Sometimes, it gets personal.

My daughter is finishing up a master’s degree. Her work is completely over my head, but it involves the intersection of nutrition, agriculture, and climate change.

She explained it to me like this: “This kind of research, which integrates climate science with human health, is essential for understanding how we adapt to the consequences of climate change. When you’re looking at crop growth in a certain climate, that mostly involves an understanding of soil science, pest management, water and fertilizer, and of course meteorology. But when you start to talk about the relationships between these things and livelihood and resilience, human health is a crucial element. For researchers who study these topics with complex lab equipment, high-speed data processing, or human participants, adequate funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is crucial to maintain the integrity of their research and ensure their ability to contribute to groundbreaking science.”

In other words, she’s doing important work, real work that could help make many lives better. She hopes to continue her work at the Ph.D. level, but it’s the kind of work the Trump administration’s new policy on NIH grants, which is now the subject of two lawsuits, would seriously hamper. All sorts of important research, and the training of Ph.D. candidates and others to do the work itself would suffer.

The new NIH policy slashes funding for what are called indirect costs, items like office space, utilities, and support staff. They fund research security, and biosafety. Now, NIH will limit indirect costs to 15%. Interviewed on NPR, Dr. Jo Handelsman of the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery said, “Cutting the rate to 15% will destroy science in the United States. This change will break our universities, our medical centers and the entire engine for scientific discovery.”

Megan Ranney, the Dean of the Yale School of Public Health, explained the impact to me like this:

“Our research is conducted on behalf of the federal government. Projects are selected by them and contracted with them.

And ‘indirects’ are reimbursements for costs incurred - lab safety, human subjects protection, IT, and more. They are negotiated every 3-5 years based on actual costs. They are literally part of the cost of doing research. So these cuts mean that the costs of research will not be covered, and many trials and as a result, some studies (whether with humans, animals, or data) simply will not be able to happen. This will have huge short- and long-term effects on human health.

Cutting indirects also has an immediate economic impact on all of the people who are employed in these research support roles. And it has a longer term economic impact: 14 new companies were launched in the last year based on federally funded research conducted at my university alone, and each of these supports its own health and economic ecosystem. This economic effect is present in every state and at every university across the country.

We've of course received stop orders on countless studies already - but worse yet are the studies that will never start, on everything from the environmental causes of Alzheimer's, to new tests for cancer, to novel treatments to improve adolescents' mental health.

These cuts will also have negative effects on the next generation of scientists, who apprentice with experienced researchers to learn the ropes. When studies stop, the next generation will not be able to train or learn. The effect of NIH cuts will be truly generational.”

Here in Birmingham, where the University of Alabama at Birmingham conducts groundbreaking research, officials made a statement about the cuts, which they noted would slow “Advancements in virtually all areas of research … including those addressing the leading causes of death in the United States, from cancer to Alzheimer’s, stroke, Parkinson’s, heart disease and diabetes, among other diseases and disorders that devastate lives and families.” They reported that it would also result in economic and job losses—NIH grants fund 4,769 jobs in Alabama, with an economic impact of $909 million. Now, imagine that multiplied out across the country.

But there is good reason to be more hopeful today than when the cuts were announced last Friday. In just those few days, the lawyers have been at work. In addition to the lawsuit brought by state attorneys general that we discussed last night, there is a new lawsuit, also in federal court in Massachusetts, brought by universities whose work will be damaged by these measures.

