What We Learned from Arraignment

Not a lot.

Arraignment is usually perfunctory, and Trump’s was no exception. The defendant pleaded not guilty. He was released on his own recognizance—that means he didn’t have to post a bond. It seems like a pretty safe bet that someone who has the Secret Service guarding them 24/7 isn’t going to slip quietly out of the country.

No sense yet of what sort of schedule Judge Aileen Cannon intends to adhere to and how quickly she will get proceedings underway. But we will get some sense of how she intends to run the case based on whether she begins to set deadlines for what she wants from the lawyers.

Alaska Senator Ted Stevens was indicted on corruption and fraud charges in late July 2008 by the Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section (PIN). The indictment came just ahead of the election that year. Stevens demanded a prompt trial. Appearing before a judge in the District of Columbia two days after the indictment, Stevens’ lawyer asked for a prompt trial. He said that Stevens wanted to “clear his name before the general election.”

Stevens got his speedy trial but was found guilty in October and lost the election in November. Nonetheless, his response was the response of a man who did not believe he was guilty—he wanted the chance to quickly clear his name. At least so far, that has not been the former president’s response to being indicted.

The Stevens case ended on a different note, with the conviction reversed on appeal. Prosecutors had failed to disclose exculpatory evidence to the senator in advance of trial. That’s a serious violation of discovery rules, the sort of misbehavior that, if intentional, violates prosecutors’ ethical obligations. Here, the judge found that it significantly impacted the ability to put on a successful defense. There were allegations that prosecutors knowingly permitted a witness to commit perjury about critical matters. The conviction was reversed, and an investigation ordered by the trial judge concluded DOJ had engaged in “significant, widespread and, at times, intentional misconduct.”

An interesting connection: In the wake of the Stevens debacle, a new prosecutor took over PIN. It was Jack Smith, the special counsel who indicted Trump last week on federal charges. When Smith took over, PIN was still reeling from the fallout of the Stevens case. Smith proceeded to clean house, closing other cases and restoring morale in the unit. Part of that housecleaning involved a decision to close investigations into other members of Congress without charging them. In the face of criticisms that the reputedly hard-nosed federal prosecutor from Brooklyn had lost his nerve, Smith told the New York Times, “If I were the sort of person who could be cowed, I would find another line of work.”

Like any prosecutor who tries the hard cases, Smith has had successes and failures. But it may ultimately be the recovery work he did after a case he played no role in prosecuting that has most informed who he is as a prosecutor. Prosecutors learn a lot from watching skilled colleagues prosecute their cases, but there are few lessons as valuable as the ones gleaned from having to pick up the pieces from a case gone badly wrong. It reinforces the value of candor, of getting cases done right and in the right way. The Stevens team was a blot on the Department’s image. But Smith’s opportunity to learn from those mistakes may serve him well in the Trump prosecution.

Can the Government Prove Its Case?

Much has been made of the fact that some of the juiciest details in the indictment appear to come from Trump attorney Evan Corcoran. But Corcoran is, apparently, not cooperating with federal prosecutors, who gained access to his extensive notes only after then–chief judge for the District of Columbia Beryl Howell ordered it. Corcoran is still on Trump’s payroll, although he is not longer working on the Mar-a-Lago case.

Judge Howell’s order is still sealed, but we know how she ruled. She found that the government was entitled to Corcoran’s notes because the attorney–client privilege that would normally protect the notes had to be set aside under the crime-fraud exception to the privilege.

So, where does that leave the government if some of its best evidence comes from a witness who doesn’t want to testify? Could Judge Aileen Cannon reverse Judge Howell’s ruling?

Second question first. A legal rule called the law-of-the-case doctrine means that an issue decided at one stage of a case is binding at later stages of the same case. Parties can’t endlessly relitigate the same issue over and over.

But Trump’s lawyers nonetheless will want to try and find an avenue to challenge Howell’s decision and prevent the government from using the evidence at trial. It’s too damaging to let it go without a fight, especially on the obstruction of justice charges.

