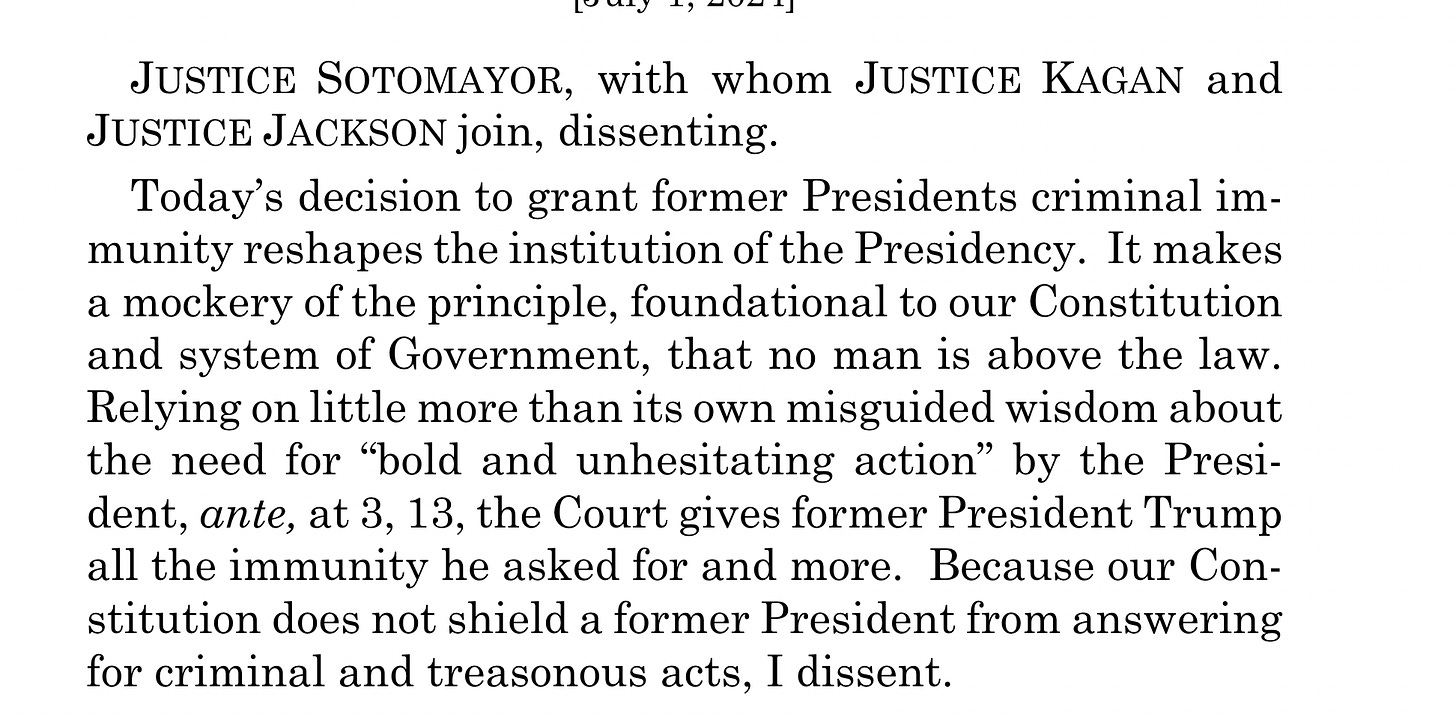

“With fear for our democracy, I dissent.” With these words, Justice Sonia Sotomayor concluded her dissent from the majority opinion in Trump v. U.S. She was joined by Justices Jackson and Kagan. She is right.

In today’s decision, the conservative majority on the Supreme Court told us in no uncertain terms who they are, and I believe them. Their decision signals that they believe it’s more important to create a powerful presidency—a long-term policy goal for conservatives—than it is to be concerned with how a president could abuse that concentrated power, including to try and overturn an election. That’s the top takeaway from today’s decision. Justice Sotomayor gets it exactly right. We should all fear for our democracy.

