The week is only just starting, but I’m already looking ahead to Thursday, when a federal judge in South Florida will hold a hearing on the rather unusual case former President Trump has brought before the court. Trump filed a request for a special master to review the documents the government seized at Mar-a-Lago (MAL). Trump also seems to be challenging the search, something that is typically reserved for a motion to suppress illegally seized evidence after criminal charges are filed against a defendant.

The Judge on this case is 41-year-old Aileen Cannon, a Trump appointed who was confirmed on November 12, 2020. In her initial filing, the Judge seemed to have some reservations about Trump’s claims. She asked his lawyers to clarify what relief they were seeking, why the court had jurisdiction, what legal standards applied and whether Trump was requesting an injunction against the government while she considered his claims. Her requests tallied with the criticism many legal analysts offered.

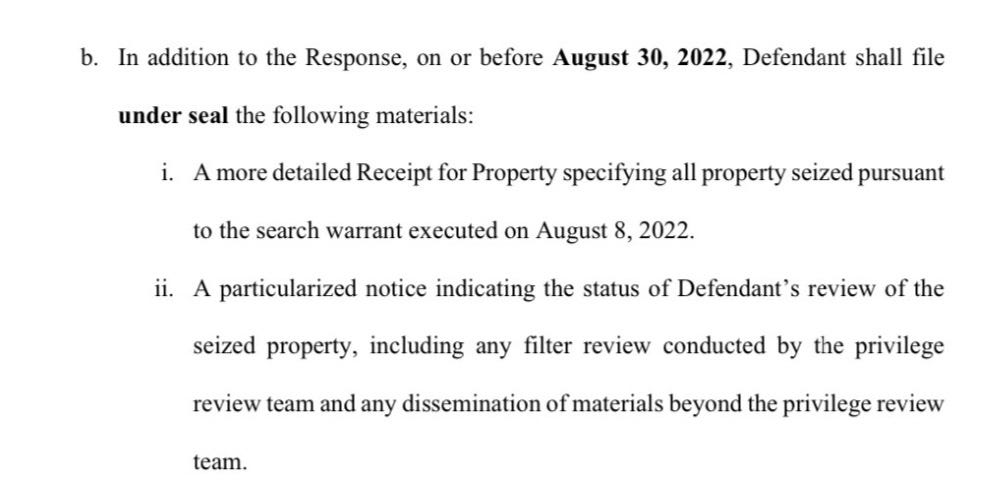

But there was a change in tone when she entered an order on Saturday, (you can read it here) declaring her “preliminary intent” to appoint a special master and directing the government to provide a more detailed list of the items it seized in the search. The detailed list could become a problem if the judge expects the government to offer precise information about highly classified material. This is a surprising ask, since the government has already filed an appropriate return of service following the search.

While the second order seems like an about face from the earlier one, I’m not compelled by the arguments some folks are making that Judge Cannon should recuse, because the former president appointed her. Every judge is appointed by a president from one party or the other. Once appointed, judges receive life tenure in large part because we expect them to adopt a position of political neutrality, making decisions based on the facts and the law. And after the 2020 election, we saw judges, including Trump appointees, do just that when called upon to rule on the outcome of the election. The former president has done far too much too damage public confidence in our democratic institutions. Let’s let this one play out before we pass judgment on the judge herself.

