Carroll, Continued

I expected to write about the Proud Boys trial this evening. The jury is now deliberating after almost four months in trial. The issues are serious—the allegation is that the Proud Boys, including leader Enrique Tarrio, formed a private army and agreed to use force to interfere with the certification of the 2020 election results. The five defendants now face judgment from a jury of their peers.

But before we do that, I want to turn to the E. Jean Carroll trial, where there was a lot going on today. Carroll took the stand, testifying at length before finally growing emotional near the end when she told jurors the support around the country "bouyed me up," but that the ugliness on the other end "swamped" those feelings. It was only at the end of her testimony that she finally gave in and cried, "I've regretted this 100 times, but in the end being able to get my day in court finally is everything to me. So I'm happy!" What a remarkable woman.

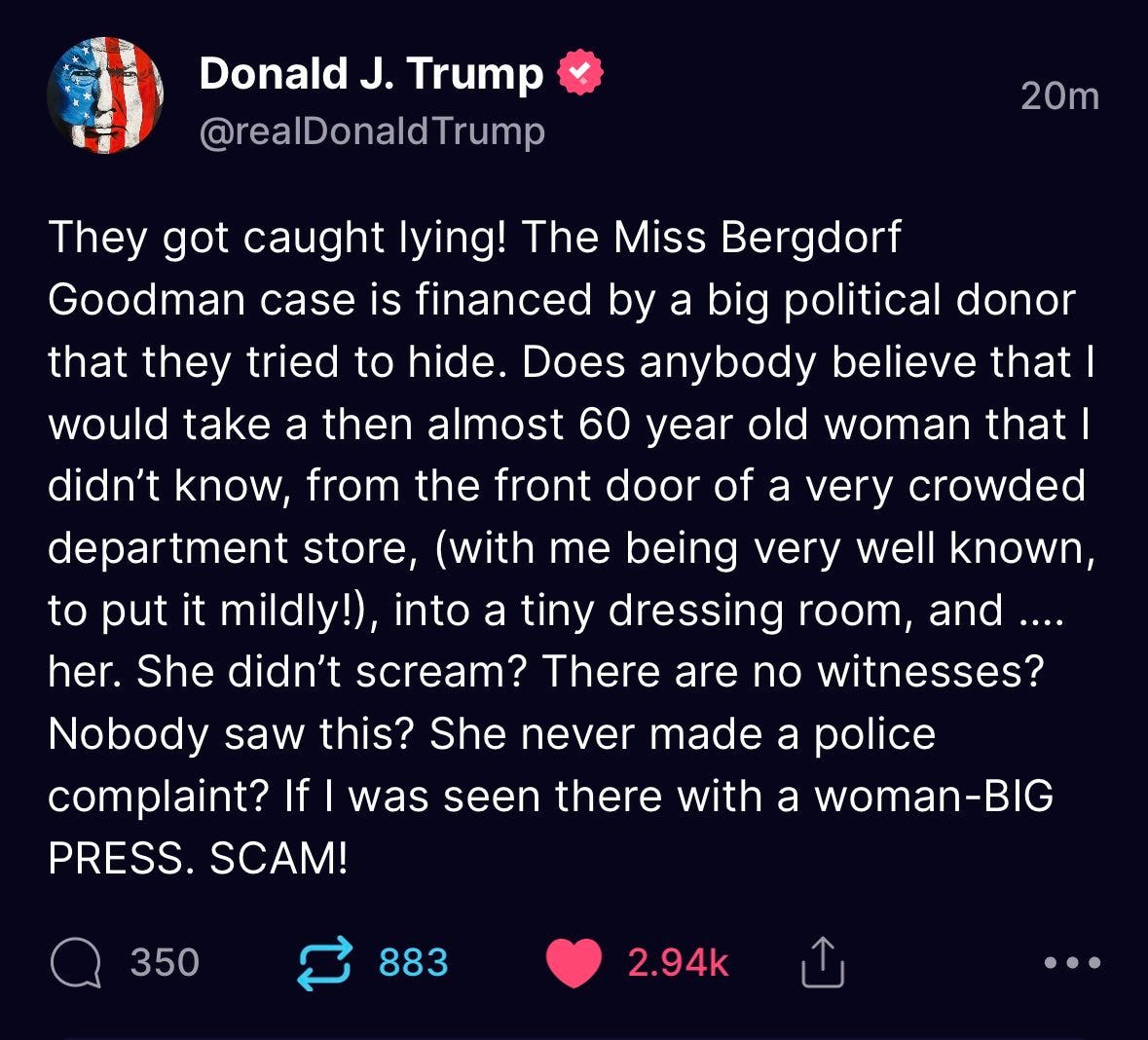

Before the testimony started this morning, Carroll’s lawyer advised the judge that defendant Trump, who has not been in and is not expected to show up in the courtroom, took to social media to tell his story in a venue that did not require him to testify under oath. He resorted to predictable name calling and seemed unable to do the math on Carroll’s age at the time he allegedly raped her.