This is a long decision with lots of moving parts. The Chief Justice wrote the majority opinion, but Justice Thomas wrote a concurrence. So did Justice Barrett, who joined most of Justice Roberts’ majority opinion, but not all of it. Justice Sotomayor wrote a dissent that was joined Justices Kagan and Jackson, and Justice Jackson dissented separately as well. That’s a lot to keep track of. The opinion is also difficult because it’s not written for public consumption. In a case like this, it would be great if the Justices tried to make it more readily comprehensible, even with a few summary paragraphs, but they did not.

We’ll work our way through the majority opinion tonight. I apologize for how long this is—I tried to be descriptive of the reasoning in the opinion without injecting too much of my own commentary, but that proved difficult and in places, impossible. Still, I hope you’ll be able to work your way through the full opinion, even if you have to do it in different readings. And please leave me comments in the forum if anything is hard to follow. I’ll do my best to continue writing about this so we understand as much as possible by the time we’re done with it.

If the Chief Justice hoped, which he should have as a self-described institutionalist, to write a credible opinion that brought clarity to the law, he failed. He didn’t come close to having a unanimous decision; he only has a partisan majority on board with him. And the opinion itself is hard reading, even for appellate lawyers or those used to contemplating constitutional issues. It’s not law written for the public, and that’s an abdication of the Court’s responsibilities in this case. Speaking of abdication of responsibility, both Justice Thomas and Justice Alito participated in the decision, an ongoing sign of the ethics dysfunction at the Court. This Court has frittered away public confidence in its integrity as a democratic institution just when it’s needed the most, as the 2024 election, which like the one in 2020 may well end up in the courts, draws near.

The Basics

The issue the Court agreed to decide when it took the case was whether, and if so to what extent, a former President enjoys presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office. They issued a fairly direct answer today, finding that there are three different categories of presidential conduct, and a different rule about immunity applies to each one:

A former President has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for actions within his “conclusive and preclusive” constitutional authority—his official authority stemming from the Constitution and our laws. This is for the exercise of his core constitutional powers.

He has presumptive immunity from prosecution for other official acts, unless the government establishes that permitting them to prosecute will not create a danger of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch. The Court calls this the “Twilight Zone” of official acts, which includes areas where a president has shared immunity with Congress.

There is no immunity for unofficial acts. Note that there may be an issue about how to decide whether conduct is official or unofficial, but if it’s the latter, no immunity.

If Nixon had known he had immunity like this, he wouldn’t have resigned.

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent, again, goes straight to the heart of the matter, noting that the Court gave Trump “all the immunity he asked for and more.”

Trump’s Response

Trump posted his reaction on Truth Social. It makes almost as much sense as the opinion itself.

The Majority’s Reasoning

This is where we’ll devote most of our time tonight, to the details of the majority opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts.

Any questions—drop them in the comments.

We now know from today’s opinion that whether a president receives immunity from prosecution for particular acts depends on whether they are deemed official or unofficial conduct. Core constitutional conduct gets absolute immunity. Other official conduct has “presumptive immunity,” which means that a president can’t be prosecuted for it unless the government can satisfy the court that prosecution won’t intrude on the authority and functions of the presidency. Unofficial conduct isn’t protected from prosecution, but it turns out the “unofficial” conduct may not have the common sense meaning we would naturally ascribe to it, something I’ve often phrased as the difference between conduct committed by President Trump and conduct committed by candidate Trump. Instead, it turns out it may be much narrower in scope.

Who decides what conduct is unofficial? It will ultimately be up to the same Court that reached this decision today.

Absolute immunity is for the president’s constitutional authority. These are the broad powers that belong exclusively to the president; they are “conclusive and preclusive” as the Court puts it. They note that “Congress cannot act on, and courts cannot examine, the President’s actions on subject within his ‘conclusive and preclusive’ constitutional authority.”

Presidents have additional official authority, which the Court refers to as “implied authority,” a “‘zone of twilight’” where a president may have concurrent authority with Congress. This is the area where the determination of whether a president gets immunity is the most difficult because the answer is, “it depends, but probably yes.” The Court says there is a presumption that immunity applies here, unless the government can show that a prosecution won’t impair the president’s performance of his official functions. That’s a highly subjective determination that the courts get to make.