Judge Howell is a serious jurist who wrote a lengthy opinion when she ruled. Because it’s sealed, we don’t know what positions she takes, but if it’s true to her reputation, it will be airtight. Trump’s lawyers may look for an exception to the law of the case—for instance, newly discovered evidence Judge Howell didn’t consider—and argue that Judge Cannon should prevent prosecutors from using the evidence at trial. But the indictment alleges Trump tried to prevent his lawyers from engaging in a thorough search and insinuated they’d be better off if nothing were found. If that holds up—and presumably it will or the government would not have included it in the indictment—Trump’s lawyers will have an uphill battle on their hands.

If Judge Cannon rules against the government, they will almost certainly try to appeal. While that’s less than ideal from a delay point of view, there is every reason to believe the 11th Circuit is primed to move quickly on these matters as they did with Trump’s civil lawsuit challenging the Mar-a-Lago search. Unless something unexpected emerges, it seems unlikely the 11th Circuit would alter the law of the case. The Supreme Court would probably treat it as they did the 11th Circuit’s Mar-a-Lago ruling, declining to hear it and speeding the case along on its way. Of course, “speeding” is always a relative term when it comes to the legal system and nothing here is certain, but if Judge Cannon adheres to the law, it’s likely the government comes out on top here.

With the clock ticking on the election season, every week will count. But if prosecutors are forced to appeal an outrageous decision by Judge Cannon in this respect, they could, at the same time, ask the appellate court that the case be reassigned to a different judge on remand. The law in the 11th Circuit speaks of recusal as the appropriate remedy for a judge who may have trouble putting aside their previous views and factual findings. One marker for that is repeated, outrageously wrong decisions. If Judge Cannon gets herself into this position by excluding the evidence Judge Howell permitted the prosecution to use, she might well find herself in recusal territory.

Assuming the government prevails and can use the lawyer-notes evidence at trial, there is still the first question to address: How does the government get the evidence in at trial if Corcoran isn’t cooperating? If Corcoran isn’t cooperative on the witness stand, the government can ask for permission to treat him as what’s called a hostile witness, and under the rules of evidence, that entitles them to take his testimony using leading questions. Normally, when it’s presenting its case, the government isn’t permitted to lead a witness. It must ask open-ended questions starting with words like “where,” “when,” “who,” and “how.” But leading questions are permissible when eliciting testimony from a hostile witness. Leading questions let the questioner preview the expected testimony and solicit the witness’s agreement: Isn’t it true that Trump didn’t tell you to search his office when you explained you needed to look every place where classified information might be located at Mar-a-Lago?

If the witness is combative or makes statements contrary to his notes, the government is entitled to read from it and confront the witness with his past statements. Ultimately, the government gets its desired testimony. It’s possible Corcoran’s posture vis-à-vis cooperation with the government could evolve in the months ahead of trial. Even if it doesn’t, the government will be able to get the substance of the information in the indictment into evidence in a manner that is always compelling in front of a jury.

Will We Get to Watch the Trial?