The judge took Trump's derogatory social media postings seriously, telling his lawyer Joe Tacopina, "If I were in your shoes, I’d be having a conversation with your client." Later on he added, "there are some relevant United States statutes here and somebody on your side ought to be thinking about them,” in a not particularly subtle reference to the array of federal statutes that criminalize obstruction of justice, including the broad prohibition in 18 USC 1512 against even attempting to tamper with a witness, victim or informant, and other provisions that apply to jurors. While Trump’s conduct here probably doesn’t cross that line, the Judge is putting him on notice, early.

There was also some legal back-and-forth among the lawyers today about whether some of the evidence Trump’s lawyers wanted to introduce would be admissible. A little legal background will help us understand these arguments, which are likely to continue throughout the trial, over what evidence the jury can hear.

For instance, today, Trump’s lawyers wanted a ruling about whether they would be able to introduce evidence about Carroll’s past that painted her in a negative light, including evidence about her relationship with her second husband, John Johnson. Carroll testified about the relationship in her deposition, and there was some violence in the marriage. Trump’s lawyers wanted to introduce evidence that Johnson, who was Black, was provoked to violence when Carroll called him an ape. The judge, Lewis Kaplan, said that while they could get into the fighting, they could not get into the reason for it, because “it is a subject on which the unfair prejudicial effect outrageously outweighs any probative value, to a mixed-race jury in New York.”

This particular argument over the admissibility of evidence serves to illustrate the pertinent rules of evidence and will help us understand both this and other disputes about what evidence the jury can hear. Deposition testimony is wide-ranging and often goes beyond the bounds of what will be admissible at trial. The parties may acquire evidence in discovery that a judge ultimately rules isn’t admissible. The governing rules in federal court are federal rules of evidence 402 and 404(b).

Rule 402. General Admissibility of Relevant Evidence

Relevant evidence is admissible unless any of the following provides otherwise:

the United States Constitution;

a federal statute;

these rules; or

other rules prescribed by the Supreme Court.

Irrelevant evidence is not admissible.

But not all relevant evidence is admissible. The judge has the discretion to exclude relevant evidence if it’s cumulative—evidence of something that has already been overwhelmingly established. But the part of the rule, 403, which explains when relevant evidence can be excluded, that comes into play most often is a provision that permits a judge to exclude relevant evidence when it’s more likely to be unfairly prejudicial than probative.

Rule 403. Excluding Relevant Evidence for Prejudice, Confusion, Waste of Time, or Other Reasons

The court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.

The rule is more or less self-explanatory. The judge can keep evidence out of a trial if they believe it will distract the jury from getting to the heart of the matter.

Note the use of the word “unfair” in front of “prejudice.” All good evidence is prejudicial, in the sense that it helps to persuade a jury to rule in favor of one party at the expense of the other. Rule 403 only permits the exclusion of “unfairly” prejudicial evidence. The rule is meant to avoid injecting prejudice or bias, confusion or distraction, into a trial. These two rules, in combination, are the reason the judge excluded some of the testimony about Carroll’s marriage, based on his explanation that testimony could be unfairly prejudicial—in the language of the statute, its probative value is outweighed by the risk of prejudice.

The jury also won’t hear that George Conway, estranged husband of former Trump counselor Kellyanne Conway, was the one who connected Carroll with her lawyer Roberta (“Robbie”) Kaplan following a party at podcaster and writer Molly Jong Fast’s Upper East Side apartment. Nor will they hear that Kaplan’s firm received some funding that covered “certain costs and fees in connection with the firm’s work on Carroll’s behalf” from billionaire Democratic Party donor Reid Hoffman’s PAC. Kaplan advised the judge that Carroll didn’t personally communicate with the nonprofit organization or its financial supporters. In other words, none of this is relevant to the issues of whether Trump defamed or raped Carroll. The judge agreed to seal proceedings in that regard, with Carroll’s lawyer arguing it’s not relevant to any of the issues the jury has to resolve at trial. That’s the first principle: Evidence has to be relevant in order to be admissible. The factors set forth in rule 403 are used to limit the admissibility of relevant evidence. Like rule 402 says, “Irrelevant evidence is not admissible.”

So while we’re likely to hear talking points from Trump’s camp about how an unfair judge excluded important evidence, now you understand the rules and why Judge Kaplan ruled the way he did here.

One last point on Judge Kaplan’s rulings before we leave the topic. Trump’s lawyers are likely to appeal all of these rulings if the jury finds against him. He’ll try to get any verdict overturned, claiming the judge made reversible errors about the admissibility of evidence. There are standards of review on appeal that appellate courts use to assess the decisions made by trial judges. Decisions about the admissibility of evidence are within the discretion of a trial judge, and they will only be reversed on appeal if the judge abuses their discretion. Given the interplay of rules 402 and 403, Trump will face a high barrier if he tries to argue that any of these rulings unfairly tainted the trial.

We’ll continue to keep an eye on the Carroll case this week, but let’s close by returning to the Proud Boys. The verdict could come at any time now. The jury went home on Wednesday, their first day to deliberate, after several hours. Thursday will be their first full day of deliberations.