This is one part of the opinion you might want to read for yourself. Starting at the bottom of page 12 at number 2, there is a section of the opinion that lays out the majority’s chilling vision. They care more about presidential power than about a president who tries to steal an election. They don’t want a president to have to worry about little details like breaking the law.

In this section, the majority addresses what it calls the “countervailing interests at stake”—using federal criminal law to address crimes. Despite those interests, they say presidents get “presumptive immunity”—that means it exists unless prosecutors establish that it doesn’t—and they say it’s not necessary for them to decide here whether Trump gets it or not at this stage. They do tell us, however, what test they will use when they get to the stage where that decision must be made:

“At a minimum, the President must therefore be immune from prosecution for an official act unless the Government can show that applying a criminal prohibition to that act would pose no ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.’”

It’s all about the power of the presidency.

The Court notes that “Distinguishing the President’s official actions from his unofficial ones can be difficult.” They write that its essential to understand the nature of a president’s authority to take a certain action before making a decision about whether he has immunity. But they set out some guidelines that make clear that immunity is broad, perhaps all encompassing in this case. Key points include:

Absolute immunity extends to the “outer perimeter” of a president’s official responsibilities, covering anything that isn’t “manifestly or palpably beyond” this authority.

To distinguish official from unofficial conduct, courts “may not inquire into the President’s motives.” In other words, the fact that Trump wanted to overturn the election can’t be considered for this purpose. That’s shocking, but consistent with the tone of the entire opinion. The Justices seem to exist in an ivory tower where they debate presidential power without seriously acknowledging that they’re talking about a former president who would have happily fomented insurrection to stay in office after he lost.

An action isn’t unofficial “merely because it allegedly violates a generally applicable law.” Presidents can break the law while acting in their official capacity, but this is something more than that. The Court prohibits the district court from looking at whether a president’s conduct violates the law to decide whether its official or unofficial. That means an arguably official act stretching up to the outer perimeter of official duties gets immunity even if it’s, say, killing someone. This is all of the nightmare hypotheticals about was a sociopathic president could do without consequence. Now, the Court has said they can.

The Supreme Court offers Judge Chutkan some highly specific guidance for doing her job, directing her to find that a president’s conversations with Justice Department officials fall within the president’s official duties and are hands-off. It doesn’t seem to matter to the Court that those communications were about pursuing investigations into voter fraud when DOJ had determined there wasn’t any, or to put it more baldly (the majority opinion doesn’t) convincing DOJ to use its gravitas to suggest Trump won an election he lost. Apparently, a president can ask for an investigation into anyone or anything that’s in their way and have immunity from criminal prosecution. Trump can’t be prosecuted for trying to enlist DOJ in his scheme to steal an election. This falls within the core functions of the presidency bucket of official action.

The Court treats the DOJ example as cut and dry for immunity. There’s a different result for Trump’s effort to enlist Vice President Mike Pence in the scheme to block certification of the election. The Court says that because a discussion of their duties between the president and vice president is “official conduct” Trump’s efforts to pressure Pence “involv[ed] official conduct,” so he is “at least presumptively immune from prosecution for such conduct.” This section of the opinion suggests that the “Twilight Zone” category of conduct qualifies for presumptive immunity so long as it “involves official conduct.” That’s really troubling because it has the potential to dramatically narrow the scope of unofficial conduct, the only area where the Special Counsel is able to prosecute Trump.

The Court sets out a process for making determinations in this area:

First, decide if the conduct merits presumptive immunity, i.e. if it “involves official conduct.” The majority chastises the lower courts for failing to address this issue, which they call the “critical threshold issue” in this case.

Second, if it does, “the question then becomes whether that presumption of immunity can be rebutted” by prosecutors. To do that, prosecutors have to show that the President has no direct constitutional or legal authority in this area and that even though it “involves official conduct” prosecuting him does not “pose ‘dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.’” The Court points out that “applying a criminal prohibition” to a president’s efforts to bully and badger his vice president to take unconstitutional steps to help steal an election might “hinder the president’s ability to perform his constitutional functions.” That’s the test, no matter how outrageous the conduct. If it “involves” official conduct, a president can’t be prosecuted for it unless the prosecution won’t hinder his ability to perform his constitutional duties.

