It’s turning out to be one of those weeks! Normally I’d be writing about DOJ’s declination on the Matt Gaetz prosecution. But tonight it only gets a couple of lines. Although it’s not the answer many people hoped for, I think the assessment of Dave Aronberg, the state attorney in Palm Beach, Florida, is correct. He tweeted that DOJ was probably concerned about basing a case against Gaetz on the testimony of Joel Greenberg, who, Aronberg pointed out, had been convicted of lying and “who had also previously tried to frame someone else for child sex trafficking.” A decision not to prosecute—what prosecutors call a declination—doesn’t always give someone under investigation a clean bill of health. Sometimes it means the government doesn’t think its evidence is strong enough to convince every member of a jury that the defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

An interesting takeaway is that while prosecutors rarely make public a decision not to indict, we learn about them in high-profile cases because defendants like Gaetz want to make a declination known as soon as they’re advised of it, to try to clear their name. One way or the other, we’ll learn about the special counsel’s conclusions with regard to Trump at the end of his investigation, hopefully without the Bill Barr-style gaslighting of the public that followed the conclusion of the Mueller investigation. But if DOJ had already made decisions not to prosecute defendants who are lower down the food chain than Trump, we’d likely know about it, just as we’ve learned about the Gaetz case today.

Tonight, CNN is reporting that Special Counsel Jack Smith subpoenaed Mark Meadows to testify in front of his grand jury. That doesn’t seem surprising in any way. You’ll recall that Meadows cooperated with the January 6 committee, until suddenly he didn’t anymore. Then Congress referred him to DOJ for prosecution for contempt. DOJ declined to prosecute. Now DOJ has issued their own subpoena for him. Let the games begin again.

Sending a subpoena suggests Meadows is not cooperating with Smith. Meadows, who seems to the naked eye to have a great deal of exposure to criminal charges of his own, would be wise to try to cut a deal with prosecutors in exchange for his testimony. Perhaps cooperation was under consideration but didn’t work out, and the subpoena was filed after it became clear Meadows had decided against cooperating or wasn’t cooperating truthfully and completely. We don’t know precisely what the situation is, but it’s unlikely the subpoena is a disguise to make it look like Meadows isn’t cooperating when he really is, as some have suggested. There’s little reason to do that here. Meadows is a known quantity, and his text messages are already out there for the whole world to see. And prosecutors would probably want Trump to know if Meadows was cooperating. It ups the ante.

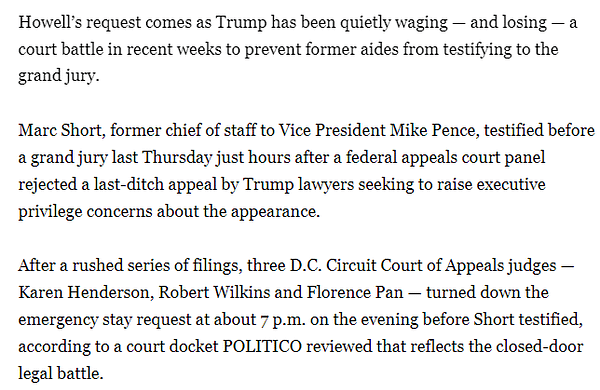

First up for Meadows will probably be an effort to use executive privilege to block the subpoena. But as we discussed earlier, that argument seems to have played out against similar efforts to duck an appearance before the grand jury. It’s unlikely there’s anything unique in Meadows’s situation that would excuse his appearance pursuant to a federal grand jury subpoena. NYU Law Professor Ryan Goodman has an excellent thread laying out all the ways the executive privilege argument has been a loser for members of the Trump administration and the former president’s inner circle.