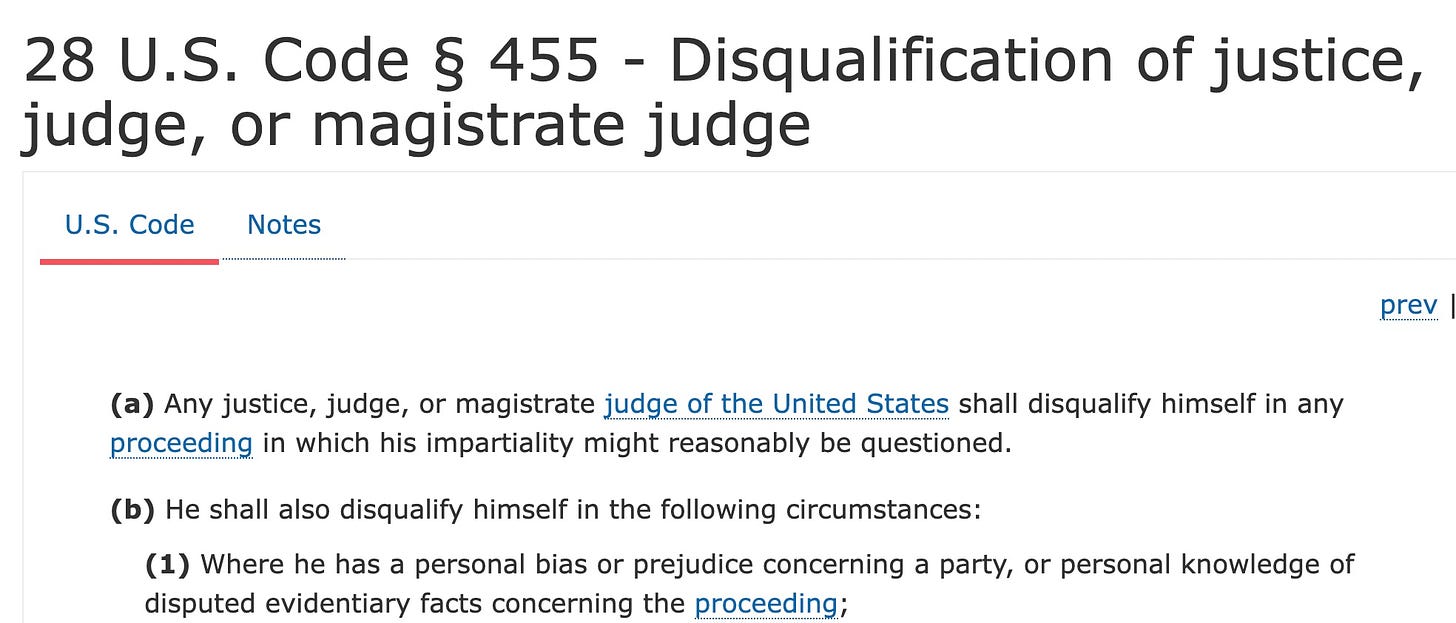

It’s worth being familiar with the law on federal judicial recusals. Here’s the pertinent part of the statute:

Judges “shall” recuse from proceedings where their impartiality could be questioned. What that means is up to judges themselves to decide. There aren’t any uniform standards and unless one of the parties files a motion requesting a recusal, the judge’s reasoning isn’t shared publicly.

We are long overdue for reform and more transparency when it comes to recusals and the federal judiciary. But here, in the absence of a motion to recuse from the government, which is unlikely, the decision about handling the case is up to the judge.

That means we’re likely headed towards a Thursday hearing in front of Judge Cannon where she will decide, among other things, whether to appoint a special master who will act as a buffer and determine whether any items seized in the MAL search are privileged items or items outside the scope of the search that need to be returned to the former president.

The whole request is a bit off. The MAL search is not the type of situation that usually gives rise to the use of a special master. We see that in cases where a search of a lawyer’s office or his electronic devices is likely to involve material covered by the attorney client privilege between that lawyer and third parties who aren’t involved in the investigation at hand as well as with the target.

In this type of situation, special masters are sometimes brought in to replace the DOJ filter teams, sometimes called a taint teams, that reviews materials seized from the target of a criminal investigation. Filter teams are made up of prosecutors or agents who are not involved in the investigation of the target. The walled-off filter teams screen seized material to make sure prosecutors involved in the prospective case don’t see attorney-client privileged material that might have been inadvertently retrieved during the search.

Here, there is no suggestion that type of privilege problem exists. Perhaps Trump got the idea from the search of one of his many lawyers—Michael Cohen, Rudy Giuliani, or John Eastman—where requests for a special master to review documents to avoid any improper access to attorney client privileged materials was a risk. To the extent Trump is arguing any documents at MAL are covered by executive privilege, that only strengthens the argument that they are presidential records that should be recovered and returned to the National Archives. Trump has offered no reason to believe the DOJ filter team that is conducting the review has done anything improper.

In 2021, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which includes Florida where this matter is proceeding, approved the use of a filter team in a case called U.S. v. Korf, over a challenge that it violated the target’s 6th Amendment right to counsel. The court wrote “Our holding on this front is not even close.”

That’s precedent Judge Cannon will need to consider, along with caselaw from other courts of appeals that have either approved the use of a filter team or declined to criticize the practice. Two Circuits, the Fourth and the Fifth have criticized the government’s use of filter teams in cases that seemed to turn more on the way those searches were handled than on the use of a team itself.