Third, the government bears the burden of rebutting the presumption of immunity. The Court says they can’t decide whether they met that burden here, since the trial court didn’t do this. So, they send the case back to Judge Chutkan and direct her to obtain “appropriate input from the parties” to decide whether prosecuting Trump for trying to influence Pence would “pose any dangers of intrusion” on presidential authority and function. This is an awfully squishy test. You could answer that as yes for virtually any prosecution in this middle category, which would mean it’s barred by immunity, and this Court certainly intimates that it’s likely to.

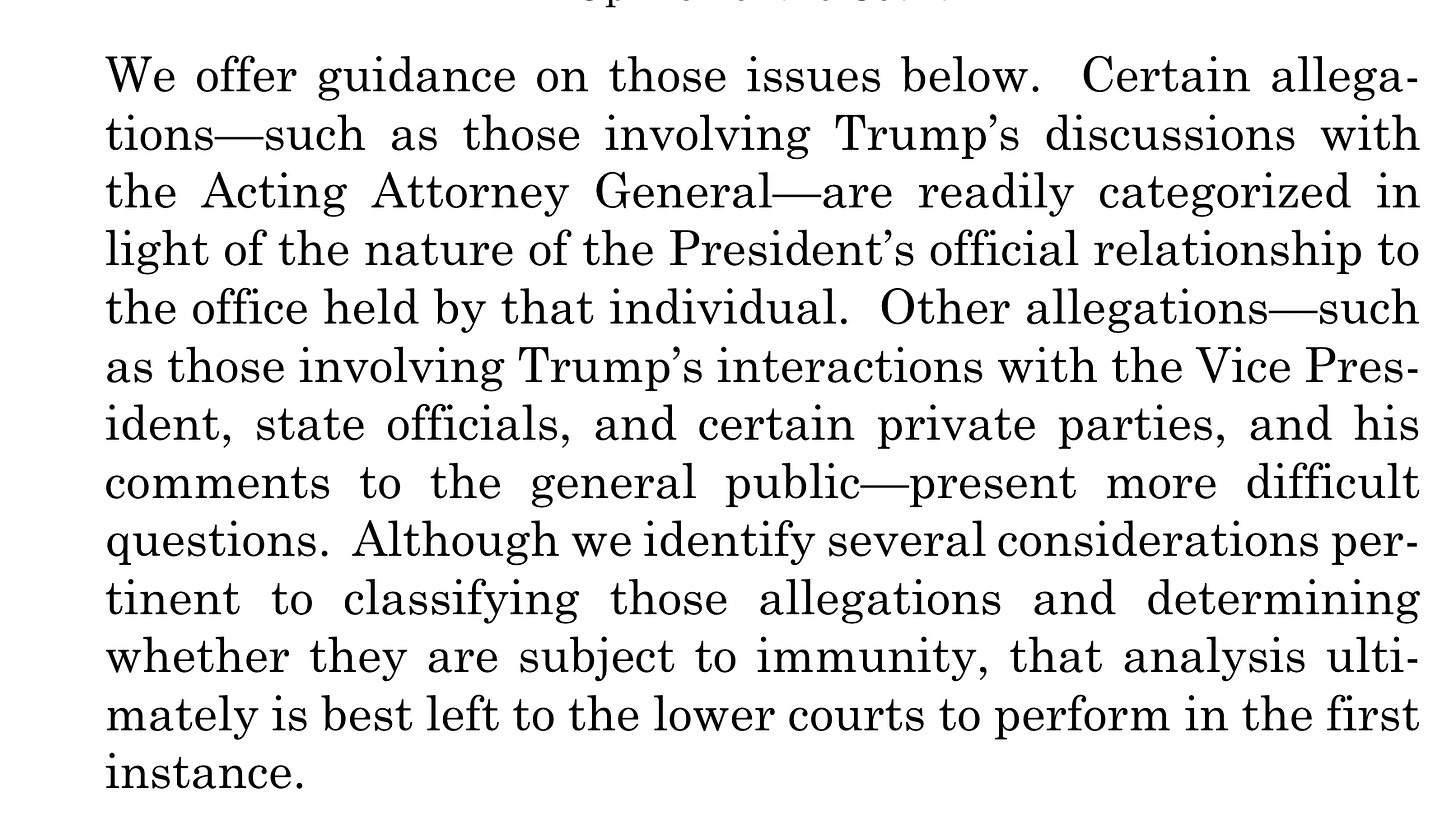

Beyond DOJ and Pence, there is other conduct charged in the Special Counsel’s indictment involving Trump’s interactions with people outside of the federal executive branch of government. This is what I would call conduct by “candidate Trump,” not President Trump. But the Court doesn’t seem to see it that way. Instead, they spend some time, despite Trump’s concession that this conduct was not about official acts, resurrecting the official status of what Trump did, pointing out that he had argued, for instance, that it was part of his duties to communicate with state officials about the integrity of federal elections and to take care that that laws are faithfully executed—apparently, they didn’t see the hypocrisy embedded in making that argument in regards to Donald Trump.

The Court also mentions Trump’s conduct in connection with January 6, including Tweets and efforts to steer the crowd on the Ellipse to the Capitol. The Court says it’s possible he could address the public in “an unofficial capacity” so there needs to be an “objective analysis” of the communications. But they caution there is “not always a clear line between [the President’s] personal and official affairs” so this analysis may be “challenging.” Presumably that’s a caution to the government.

The Court sends all of this back to the district court “to determine in the first instance—with the benefit of briefing we lack—whether Trump’s conduct in this area qualifies as official or unofficial.” They’ve designated the district court as their fact finder but made it clear that while Judge Chutkan gets to track a crack at the decision in the first instance, it’s up to them to make the final call. And it’s worth noting that while they have no trouble finding Trump gets immunity for the DOJ allegations and likely does for Pence, they don’t rule in anything as conduct that can be prosecuted—reading this opinion, there is no conduct the Court has said Trump can be prosecuted for. Justice Sotomayor makes this point in her dissent, but it’s something that is striking after reading the majority opinion. It’s like watching a baseball game where all the balls are called as strikes to benefit the home team.

