices must vote for the Supreme Court to hear a case. Clarence Thomas should not participate in anything concerning Trump, given his well known conflicts, but no word yet on whether his recusal in the John Eastman matter was a standalone because Eastman is one of his former law clerks or if it signals a shift in Justice Thomas’ views on his need to recuse. If he participates, so much for the public’s confidence in the integrity of the Roberts Court, which is already at low ebb. But even so, in addition to Justice Alito, Thomas would still need two more votes to hear the matter. Justice Gorsuch might climb on board, but if Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh hope to break free of the country’s impression that they were put on the court to do Trump’s bidding and that they remain his caged animals, they might well decide to let the appellate court’s decision stand—especially since there is clear Supreme Court case law setting out the legal standard, the appellate court has “fixed” the gag order to comply with it, and the district court’s decisions about the facts are entitled to deference. Some issues regarding Trump are novel and demand the high court’s attention. But this one is not.

If the Supreme Court does leave the appellate court’s opinion in place, that would still leave the matter of how quickly the courts are prepared to act. We know they can move quickly when they are of a mind to—the Eleventh Circuit showed us that when they handled the Aileen Cannon appeal, and the Supreme Court moved quickly during Watergate. The bottom line is that Trump has a March trial date in the District of Columbia, and the courts should make sure he gets there on time.

The court of appeal’s opinion is understated when it comes to Trump’s transgressions. The judges do not scream and shout or engage in rhetorical snark. But their opinion nonetheless makes a compelling argument for keeping him out of the public arena, and certainly out of the White House. Unfortunately, at 68 pages, it’s too long of a read for the folks who would benefit the most from it. But it is finely tuned for the coming appeal to the Supreme Court. If Trump loses there, it would be a resounding defeat, and perhaps the courts’ message, that Trump threatens their ability to conduct a fair trial because of his threats and bullying, might break through.

The appellate court stuck to its guns. Let’s hope the remainder of their brethren and sistren do too. The panel’s conclusion is this: “Mr. Trump is a former President and current candidate for the presidency, and there is a strong public interest in what he has to say. But Mr. Trump is also an indicted criminal defendant, and he must stand trial in a courtroom under the same procedures that govern all other criminal defendants. That is what the rule of law means.”

Thanks for sticking with me—I know this has been beyond lengthy.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Wowzer! My head is exploding and I actually am stunned at all the intricacies. But if all this parsing and weaving and clarifying and tailoring and adapting and fine tuning get the man to SHUT UP at all, then it’s worth it.

You may have said it was long and deep but that's exactly what we appreciate the most. It's a chance for us to understand the complexities of the case and for us to more fully appreciate the 'system' as a whole. Thanks SO much and keep it coming. It's best when the electorate is informed and you're doing just that. We're most thankful.