The five defendants are group president Enrique Tarrio, along with ranking members Ethan Nordean, Joseph Biggs, Zachary Rehl, and Dominic Pezzola. It was Tarrio who prosecutors allege ignited the conspiracy in late December 2020, after Trump tweeted at his supporters to descend on Washington, D.C., for a “wild” protest against the election results on January 6. Tarrio, concerned about a lack of discipline in the Proud Boys, formed a new chapter called the “ministry of self-defense” that included handpicked members he thought he could trust to follow orders. The ministry grew to several hundred members nationwide by the time the insurrection took place. Defense lawyers say the group was a glorified men’s club where the boys sat around and blustered, talking tough with little intent to do more than drink and spar. Prosecutors say this group formed the backbone of a “fighting force” that the Proud Boys sent into action on January 6.

The five are charged with crimes including seditious conspiracy, conspiracy to obstruct official proceedings, and conspiracy to prevent an officer from discharging official duties. Depending on whether and what charges each defendant is convicted of, they could be looking at statutory penalties of up to 20 years in custody, although the sentence called for under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines could be shorter in duration.

Jury verdicts are always hard to predict. This case is unusual in that much of the evidence is captured in the form of group messages or video from the 6th. Tarrio, who had been previously arrested in connection with other protests and barred from returning to the District, observed the day’s events from Baltimore. He communicated with them, sending messages like “Do what must be done,” “Don’t fucking leave,” “Proud of my boys and my country,” “1776,” and “Make no mistake we did this. Do it again,” as he watched them overrun the Capitol. Meanwhile, Nordean had assembled hundreds of Proud Boys at the Washington Monument on the morning of the 6th, and rather than attending Trump’s speech on the Ellipse, they marched to the Capitol, arriving while Trump was still speaking. Biggs spoke alone with a member of the crowd who, moments later, charged the police lines and started the stampede to breach the Capitol. Biggs and Nordean led the mob in taking apart a fence at the second police line, and in the chaos, Pezzola tore a riot shield away from a Capitol police officer that he subsequently used to shatter a window in the Senate wing of the building.

The defendants, of course, dispute the government’s view of the day’s events. Defendants Rehl and Pezzola took the stand in their defense. Rehl told the jury there was no plan to interfere with Congress or prevent law enforcement officers from doing their jobs, claiming that police let the protestors through the barricades. But Rehl’s testimony took a turn when prosecutors showed him freeze frames of video footage of a man who appeared to be Rehl and was wearing the clothing Rehl wore that day. Rehl got edgier and combative as he was shown a series of frames, finally depicting the man who looked to be him using pepper spray on a Capitol police officer. Asked if he had sprayed police officers, Rehl, who had exhibited a precise memory of the day’s events during his testimony, said, “Not that I recall.”

In closing, prosecutors acknowledge that the trial had been long and the evidence comes in “bits and pieces,” with “lots of interruptions.” This is often the case in long trials. Prosecutors take testimony from witnesses, and they don’t get to explain its significance or how it fits together to the jury until closing arguments. Here, the evidence gave prosecutors a lot to work with. In its closing argument, they referred to a message sent by Tarrio that said, “No Trump . . . No peace. No quarter.”

The jury will deliberate on each defendant separately and determine whether that individual defendant committed any or all of the crimes charged in the indictment. That suggests the jury will need at least a little time to review the evidence and reach decisions for each of the defendants. Trial lawyers roughly guesstimate a day of deliberations for each week of trial in a situation like this, but it’s just a rough guide. We’ll learn the jury has a verdict when there is a knock on the door from the inside of the room where they are deliberating.

What does any of this mean for Trump? There was no evidence of direct communication between Trump and the Proud Boys at trial, although their actions that day were animated by his public statements. He is not a co-defendant in their prosecution. But if the government succeeds with the charge of interfering with an official proceeding in this case, it will only add impetus to the special counsel’s investigation into Trump and those around him on a conspiracy charge of their own for doing the same thing in a different way—using fringe legal theories, slates of fake electors, efforts to take over the Justice Department, and, when all else failed, encouraging the mob to assemble and doing nothing to stop them when they overran the Capitol—in order to prevent Trump’s loss of the presidency from being formalized. So first we await the jury’s verdict in this case, and then we see where it leads.

For those of you looking for a quick refresher on conspiracy law while we wait, there is this post from last July, where my chickens were accommodating enough to demonstrate the basic principles involved.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

What a perfectly illuminating discussion of the legal issues involved in the Carroll and Proud Boys Trials. I especially appreciate your showing how all of the trails of evidence are being woven into alogical sequence leading to the prosecution of 45 on conspiracy charges. I take some hope from this, and of course, the chickens and watermellon are icing on the cake.

Wonderful article, Joyce. E. Jean Carroll is a brave woman. I try to imagine being in her shoes, and how scary it must be to give this testimony. First time in our history a former president is accused of rape and battery. Your detailed description of the legal process unfolding in this historic trial is also so helpful. It is riveting really. The Proud Boys information is also key to a deeper understanding of what happened on January 6. I await that trial’s outcome. Thank you, for your knowledge and humor. I love the photo of your conspiring chickens. They are beautiful....