That’s most of the meat in the opinion. There is still an interesting section of the opinion, IIIC, which Justice Barrett does not join. That means it’s a 5-4 majority for this important section of the decision, with Justice Thomas and Justice Alito both included as part of the five. This part of the opinion is about whether the government can use official conduct it’s barred from charging because of presidential immunity as evidence to prove the remaining charges. In its brief, the government argued that this was the case, but the Court said no, returning to its concerns about presidential power and functioning. “Use of evidence about such conduct, even when an indictment alleges only unofficial conduct, would thereby heighten the prospect that the President’s official decisionmaking will be distorted.”

In other words, it’s all about protecting that collection of presidential power. Judge Chutkan wrote in her immunity opinion that it wouldn’t be a bad thing for a president to consider whether he’d be committing a crime before he took action. The Supreme Court landed 180 degrees the other direction. According to them, immunity means a president can’t be indicted for conduct he’s entitled to immunity for, and no evidence of that conduct can be used against him. This is the type of evidence of uncharged conduct that could typically be used to establish motive or intent, but it’s off the table here. It’s a significant blow to the government in prosecuting its case.

Justice Barrett wrote, in a footnote to her concurring opinion, that "Sorting private from official conduct sometimes will be difficult—but not always. Take the President's alleged attempt to organize alternative slates of electors. In my view, that conduct is private and therefore not entitled to protection." In a footnote, she does what the rest of the majority fails to do, find a single instance of conduct for which they are willing to go on the record as saying Donald Trump can be prosecuted.

The Chief Justice’s Criticism of the Dissenting Justices

The majority opinion closes with a section where the Chief Justice, in a most decidedly uncollegial fashion, criticizes the Justices who dissent. He starts by calling out the dissents for striking “a tone of chilling doom that is wholly disproportionate to what the Court actually does today.” Sit down, little ladies, the Chief Justice might as well have said. Roberts tries to downplay what the Court is doing, but essentially, that comes down to saying that all that the Court is doing is saying Trump is entitled to immunity for his attempt to get DOJ to legitimize his efforts to steal the election.

