I’ve been nursing a sick baby chicken, Cleo. We rescued her from a hawk earlier this week, only because my sharp-eyed son, who was helping me with a 50-lb. sack of chicken feed down to the shed, realized what was going on. Raising helpful children definitely has its rewards.

Cleo has been inside with me ever since, and I have to tell you, it was touch and go. The first night, she was still in shock and slept on top of me (and yes, for those of you who are curious, chicken diapers are a thing, but she still hadn’t had anything to eat or drink, so it turned out okay for me and our bed), while I dozed fretfully. I was grateful for the first-aid kit I bought when we first got chickens at the start of the pandemic—despite some pretty serious damage to her wing and chest area, I had all the right chicken medicines. I’m increasingly hopeful the wounds won’t get infected and she’ll heal up, although I’m not sure the feathers on the damaged wing will regrow.

All that to say, it’s been several days since I posted, for which I apologize. I don’t think I’d fully realized how much these sweet, silly chickens have come to mean to me. Cleo is out in the coop tonight, sleeping with her family to make sure she stays bonded to them, and I’m back to writing! That’s a good thing, because there’s going to be a lot going on in the week ahead.

This week there will be the start of round two of trials for members of the Oath Keepers militia group. This time, prosecutors face new hurdles. Rather than leaders like Stewart Rhodes, they will be trying some of the lower-level members and will have to convince the jury that they too joined the conspiracy to commit sedition. It’s likely that these defendants will argue they were simply swept up in events on January 6, 2021, without ever agreeing with Rhodes and others to use force to interfere with the certification of the Electoral College vote.

My Obama administration colleague from Idaho, former U.S. Attorney Wendy Olson, had a very solid take on the convictions in the first Oath Keepers trial. She texted me, “That is a big win, in part because losing it would have been a big loss.” If DOJ hadn’t been able to convict, it would have become still more difficult to convince the decision makers at DOJ to risk indicting Trump. Ultimately, the absence of a loss in the Stewart Rhodes case may be more compelling than the fact that there was a conviction. It makes the possibility of indicting Trump, not just for Mar-a-Lago but also for January 6, more real, though still far from certain.

On Tuesday, prosecutors in federal court in the District of Columbia will begin jury selection for the next Oath Keepers trial, which is expected to last five to seven weeks. The defendants face additional charges, including conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding, obstruction of an official proceeding, and conspiracy to prevent an officer from discharge of his duties. It may take a little time to find a jury that does not have preconceived notions about this case, given how close in time this it is taking place to the prior one. Defense lawyers are sure to screen carefully to see if potential jurors saw any coverage of the first trial, which might lead them to assume conviction is merited. But not only are jury pools far less on top of current events than lawyers tend to think they are, anyone who followed the coverage in the earlier case is likely to know that only two defendants were convicted of seditious conspiracy, while others were acquitted. We may hear considerable commotion from the defense during jury selection, but it’s likely there will be a jury in the box by the end of the week, barring unusual developments.

And there’s more to come. On December 19, DOJ will try Enrique Tarrio and other members of the Proud Boys on seditious conspiracy charges. Tarrio was arrested and charged in March 2022, but it wasn’t until the Justice Department filed a second superseding indictment on June 6 that the seditious conspiracy was added. You can read the full superseding indictment here; it has a lot of fascinating detail.

DOJ characterizes the Proud Boys and the case against them this way:

the “Proud Boys describe themselves as members of a ‘pro-Western fraternal organization for men who refuse to apologize for creating the modern world, aka Western Chauvinists.’ Through at least Jan. 6, 2021, Tarrio was the national chairman of the organization. In mid-December of 2020, Tarrio created a special chapter of the Proud Boys known as the ‘Ministry of Self Defense.’ As alleged in the indictment, from in or around December 2020, Tarrio and his co-defendants, all of whom were leaders or members of the Ministry of Self Defense, conspired to prevent, hinder and delay the certification of the Electoral College vote, and to oppose by force the authority of the government of the United States. On Jan. 6, 2021, the defendants directed, mobilized and led members of the crowd onto the Capitol grounds and into the Capitol, leading to dismantling of metal barricades, destruction of property, breaching of the Capitol building, and assaults on law enforcement. During and after the attack, Tarrio and his co-defendants claimed credit for what had happened on social media and in an encrypted chat room.”

