Monday night, we got the first reports that something might be happening in Florida—a grand jury was meeting there on a matter related to Trump and the documents. That wasn’t the big news everyone was geared up for, with most of the media on Trump indictment watch in Washington, D.C. But by Tuesday morning, members of the media were hightailing it to the federal courthouse in Miami in search of the proceedings. There are two other courthouses in the district, notably one in the West Palm Beach division where Mar-a-Lago is located, that have space designated for a grand jury.

I’m told the courthouses were locked down tight and it was difficult for members of the media to discern much beyond the fact that that grand jury would be meeting this week. They didn’t learn much, if anything, about what was going on and who might be testifying. This is unsurprising as federal courts know how to impose a strict lockdown on grand juries—they are supervised by the courts, not prosecutors. And many federal courthouses have what’s known as “sally ports,” secure points of entry into the basement or parking deck attached to the courthouse that witnesses can be brought through privately, by prior arrangement with the U.S. Marshal, and then sent quietly up to the grand jury room.

We’ll have to wait to learn precisely what this means. Could it be a proceeding for the convenience of witnesses for whom travel to the District of Columbia is problematic? Could it be that Trump is being indicted in Florida, not Washington, D.C.? While both are possible, it’s more likely that some folks who were involved in obstructing the investigation in Florida, but not in any conduct that took place in Washington, are being investigated by a Miami grand jury and that prosecutors hope to charge and perhaps flip them as a result of an investigation being conducted there.

That possibility makes it a good idea for us to take a brief detour and talk about venue. Venue, as a legal proposition, is the place or location where conduct that prosecutors want to charge took place—the judicial district where the crime was committed. Sometimes that’s obvious, like in a bank robbery. Other times, it can be more difficult to determine, and there may be more than one possible venue. Imagine a drug-dealing network that operates across a region of the country. There can be more than one proper venue for a case.

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 18 provides that “Unless a statute or these rules permit otherwise, the government must prosecute an offense in a district where the offense was committed. The court must set the place of trial within the district with due regard for the convenience of the defendant, any victim, and the witnesses, and the prompt administration of justice.” There are 94 judicial districts across the country. The District of Columbia is one of them. The Southern District of Florida is another. Although many districts are further broken down into divisions (that’s the whole issue we saw, both with medication abortion in Texas and with Trump’s filing of a challenge to the search of Mar-a-Lago in the West Palm Beach division in Florida, to get a favorable judge when there is only one judge hearing cases in a division), they aren’t relevant to a venue analysis.

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution and the Sixth Amendment give a defendant the right to be tried in a forum where the crime was committed. A defendant can waive venue, but absent a waiver, the government’s case fails if it doesn’t prove venue at trial by a preponderance of the evidence. It’s a serious matter. There are cases where convictions have been reversed on appeal because the government picked the wrong venue. In one such case involving computer crimes, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals clarified the importance of venue, holding that “Venue in criminal cases is more than a technicality; it involves ‘matters that touch closely the fair administration of criminal justice and public confidence in it.’” The bottom line is that the consequences of getting venue wrong are dire.

If prosecutors have developed concerns that there are either some charges or some defendants for whom venue is only proper in Florida, that could explain the separate grand jury there. For instance, since most of the obstruction occurred in Florida, prosecutors may have determined that the crime must be charged there, or it could be something that isn’t yet public. Reporting suggests that the grand jury in Florida only began meeting last month and has heard from a limited number of witness, which may support the idea that this could be an investigation involving an individual whose conduct occurred solely in Florida and whom the government hopes to charge and flip. But it’s also possible to charge one defendant in two locations. Special counsel Robert Mueller charged Paul Manafort in the District of Columbia and the Eastern District of Virginia. While separating charges introduces some complexity into the matter, ensuring any convictions can be affirmed on appeal absent concerns about venue takes precedence.

It’s worth understanding because even if venue doesn’t explain this second grand jury, it’s likely to be one of the defenses Trump will try if indicted. Stay tuned.

A new and interesting detail emerged Tuesday in the January 6 investigation in Washington. The grand jury there has heard testimony from around 20 members of the former president’s Secret Service detail.

What are investigators looking for? In most criminal cases, you don’t have a defendant who is under 24/7 security surveillance like a former president is. It’s a treasure trove for prosecutors. As relates to the documents case, prosecutors might want to learn more about the former president’s activities and movements around the time DOJ showed up at Mar-a-Lago to collect classified material and boxes that were reportedly removed from storage by Trump employees so he could have the opportunity to review them, before they were returned to storage. Prosecutors might want to ask agents whether they observed Trump showing classified documents to anyone. Establishing that Trump actually disseminated classified material would implicate additional and extremely serious crimes. Secret Service agents may be able, for instance, to shed light on Trump’s meeting with Mark Meadows’ biographers and the notorious rustling of papers when Trump referenced a classified document about invading Iran.

Secret Service agents are always with Trump. And they are also highly trained as observers and witnesses. After initial training at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia, (where I received training on explosives and arson) newly minted agents have some advanced training and then typically spend three to five years assigned to a field office where they work on financial crimes cases within the Secret Service’s jurisdiction, along with protection detail duties. Agents work criminal cases and testify before grand juries and trial juries. It’s their job. In other words, these folks are trained witnesses. As a prosecutor, you couldn’t ask for much better.

Finally, news that former Trump Chief of Staff Mark Meadows has testified before the special counsel’s grand jury also surfaced Tuesday. On May 21, in The Week Ahead edition of the newsletter, I wondered where he’d been hiding after the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered him, in early April, to testify before the grand jury. I looked but wasn’t able to find anything that confirmed he had testified or that a date had even been scheduled.