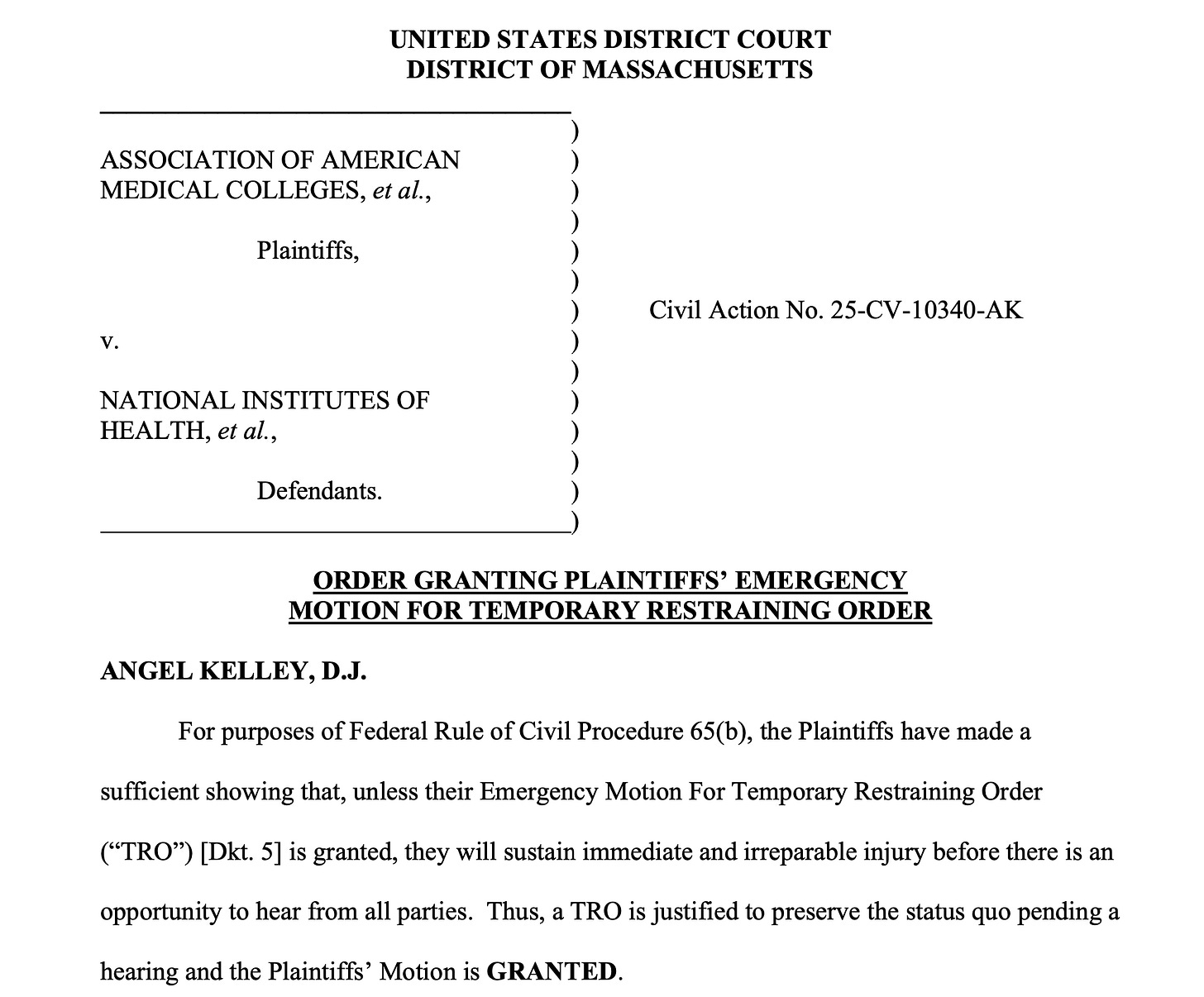

Judge Angel Kelley in Massachusetts entered a TRO in that case too, preserving the status quo and keeping payments in effect nationwide for now. She has scheduled a hearing for February 21 in both cases to decide whether to enter a preliminary injunction that would effectively keep the pause on Trump’s plan to cut the NIH funding in effect while the litigation proceeds.

Writing this piece tonight has been a gift. It’s given me the excuse to get my daughter to explain her work to me in more detail. I think she’s slightly amused that the specifics of the science elude me. But what I get loud and clear is this: underfunding NIH grants isn’t the kind of savings that benefits the American people. It does exactly the opposite.

She put it very eloquently: “My work is in understanding climate adaptation and resilience in agriculture and food systems through methods like systems modeling and collaborative research. It is important work. My kind of work can ensure that our food system is prepared for the emerging challenges related to climate change. Because this kind of research incorporates human health into a larger ecological framework, human-oriented funding is essential. I'm not just looking at crop growth, I'm trying to understand the climate protective elements of introducing a new crop into a community's diet. This is why NIH funding is important!”

Somehow, Bob and I managed to raise a kid who wants to make sure people have enough to eat. I am incredibly proud.

Doing less research won’t make the country better off. Research isn’t waste or fraud. We all benefit from it.

Minnesota Governor and former Democratic Vice Presidential nominee Tim Waltz made that point, referencing the Mayo Clinic in his home state. The research they conduct includes work on cancer, Alzheimer’s, and infectious diseases

As for waste, Donald Trump’s weekend trip to the Super Bowl reportedly could have cost as much as tens of millions of dollars between the flight and the security. During his first term in office, Trump family members’ travel, much of it business related, cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. As the Washington Post put it following his first month in office, “Barely a month into the Trump presidency, the unusually elaborate lifestyle of America’s new first family is straining the Secret Service and security officials, stirring financial and logistical concerns in several local communities, and costing far beyond what has been typical for past presidents — a price tag that, based on past assessments of presidential travel and security costs, could balloon into the hundreds of millions of dollars over the course of a four-year term.” If DOGE wants to cut costs, maybe instead of gutting cancer research, they should start there?

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Part of the NIH granting was for St Jude’s Children’s Hospital. What is wrong with these Administration idiots. The outrage for this should not know any political lines. News organizations gotta keep the pressure up.

This is what you get when deeply ignorant people (Trump, Musk, Trump’s nominee for HHS head) are given decision authority far beyond their capability.