Keep in mind that the Proud Boys provided security for both Roger Stone and Alex Jones at various points in time. One of their number, Jeremy Bertino, pled guilty earlier this year to seditious conspiracy charges and agreed to cooperate with the government. Having an insider cooperating is the icing on the cake to the evidence, which, if it comes in as neatly as it is laid out in the indictment is compelling. The Proud Boys defendants—especially after convictions in the Oath Keepers trial, in which every defendant was convicted of a 20-year felony if not of seditious conspiracy—would be smart to look for deals. Of course, people in Trumpworld don’t seem to do that. Perhaps they believe the appeals process can drag out long enough for them to survive to get a pardon from Trump in the future. But that’s quite a gamble.

That’s why this prosecution could be a turning point. Although it will be handled by the U.S. Attorney’s office in the District of Columbia, any defendants who become cooperators as a result would likely benefit the special counsel’s investigation into Trump’s inner circle. DOJ’s seemingly elusive effort to find witnesses who can help them better understand what was going on in the Willard war rooms could be significantly aided if, in classic investigative fashion, defendants here cooperate against folks like Roger Stone, helping DOJ build cases and continue to work up the chain to get to the most culpable people. To do that, there are usually stages in the investigation as the evidence against the top people is built out. There has always been reason for conjecture that Stone, who remained in direct contact with Trump over the years, would be a productive cooperator if he ever decided to become one. And, it would be unsurprising to see the special counsel, if he decides to move forward on charges related to January 6, do it in stages designed to develop additional evidence before making a decision about Trump himself. The Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers could be the jumping-off point.

A last point on these trials. There’s usually a delay of several months between conviction and sentencing in federal cases. Among other, more pedestrian reasons, like finding time on a federal judge’s calendar, it takes time for a federal probation officer to write the presentence report that collects all of the facts the judge will need to determine the correct sentence and work up an estimated calculation of a defendant’s sentencing guidelines range, which is the starting point for the judge’s consideration. It’s possible to do some educated guesswork about the sentence Rhodes is facing, and understanding what that looks like can be a persuasive part of current and future defendants’ assessments of whether to cooperate or not. A person who might think they can spend two years in prison might make a different decision if they’re facing 15 or 20 years.

For instance, Roger Stone was notoriously vocal about his reluctance to serve time. After Trump criticized the government’s recommendation of seven to nine years in custody, then-Attorney General Bill Barr got involved, submitting a revised filing that, while not requesting a specific sentence, suggested the government’s earlier recommendation had been too high. Trump ultimately commuted Stone’s three-year plus sentence, and he never served a day of it. Sentencing computations strongly impact plea and cooperation deals, especially when you take a self-dealing president parceling out pardons out of the equation.

What will Rhodes’s sentence look like? Seditious conspiracy carries a 20-year statutory maximum sentence, but the sentences imposed in federal cases are typically lower than the maximum the statute sets. Federal judges start by calculating a range of months within which a defendant should be sentenced to, called the sentencing range. Those ranges are set forth in the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which create a calculus for sentencing based on a defendant’s conduct and prior criminal history. The guidelines take into account very specific aspects of a defendants conduct during the crime that let judges calibrate the sentence, according to how serious a defendant’s conduct was. Although the guidelines aren’t binding, they are used as the starting point for sentencing, and judges often stay within their confines.