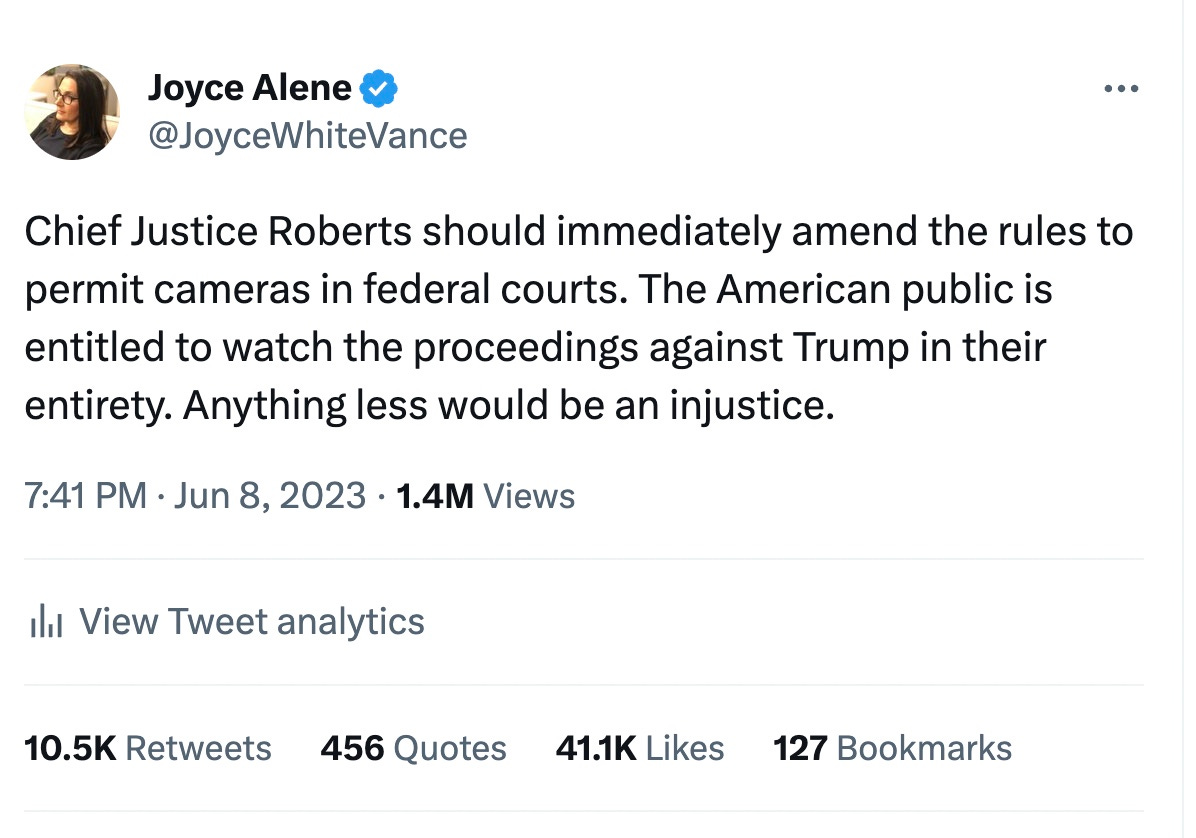

It seems senseless that the most important criminal case in our history will be conducted out of public view. But that’s how our federal courts work. There are no cameras in the courtroom. This case must be conducted in a manner that supports the public confidence that the proceedings are fair, and nothing does that like a little sunlight. It was one of my first thoughts when we learned Trump had been indicted.