And, in a bit of judicial irony, Korf is about a search warrant for the Miami offices of a large company that government filings suggest was involved in the misappropriation of more than $100 million from a Ukrainian bank, subsequently laundering the money via domestic real estate purchases. You really can’t make this stuff up.

The issue of filter teams versus a special master aside, one of the perplexing questions in this litigation is why Trump delayed for more than two weeks before filing while DOJ likely finished or is close to finishing its review of the search materials so they can be turned over to the investigative team. If DOJ is finished by Thursday, Trump’s motion seems moot unless the judge wants to order a re-review. Something I’ll be looking for is to see whether the hearing results in unnecessary delays for DOJ, which could even require an appeal to the 11th Circuit, and of course, more delay.

Here though, the equities are on DOJ’s side. As a practical matter, DOJ seems to have returned at least one set of items that were outside the scope of the search—Trump’s passports (raising the interesting question, were his passports found in a file with classified documents?). There is no reason to believe the filter team hasn’t been equally careful with other materials that can be returned to Trump. To the extent the search resulted in retrieval of presidential papers, whether classified or not, they belong in the National Archives. Any artificial delays would only delay a meritorious investigation and bring with them the risk of greater damage to national security in the classification review Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines has said she will conduct is hamstrung.

That takes us to a key issue we lack clarity on. We don’t know if Trump is just a magpie who wanted to hang onto Kim Jong Un’s “love letters” to him or whether there was something nefarious going on. It’s easy to speculate, but if there are going to be criminal charges, DOJ must have proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Access to items retrieved from the search will be essential to moving the investigation forward and deciding about prosecution.

As we’ve discussed before, DOJ usually prosecutes cases involving retention of classified material only where there is a plus-factor that goes beyond simple retention. That could be something like destroying or damaging documents, passing them on to others who intend to publish them, or storing them in a cavalier fashion that gives guests access to them. DOJ could consider the obscenely large number of documents involved here and the repeated refusal to return them as plus factors. We don’t know if they’re inclined to do that.

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to whether DOJ is going to indict the former president. The one clear piece of information we have is that DOJ is treating this as a serious criminal matter that will require a decision on whether to prosecute before it is complete. The case isn’t over just because DOJ has now retrieved the documents.

We learned this in the legal memo DOJ filed last week. That memo accompanied the redacted search warrant Magistrate Judge Reinhart released last week. As Attorney General Garland has said repeatedly, DOJ doesn’t try its cases in the press. It speaks in court and through its pleadings. So, when DOJ files a pleading of this magnitude, it’s worth paying attention. And there it was, in the middle of a block of redacted lines of text, DOJ confirmed its active criminal investigation on pg. 7 of the motion, noting that: "[m]aximizing the Government's access to untainted facts increases its ability to make a fully-informed prosecutive decision."

Simply put, the government is working towards making a decision about whether to prosecute or not. While some pundits think prosecution is all but certain, it’s important to remember that prosecutors charged with responsibility for this case will have to engage in a careful analysis of the admissible evidence in this case (including dealing with problems that arise if classified information is too sensitive for the type of public revelation that happens when it is used at trial) and what criminal violations can be proven beyond a reasonable doubt with it. Past precedent, like the cases against Clinton advisor Sandy Berger and General Petraeus—to ensure consistency in applying the law to Trump. Like always, the outcome will turn largely on the strength of DOJ’s evidence. If DOJ learns the documents passed into other hands, then prosecution becomes an easier choice. Expect Merrick Garland’s team to pursue these issues carefully and think them out thoroughly before any charges are brought. Although prosecution seems warranted from what we see publicly, it’s always easier to be an armchair prosecutor than the real thing.

There are still more unknowns at work here: are there co-conspirators, particularly on the obstruction of justice/cover up end of things who can be charged? Is so, will any of them testify against Trump to avoid prosecution or minimize their own exposure? Could DOJ require them to disclose anything they know about the insurrection as a condition of obtaining a plea deal? Lots of unknowns as we head into the new week—stick around here at Civil Discourse (or subscribe if you haven’t already) to stay on top of them.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

You must be one heck of a teacher. I feel like I’m in a law school class I can understand. When I taught kindergarten we used to sing, we are going on a bear hunt. Next line was, We are going to catch a big one. We are in the forest, crossing the peanut butter river, Joyce has the flashlight and the crackers guiding us through. Thank you Joyce, in your special way you are helping save our country

Clearly and helpfully informative, as usual! Thank you!