Two cases, lots of motions to discuss.

We focus first on Trump’s motions to dismiss in the Mar-a-Lago classified documents case, which he filed late last week. These are only some of the motions pending before Judge Aileen Cannon, who also has discovery issues to handle and a scheduling conference later this week, on Friday. As with the election interference case in Washington, D.C., these are Trump’s dispositive motions, his shot at having some or all of the 31 charges against him in the Southern District of Florida dismissed.

In Manhattan on Monday, District Attorney Alvin Bragg filed three motions in advance of trial, scheduled to begin with jury selection on March 25. It’s clear from the motions that Bragg has gone to school on Trump’s behavior in other cases, both civil and criminal, and is trying to make sure he’s locked down as much as possible before this case goes to trial.

Mar-a-Lago

While these motions may not be entirely frivolous, there are some arguments that are perilously close to the line. In front of most judges, you’d expect to see them all rejected. We’ll see how that plays out here, and particularly whether Judge Cannon will wait for the Supreme Court’s assessment of the immunity issue or forge ahead on her own. The motions include the following:

Presidential immunity: The claim is that Trump designated all of the classified material recovered at Mar-a-Lago as personal records while he was president, and he cannot face prosecution for this official act.

The argument makes you wonder: under this rubric, would Trump also be free to do anything he wanted with his new “personal records”? Sell them to Russia? In other words, the argument, like the idea that Trump could order SEAL Team 6 to assassinate a political rival, should go too far for any judge to accept.

Presidential Records Act: This is the one Trump has been pushing on the campaign trail for months. The claim is that he designated all of this classified material as personal records while he was president, so he was entitled to keep it. Of course, there is no record that he ever declassified any of it. Trump argues that he has “virtually unreviewable Article II executive authority” but that doesn’t mean he can declassify the nation’s secrets in his own mind and walk away with them. The Presidential Records Act requires that the records remain in the National Archives’ control once a president leaves office, but Trump says the rules are too vague to enforce. Under Trump’s interpretation of the law, he could declassify the nuclear codes without telling anyone, claim they’re his records, and share them with hostile foreign powers, terrorists, or whomever the highest bidder happens to be. Legal rulings have consequences. Trump also argues that the only remedy for a violation of the Presidential Records Act is a civil one, designed to reclaim them, but that provision applies to actual presidential records, not the classified material Trump is trying to shield behind his pretzel logic about how these rules work. The only one who wins if Judge Cannon adopts Trump’s interpretation of these laws is Trump. America loses. Trump never confronts the highly sensitive nature of these materials.

The appointment of the special counsel isn’t lawful, so the case should be dismissed: Trump argues that appointing a special counsel violates provisions of the Constitution that would require Senate confirmation of this type of executive branch appointment. Tell that to Bill Barr, who as attorney general appointed John Durham and other special counsels. This would also be happy news for Hunter Biden, whose prosecution would be dismissed if Trump’s argument prevails. The argument flies in the face of the practice of using special counsels across multiple administrations, and at worst, if a court were to accept it, would warrant reassignment of the case to a DOJ prosecutor. In this unlikely scenario, some parts of a case might require a redo by the replacement prosecutor, but a defendant wouldn’t be able to avoid prosecution.

Trump rehashes the argument he made in the District of Columbia—and that Judge Tanya Chutkan rejected—that because he was not impeached and convicted by Congress for this conduct, he can’t be prosecuted now. The argument isn’t any better here than it was in D.C. In fact, it’s worse. For one thing, Congress wasn’t aware Trump held onto classified material while he was president; it didn’t come to light until he’d been out of the White House for almost a year. And much of the conduct, especially the obstruction of justice, occurred when Trump was no longer president, so even if his convoluted interpretation of the provision was accurate, there’s no reason that it would apply to this case.

Q Clearance: Trump has also argued he was entitled to keep the documents because he still possessed a clearance—an administratively granted “Q” clearance from the Department of Energy that wasn’t canceled immediately when he left the White House. We’ve discussed this argument previously. A key problem with it is that the clearance was only granted for use while Trump was in office, and merely having a clearance doesn’t permit storage of classified materials outside of special facilities.

Motions that are still under seal: Judge Cannon previously ordered that any motions that included information that either side believes is confidential should be filed under seal. Trump has suggested that his claims might include vindictive prosecution and a motion to quash the search warrant the FBI executed at Mar-a-Lago in August 2022, kicking the case into high gear.

There isn’t a clear winner among these motions, at least not once they are out of Judge Cannon’s hands, should she rule in Trump’s favor, and on appeal to the Eleventh Circuit. The real problem, as always, is the amount of delay involved in getting them properly decided.

Manhattan

The gag order and juror protection motions filed by District Attorney Alvin Bragg on Monday go hand in hand. Bragg is trying to protect his case from the sort of misbehavior Trump has demonstrated in other cases, ranging from outbursts in press conferences to attacks on witnesses, judges and court personnel, and prosecutors. The first two motions are an effort to head that off in this case.

Gag Order

The gag order the DA proposes is narrowly tailored to mirror the gag order the DC circuit recently upheld in the case before Judge Chutkan. This is important because judges have a comfort level when approving something that has previously withstood appellate review, particularly in a federal court of appeals. The DA offers exhaustive justification for preventing Trump from engaging in conduct that could prejudice the case while at the same time protecting his First Amendment right by permitting him to comment on the prosecution and proclaim his innocence.