Late Tuesday, we learned Meadows has testified, on both the January 6 case and the documents case. Meadows, if cooperative, could be a key witness in both. It was his cache of texts that paved the way for the January 6 committee’s remarkable success. He had unique access to Trump in the run-up to and aftermath of the election and may know whether Trump believed he’d been the victim of fraud and hadn’t really lost the election—he may have been involved in conversations or overheard ones that show Trump understood the truth and proceeded with the Big Lie anyway. He was with Trump throughout the insurrection. And so much more. Everyone communicated with Meadows.

As chief of staff, he was also involved in packing up Trump’s office when he left the White House and was one of his representatives to the National Archives. He could play an important role in the documents case, too. Here’s to hoping that Meadows’ time with the grand jury was lengthy, because there is a lot of important information to elicit from him.

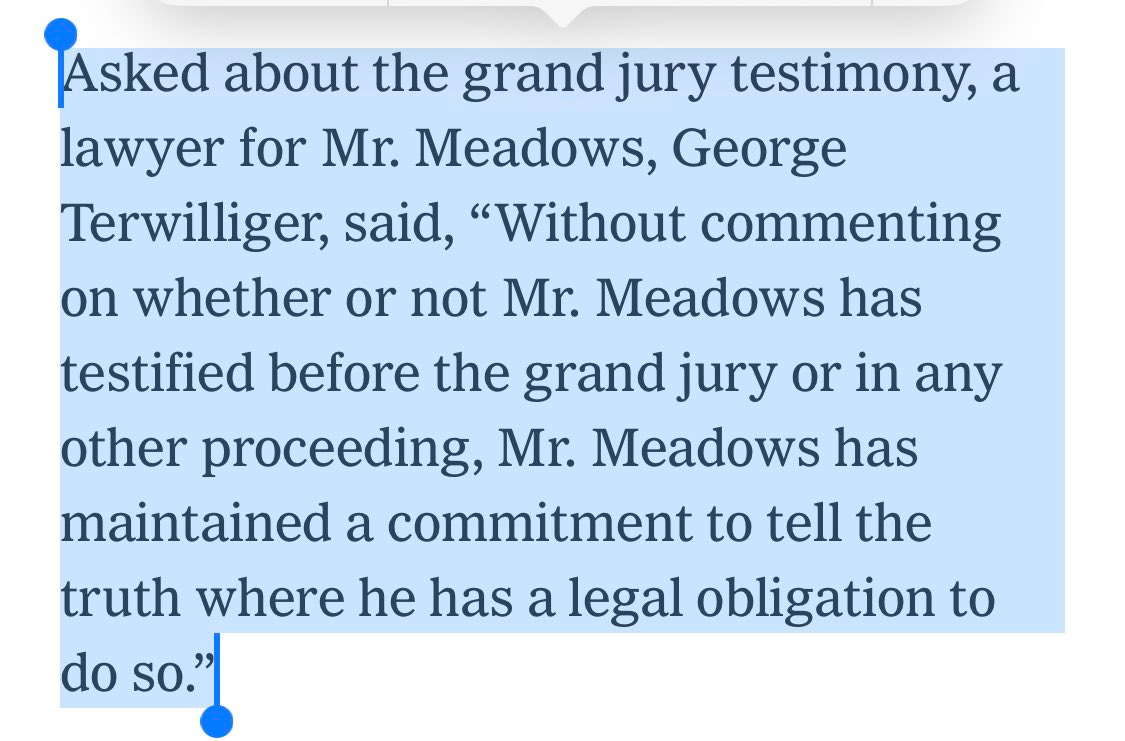

Meadows’ lawyer, George Terwilliger, declined to confirm his client had testified but said he’d tell the truth when he had a “legal obligation” to do so. Sort of a pathetically low bar for a former public servant who was willing to write a book but not to prevent an insurrection. But that statement, combined with the fact that Meadows’ testimony was apparently kept secret from the Trump camp, can’t help but raise speculation that Meadows is cooperating with the government. His lawyer’s statement seems to rule out voluntary cooperation, done because it’s the right thing to do. That leaves a couple of options. First, if prosecutors were prepared to charge Meadows, he could have reached a deal with them that requires him to plead guilty and to cooperate, in exchange for a reduced sentence. Even if prosecutors decided against charging Meadows, given his adjacency to the Big Lie it seems unlikely that any knowledgeable lawyer (and Terwilliger is a former Deputy Attorney General from the George H.W. Bush administration) would let him testify without some guarantee. That would most likely come in the form of an immunity order that would free Meadows from the threat of prosecution but also extinguish any Fifth Amendment right he had to avoid testifying.

All in all, it’s been a very bad week for Trump so far, and we’ve only just finished up Tuesday. Today, Wednesday, June 7, is the anniversary date for Civil Discourse. We’re one today! Wouldn’t it be great if today was The Day? Whether it is or not, we’re certainly going to have an interesting second year. I hope you’ll stick around!

We’re in this together,

Joyce

"Today, Wednesday, June 7, is the anniversary date for Civil Discourse. We’re one today! Wouldn’t it be great if today was The Day? "

~ Here's hoping it a happy birthday for all of us!

Who better than a former prosecutor to analyze the crumbs of information falling from the plates of the DOJ, the courts and multiple reporters with their multiple sources and constructing most plausible explanations for what appears to be happening. We are the anxious public who want to know yesterday what is happening today in the halls of justice. We seem to have a voracious appetite for this justice, after being used and abused as vassals by an elected official who should have behaved as a public servant rather than an emperor. Why this particular official above all others? Because he slithered his way to the pinnacle of our political and governmental system, while behaving childishly, boorishly, proudly and shamelessly, flaunting his power over others as well as his power to scandalize and outrage the public. We desperately want and need to know that the right will prevail.