The starting point for calculating the guideline range is a “base offense level” that is set based on the specific crime the defendant has committed. The guideline manual will tell judges (I’m making this up just to illustrate the point) that if the crime is murder, they should start with a base offense level of 30. But there is no specific reference for seditious conspiracy, perhaps because it’s so rarely charged. When this happens, the guidelines direct judges to find the most analogous conduct to the type of crime charged and begin the calculation there. For seditious conspiracy, that means looking at the treason guideline. There is no crime of “sedition” itself, but that’s because the goal of a seditious conspiracy is … treason.

That’s how DOJ and the legal team for Joshua James, an Oath Keeper from Alabama who previously pled guilty to seditious conspiracy, agreed the guidelines should be calculated in his case. There is no reason to believe it would be different for Rhodes. You can see in this excerpt from James’ plea agreement, which shows how the base offense level of 14 set under the treason guideline is increased to account for specific conduct like threatening or extensive planning. James ends up with a base offense level of 32.

Bear with me if all the numbers are making you jumpy, here’s how it works: once that total offense score is calculated, you take a look at sentencing table grid for offense level of 32. It gives you possible ranges of months to sentence within, based on the defendants prior criminal history. Once you have both the offense level and the prior criminal history score, it’s a simple matter of looking up the sentencing range on the grid.

If you’ve been with Civil Discourse from the beginning, this is somewhat familiar territory. We discussed how the guidelines work in more detail in this post. If not, you may want to take a look at the earlier post, and a look at the sentencing table may help, as well.

Although Rhodes has no prior criminal history, his guidelines calculation is likely no lower than a starting range of 121 to 151 months of custody and could well be far higher when additional conduct he committed on the path to January 6 is considered. The same holds true for the Proud Boys’ leaders, who are about to face trial. Sentences in the range of 10 to 15 years might convince at least some of these defendants that cooperating with the government is the better choice.

So that’s where we are with the seditious conspiracy trials to come and their possible influence on the overall January 6 investigation. Lots of balls in the air.

One last thing: we’re finally celebrating Brittney Griner’s return to American soil. My MSNBC colleague Ayman Mohyeldin wrote this incredibly thoughtful thread on Twitter, explaining why criticism of the deal that brought Griner home is misplaced. You may find his analysis helpful for discussing this situation with family members over the holidays.

But former Marine Paul Whelan is not yet home. Nor are other Americans in the custody of Russia and other foreign countries. Sunday morning on Face the Nation, former National Security Council advisor Fiona Hill related that while there was a potential deal on the table to bring home Whelan, who Russia arrested on suspicion of espionage in 2018, Trump wasn’t “particularly interested” in his plight. These issues seem to matter more to Biden, who in April secured the release of Trevor Reed, who had been in Russian custody for three years.