Perhaps worst of all is an argument the majority offers as its own that is straight out of Trump’s playbook. And the dismissive language they use towards the dissents is really outrageous: “Unable to muster any meaningful textual or historical support, the principal dissent suggests that there is an ‘established understanding’ that ‘former Presidents are answerable to the criminal law for their official acts.’ Conspicuously absent is mention of the fact that since the founding, no President has ever faced criminal charges—let alone for his conduct in office. And accordingly no court has ever been faced with the question of a President’s immunity from prosecution. All that our Nation’s practice establishes on the subject is silence.”

We all know the answer to this one—no president has been prosecuted because no president has ever done what Trump did before. We all believe, or at least have until today, as did the Founding Fathers, that no man is above the law, not even the president. Everyone seems to understand that except for six conservative justices on the United States Supreme Court. “Our dissenting colleagues exude an impressive infallibility,” the Chief Justice writes. It’s a shame he cannot see himself in the mirror.

It’s only in the closing paragraphs of the majority opinion that Roberts addresses, without mentioning him by name, the would-be authoritarian on whose behalf he is willing to suspend the Constitution: “This case poses a question of lasting significance: When may a former President be prosecuted for official acts taken during his Presidency? Our Nation has never before needed an answer. But in addressing that question today, unlike the political branches and the public at large, we cannot afford to fixate exclusively, or even primarily, on present exigencies. In a case like this one, focusing on ‘transient results’ may have profound consequences for the separation of powers and for the future of our Republic.”

It’s remarkable that the Court is able to go on for 43 pages without acknowledging that Donald Trump tried to undo our democracy. Not in an attenuated theoretical sense, but in a very real one. George Washington, whose name Roberts invokes, would have had no difficulty calling Trump out for the scoundrel he is, for the threat he poses to democracy. The conduct that the majority protects—it’s all part of his efforts to steal an election he lost. And the future that they are so concerned about protecting? What they’ve done is write a road map for future wrongdoers, including Trump if he’s reelected, to avoid accountability for acts committed while in office.

As Justice Jackson writes in her dissent, the majority is overly worried about the chilling effect the absence of immunity could have on the exercise of presidential authority by a powerful and bold president. The proper concern is the opposite of that, the abuse of power by a too-powerful, possibly corrupt president. That’s what the Framers sought to avoid.

The dissenters are correct. I, too, fear for democracy.

Delay, Delay, Delay

The bottom line here is that there will be no trial before the election. There may be further proceedings in the trial court, but a jury of Donald Trump’s peers will not determine whether he tried to interfere with the 2020 election before voters return to the polls in 2024. That shouldn’t have happened; the Court had plenty of opportunities to do this in a timely fashion. Now, the Court is on the ballot, along with Donald Trump.

Fifty-four percent of registered voters say Donald Trump should not be running for president, according to a new CBS-YouGov poll. The New York Times has called for Biden to resign because of his age and debate performance, but not Trump. It took the Supreme Court almost ten weeks to issue its decision in this case following oral argument. That delay was of immeasurable benefit to Donald Trump.

Final Thoughts

We each have the opportunity to join Justice Sotomayor in dissenting when we vote in November. The Court’s decision means that the only force that can hold Trump accountable for trying to interfere in the last election is the voters in the coming one. It’s up to us, because the Supreme Court has said the rule of law no longer applies to the President. We held Trump accountable at the polls in 2020 and must do it again in 2024, because the Supreme Court won't. So, I will dissent too.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

.

Joyce, we just have to get Biden elected. We all know we deal with an administration, not just a President and Joe has a strong one. Frankly, I feel so anxious I had to take the evening off of work. I have seen Pres. Biden in person recently and he's been fine. He was fine before and after the debate. I'm really confused and concerned for our future.

With this Court, one can possibly argue - despite Gorsuch's "one for the ages" claim - that this decision, and Roberts' own opinion for the majority, was aimed at and tailored for tRump in particular, and that a *Republican* AG could indict a former Dem president for "criminal actions" that upon appeal to this Court, would fail the *official acts* criteria and be dumped into the prosecutable "unofficial acts" bucket. I mean, tRump and cohorts have for months talked about prosecuting Joe Biden for his "corrupt and criminal behavior", and who among us would gainsay SCOTUS greenlighting these prospective actions by the same tortuous logic?

A roadmap for authoritarian, anti-constitutional rule, folks, it's there in black and white.