Tucked into the hundreds of pages of exhibits that accompany the motion is a brief affidavit from the NYPD Sergeant who runs Bragg’s security detail. Exhibit 13 is an adjective-free recitation of the explosion in the number of threats against the DA, his family, and his staff after the Trump indictment. The numbers are stark, going from as little as one threat per year before the indictment to a: “peak, in March 2023, more than 600 emails and phone calls received by the DA’s office were forwarded for security review; this represents a small subset of the calls and emails received by the office relating to People v. Trump. Around this time, the emails, calls, and text messages received were directed not just to the DA or to the Office generally but also to senior members of the DA executive team and ADAs publicly associated with People v. Trump via both Office email or phone and personal email and phone. The messages received in March of 2023 were the first time I was aware of threatening messages relating to the work of the DA’s Office being directed at employees of the Office other than the DA.”

The threats made against Bragg personally were highly specific and graphic. They include threats to kill him, down to the type of weapon and scenario that would be used. Bragg nonetheless exempts himself from the order, and would permit Trump to continue to attack him, likely leading to more of this abuse and risk. That’s a feature that shows how reasonable Bragg’s approach is. Expect the Judge to adopt this with little, if any, modification.

Protective Order

Bragg asks the court to:

(1) prohibit disclosure of jurors’ addresses except to the lawyers in the case; and

(2) prohibit disclosure of jurors’ names except to the lawyers and to the defendant.

This would mean that the names of jurors couldn’t be disclosed to anyone who isn’t a lawyer in the case or a party in the case. If Trump were to share that information publicly or even selectively in private, he would be in contempt of the order and face serious consequences. And while his lawyers will see juror addresses, which may help them in their jury selection strategy, Trump can’t see them. This is reminiscent of an ask prosecutors might make in an organized crime case.

Motions in Limine

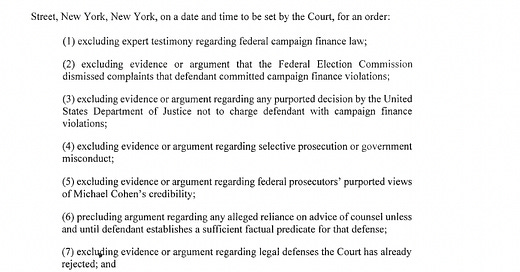

Motions in limine usually ask a judge to rule on the admissibility of evidence at trial. This motion is in this vein, but in an unusual way. In essence, it asks the Judge to rule that Trump can’t revisit legal arguments he makes and loses in front of the judge in front of the jury.

In a criminal jury trial, it’s up to the judge to decide issues of law. Issues of fact are left up to the jury. Once the judge makes a legal ruling against a defendant, he doesn’t get to make the argument to the jury in an effort to get a second bite at the apple. It’s over. A defendant doesn’t get to argue to a jury, for instance, that he’s entitled to presidential immunity after the judge rules against him—that’s not the jury’s decision to make.

This is assumed in the typical case, without need to make it the subject of a motion in limine. But this isn’t a normal case, and the DA has taken the extra step of asking the court to rule that the defense can’t introduce evidence on specific issues involving campaign finance law and other legal issues.

It’s encouraging to see this effort to head off the sort of tactics we’ve seen Trump egg on his lawyers to use in other cases. As the first Trump criminal case—a case with a jury in the box—it will be extremely important for both the Judge and the prosecution to be proactive in preventing a mistrial. Trump could provoke that with an outburst in court, or his lawyers could do it by introducing evidence that the jury shouldn’t hear. With mistrial comes delay. If they got into this situation, the prosecution would have to weigh whether it was more concerned about delaying the case or whether the jury’s decision might be fatally tainted by defense misconduct. Preventing that scenario will be one of the keys to this case and to the extent the court rules against Trump on legal issues, it’s appropriate to put his team on notice in advance that they can’t be raised at trial.

That’s a lot of legal ground to cover in one fell swoop, and it’s all high-level. We’ll be delving deeper into these motions as their turn in court comes, but for now, we have a baseline. Thanks for sticking with me through this and for being here at Civil Discourse. Your paid subscriptions permit me to devote more time and resources to this work, and I’m grateful that you’re here.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

“ That’s a lot of legal ground to cover in one fell swoop, and it’s all high-level.” By golly Joyce how do you keep it all straight?! Moreover, how do you keep from throwing things?😉. Trump is the most excruciatingly exasperating nauseating individual. His very presence steals oxygen from our world. But you dear Joyce help us along and I for one am ever so grateful!

How is it possible for one man to cause so much chaos? Trump has the Christian Right all caught up in politics (see David French). He has the courts in multiple jurisdictions thrashing over what used to be settled law whether it applies to national security or personal liability. He's a one-man litigation generation machine. And he has cultivated unblinking support from the GOP even though he's a relatively recent convert. His name appears above the fold in our newspapers of record at least twice per week. He has our closest allies in Europe and Asia sweating bullets over whether he is entrusted with our nation's secrets. He's secured his place in the history books, that's for sure. Right up there with certain other megalomaniacs.