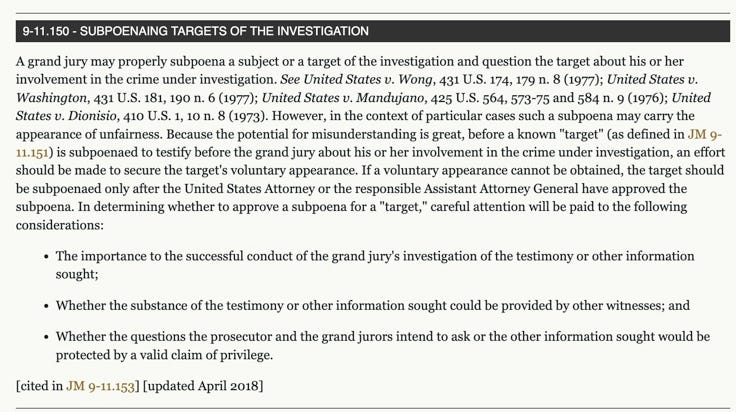

Meadows was heavily involved in Trump’s pursuit of the Big Lie, which raises another question: whether he’s a target of the investigation. The Justice Manual, the federal prosecutor’s bible, defines a target as “a person as to whom the prosecutor or the grand jury has substantial evidence linking him or her to the commission of a crime and who, in the judgment of the prosecutor, is a putative defendant.” That’s DOJ-speak for someone who a prosecutor is fixing to indict.

Targets aren’t typically subpoenaed to testify, but DOJ policy does permit it, in carefully defined circumstances. Smith has the same authority as a U.S. Attorney here, so he could approve the subpoena on his own if Meadows were a target, so long as there’s been an effort to have him testify voluntarily first. Targets are most likely to testify when they have essential information other witnesses can’t provide, and particularly if that information involves different crimes than the ones the target is under investigation for. Here’s the provision in the Justice Manual that governs subpoenaing targets.

Meadows, if he is a target, would be able to use the Fifth Amendment to avoid testifying. Declining to testify because a truthful answer would tend to incriminate you sends prosecutors an awfully strong signal.

The real question at that point would be, how much does Jack Smith want Meadows’s testimony? He already has the text messages he provided to the January 6 committee. If he needs more and Meadows takes the Fifth, Smith can give him immunity from prosecution, which would force Meadows to testify, because once he can no longer be indicted, nothing he could say would be incriminating. That, of course, would also implicate Fani Willis’s investigation in Fulton County, Georgia, where Meadows could be a target as well.

There are a lot of known unknowns to consider here.

But Donald Trump probably feels even worse than Meadows tonight. Because Meadows knows a lot. We saw that in the text messages he provided to the January 6 committee—they provided a lot of the information the committee used to assemble its timeline of what happened and flesh it out.

Beyond Meadows, there’s more bad news for Trump this week. Jack Smith is apparently unsatisfied with the answers he received from Trump attorney Evan Corcoran before the grand jury in connection with the classified documents investigation. Corcoran would have invoked attorney-client privilege to avoid answering questions about his conversations with his client, the former president.

I’ve discussed this before in the newsletter, when John Eastman, a lawyer connected to the Big Lie, refused to give the January 6 committee his emails, claiming they were protected by attorney-client privilege. Here’s the substance of what I wrote back then:

The attorney-client privilege protects confidential communications between attorneys and clients, so long as they are made for the purpose of facilitating the provision of professional legal advice. To be confidential, communications must be limited to attorney and client, or in some cases their representatives. They must be for the purpose of seeking legal advice. If communications are used to commit or are in furtherance of crimes, they lose the protection the privilege normally provides.

There’s a two-part legal test used to decide when the crime-fraud exception applies. The client must have consulted an attorney “for advice that will serve [them] in the commission of a fraud or crime,” and the communications must be both “sufficiently related to” and made “in furtherance of” the crime. It doesn’t matter whether the defendant successfully pulled off the crime or not; it’s the abuse of the confidential relationship between lawyer and client that shuts off the protection these communications would normally receive.

DOJ will ask Chief Judge Beryl Howell to “pierce the veil” of the attorney-client privilege and order Corcoran to testify about conversations with his client. DOJ will bear the burden of showing that, more likely than not, the communications Corcoran declined to testify about were related to and in furtherance of crimes, most likely obstruction of justice in addition to the underlying mishandling of classified materials.