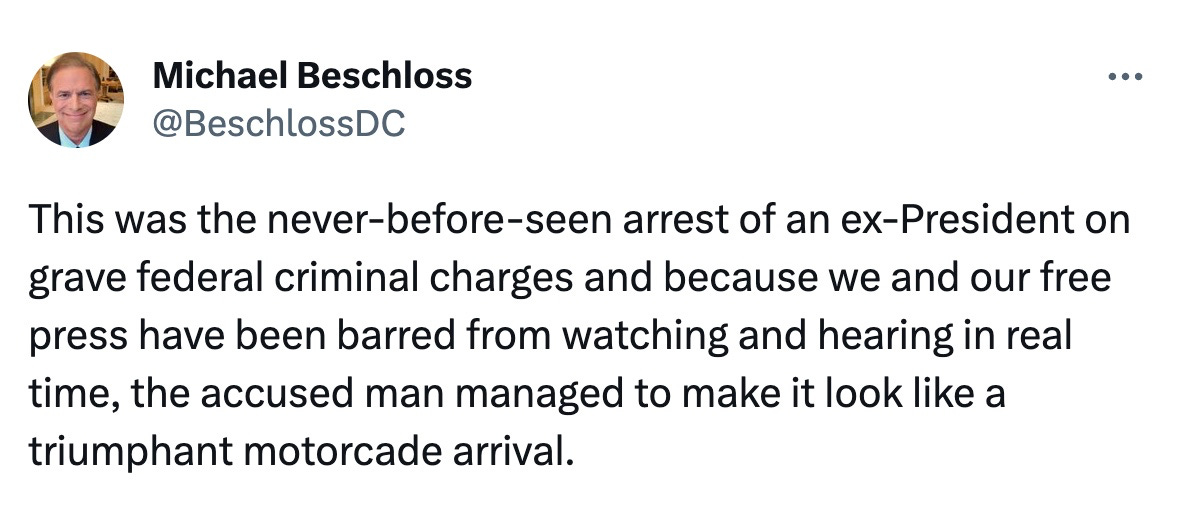

Although members of the press banded together to ask the magistrate judge who conducted arraignments Tuesday to permit cameras, he declined, indicating that because he would have no additional role in the case following indictment, it would be inappropriate for him to enter an order that would impact the rest of the case. Arguably, only the Chief Justice could alter the rules and permit cameras in the court. It’s essential that he do that here. Presidential historian Michael Beschloss explained why:

Like the Supreme Court did during Covid, the 11th Circuit livestreams its oral arguments. At a bare minimum the district court should adopt this practice for every proceeding in U.S. v. Trump. But if what we really want is for Americans to engage with the evidence and the arguments and appreciate the true facts in this case, there’s no way to convey the nuance like letting people watch the trial. Most courtroom proceedings are open to the public. Americans shouldn’t be excluded from the most important national courtroom because they can’t be physically present in Florida during the trial.

What Happens Next?

Lots of issues are going to fly off this indictment, and we’ll do our best to keep up. Trump’s former defense lawyer, Tim Parlatore, floated lots of possible defense motions he expected Trump’s team to raise—everything from prosecutorial abuses to motions to suppress. There will be legal arguments like the one Trump floated in his Bedminster speech Tuesday night about Bill Clinton’s sock drawer. Seriously. It’s too much to take on all at once, but we’ll keep plugging away to make sure we understand it all.

Expect issues and arguments to evolve along the way. Prosecutions don’t usually proceed along straight lines, and as we learn more about the facts, our legal analysis may change. But it’s an important process. And understanding these issues means you can help others understand them, too. All of this is worth our time and effort.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Going to school with you at the podium is always a good thing, Joyce, and fun to boot.

While concentrating on the text, it would have been criminal to ignore Joyce's title, 'Chickens Come Home to Roost' and Mike Luckovich's cartoon of the birds roosting in Trump's hair.

'The chickens come home to roost'

What does it mean?

'Bad deeds or words return to discomfort their perpetrator.'

'What's the origin of the phrase 'The chickens come home to roost'?'

'The notion of bad deeds, specifically curses, coming back to haunt their originator is long established in the English language and was expressed in print as early as 1390, when Geoffrey Chaucer used it in The Parson's Tale:'

'And ofte tyme swich cursynge wrongfully retorneth agayn to hym that curseth, as a bryd that retorneth agayn to his owene nest.'

'The allusion that was usually made was to a bird returning to its nest at nightfall, which would have been a familiar one to a medieval audience. Other allusions to unwelcome returns were also made, as in the Elizabethan play The lamentable and true tragedie of Arden of Feversham, 1592:'

'For curses are like arrowes shot upright, Which falling down light on the suters [shooter's] head.'

'Chickens didn't enter the scene until the 19th century when a fuller version of the phrase was used as a motto on the title page of Robert Southey's poem The Curse of Kehama, 1810:

"Curses are like young chicken: they always come home to roost."

This extended version is still in use, notably in the USA. (phrases.org.) See link below.

Joyce Vance solved the DOJ 's criminal case against Trump with chickens.

Now we know the true nature of Joyce's relationship with her chickens.

https://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/chickens-come-home-to-roost.html