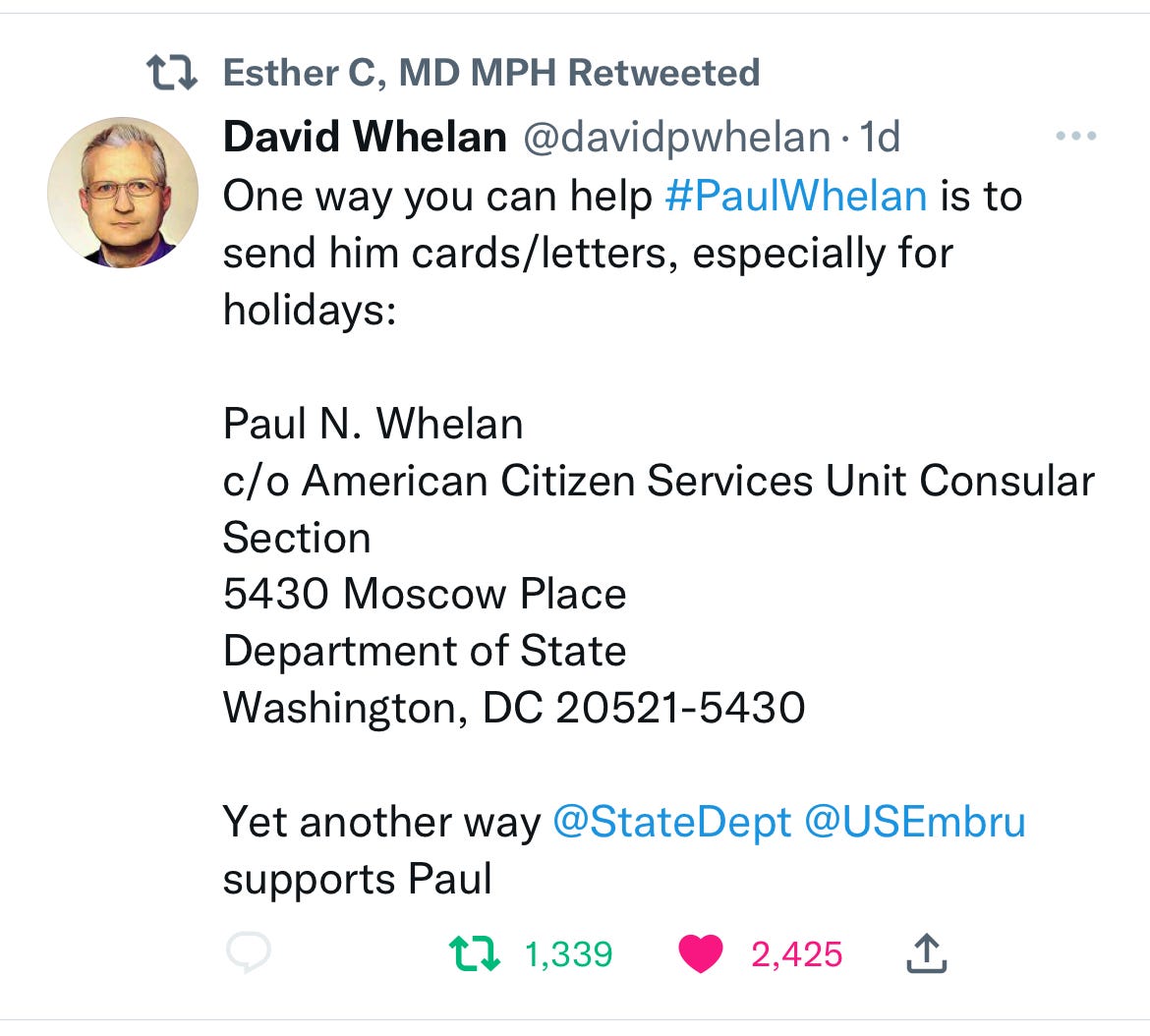

When you’re sending out your holiday cards, or even if you aren’t, consider sending one to Paul Whelan, who is spending his fifth Christmas in a Russian prison. It’s an important way to show him that he isn’t forgotten and to let the administration know there’s support for bringing him home.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

While I 100% agree we should be doing everything we can to get Whelan home, as a former member of our military, I am a bit disturbed by much of the media calling him a “retired Marine.” I note that you don’t do that, Joyce, and call him a “former Marine.” Many on the right have been asserting that, because he was a Marine, he is more “deserving” of efforts to get him home than Griner was, because she was “ungrateful” because she did not stand for the Anthem.

“Retirement” from the military has a specific meaning, and Whelan is not “retired.” He was prosecuted and convicted of a number of charges at court martial, and received a bad conduct discharge, which represents less than 0.5% of military discharges, and is one step less severe than the worst type of discharge, a dishonorable discharge, which is generally reserved for violent criminals (and is less than 0.1% of discharges). Calling Whelan “retired” is a slap in the face to those who actually earned their retirement from the military, and to those who were discharged honorably (the most common type of discharge).

I will stress again that we need to get him home. Our government is obligated to seek to gain the release of any American unjustly held in a foreign land. Whelan should be no exception, because he is an American citizen. But don’t let those on the right say that he is some sort of American military hero.

Thank you, Joyce, for your column and I hope Cleo gets better soon. 💙