The facts here have an interesting similarity to the earlier case where a judge set aside the attorney-client privilege and forced Eastman to turn over some of his emails. Although that was a civil case and here DOJ seeks the testimony in connection with a criminal matter, essentially the same standard for piercing the attorney-client privilege applies. In the current case, DOJ is interested in how an affidavit that falsely attested that Trump turned over all of the classified material in his possession came to be submitted to DOJ. In the Eastman matter, Trump himself signed a verification for one of the federal lawsuits challenging the 2020 election, even though he knew the numbers in it were made up. Prosecutors will try to convince the judge that the conversations between Corcoran and Trump were for the purpose of obstructing the federal investigation into his ongoing possession of classified material at Mar-a-Lago. For those keeping score, that would be the second time a judge found that the former president abused the attorney-client relationship to help in the commission of a crime, another first for Trump.

Here’s my earlier piece on the Eastman case and attorney-client privilege.

Smith understands that when you come for the king, you’d best not miss. It sounds like he doesn’t intend to; he’s leaving no stone unturned as he issues subpoenas, which is what one might have expected DOJ to do as soon as Merrick Garland took the reins. Better late than never.

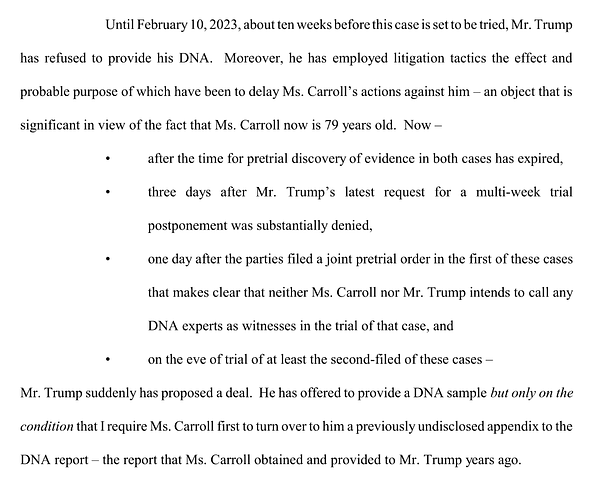

Also, a little news in the E. Jean Carroll defamation case against Trump, which is slated for trial next month. Trump tried an 11th-hour effort to delay the trial, again, by offering to provide a DNA sample. Carroll kept the dress she was wearing on the day she says Trump raped her. The time involved in obtaining and processing a sample could mean months of delay with little evidentiary value (old DNA on a dress that’s been hanging around for a couple of decades could be so intermingled with other DNA or degrading elements at this point that it wouldn’t be of help). Neither side is planning on calling expert witnesses on DNA. Fortunately, the judge saw the offer for what it was and declined to let Trump delay the trial.

My favorite news tonight is that our chicken coop is in progress, despite some heavy-duty weather going on here. Expect happy chicken pictures over the weekend!

That does it for me tonight. Happy partial release of the Fulton County grand jury investigation report eve to all who celebrate. Since the judge expressed great concern about protecting the due process rights of people under investigation, don’t expect to see a naming of the names. But it might still be interesting. We could get some sense of the grand jury’s working assumptions—did they, for instance, believe the evidence established that Joe Biden legitimately won Georgia and Trump was the one working to steal the election? We may also get an ultimate conclusion about whether they made some recommendations to prosecute. But don’t expect much specificity or you’re likely to be disappointed.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

I love the new chicken coop (in progress) and I love this: "Happy partial release of the Fulton County grand jury investigation report eve to all who celebrate." Most of all, I love being able to get your clear analysis after a day with no time or stomach for news. Many thanks.

How did this all happen? I can see one man thirst for power and money and commit a crime along the way. But to have so many other people involved along with him committing so many illegal acts to help him reach his goal is just so hard to believe or understand. It’s in times like this I always like to say “this gives me a brain cramp.”