This week, everyone is focused on Fulton County, Georgia, and district attorney Fani Willis. We don’t expect an indictment before Tuesday, for the simple reason that several witnesses have said they have received subpoenas to testify in the grand jury and grand jury testimony must be complete before the indictment is voted on. Tuesday is the earliest we should expect to hear anything out of Atlanta, unless something squirrely is going on, like multiple indictments.

But Georgia isn’t the only place where important legal developments are underway. In Alabama, we’re waiting to see if a three-judge panel will rebuke the Alabama legislature, which refused to comply with a decision from the Supreme Court in Allen v. Milligan, requiring it to redraw Alabama’s districts in a way that didn’t discriminate against Black voters. Unlike the usual federal case that is heard by one judge at the district court level, redistricting cases like this one are heard initially by a panel made up of two district judges and an appellate court judge. The panel has set aside the entire week to hear from the parties. The new map adopted by the Republican supermajority in the Alabama legislature does not create two districts where Black voters have the opportunity to elect candidates of their choice, as the Supreme Court said they must, based on 2020 census data that showed maps were drawn in a way that unconstitutionally diluted Black voting power in the state.

I’ll be sending out a separate explainer for the hearing first thing tomorrow morning, in the form of five questions answered by my good friend, Alabama Democratic state Rep. Chris England. Although Five Questions is a feature that’s usually just for paid subscribers, the impact of this Alabama case on all of our rights is highly significant, and I’m going to make the post available for everyone, since this hearing may not get the coverage it deserves this week, in light of all things Trump.

As Alabama Democratic state Sen. Merika Coleman told me, “Had Democrats defied a court order in the same manner, the Republicans would be screaming, ‘Lock them up!’” She hopes the court will appoint “a special master to redraw the congressional map to produce two minority-majority districts so Black Alabamians have the real opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.” We’ll have more about what to expect from Rep. England in the morning. He got straight to the point of why Alabama Republicans refuse to comply with the Supreme Court’s decision in a recent tweet, which also explains why this is a matter that folks outside of Alabama should be paying attention to as well.

And just one more tweet, because when Chris gets going, he tells the truth with no holds barred.

And, not to forget, while the grand jury investigating Trump’s election stealing activity in Washington, D.C., has already returned one indictment against the former president, it is still at work.

One of the most interesting parts of the January 6 committee hearings involved the fraud perpetrated on Trump donors, who were solicited even after it was clear the election was lost for funds to keep litigating. So it’s fascinating when Rudy Giuliani’s longtime colleague Bernie Kerik is questioned about this. Kerik, formerly appointed New York City Police Commissioner in 2000 by Giuliani, later spent three years in federal custody after he was convicted in 2010 on eight federal charges, including tax fraud. Trump pardoned him in February 2020. The current indictment does not include any charges related to whether Trump or his PAC violated federal law by raising money off of false claims of voter fraud.

We know that the D.C. grand jury cannot be doing more work on the current indictment, so they’ve got to be investigating additional charges or additional defendants (like the six unindicted co-conspirators). We could hear more from them at any time, although that could mean complications for Jack Smith’s let’s-get-it-to-trial-fast strategy.

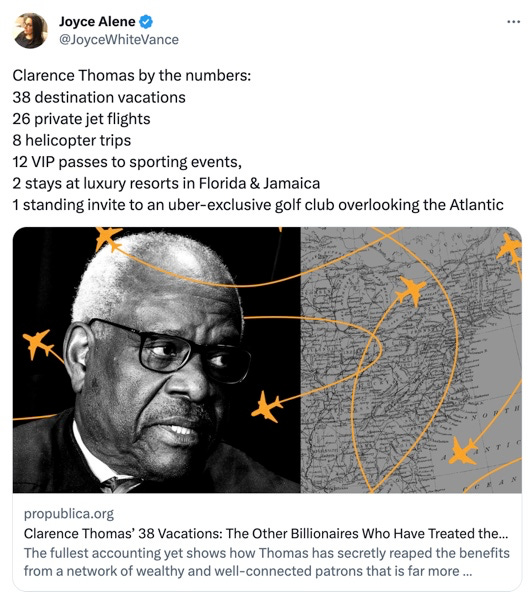

Last week, additional reporting on Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas went by with scarcely more than a momentary whiff of concern. More vacations, more billionaires. ProPublica’s reporting continues. It seems that his ethical improprieties are so many and so common that they roll right off of the radar screen, too hard to keep track of. But Thomas should not get a pass.

The Court could impose ethics rules on itself if it wanted to—the same ones that apply to every other federal judge in America. It could do it tomorrow, with little fanfare. Increasingly, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the only reason they don’t do it is because they don’t want to have to abide by the rules other judges live with.

If that’s not stunning, stop for a moment and read it through a second time. This is a Justice with life tenure on our nation’s highest court. His situation must be addressed, although ultimately the issue is about more than individual judges—the Court as an institution must vigilantly protect its legitimacy in the eyes of the public. It is not doing so. The lack of a code of conduct is an institutional issue that must be addressed.

On Friday, the issue got a bit of new life when five members of the House of Representatives wrote to Attorney General Merrick Garland and asked him to investigate. Jerry Nadler (D-N.Y.), Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), and Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) asked for investigation into Thomas’s "consistently failing to report significant gifts he received from Harlan Crow and other billionaires for nearly two decades—in defiance of his duty under federal law," pointing to a law that requires Justices to make financial disclosures. They wrote, "No individual, regardless of their position or stature, should be exempt from legal scrutiny for lawbreaking.” While we shouldn’t expect any comment from DOJ at this point, there is little question investigation is merited.

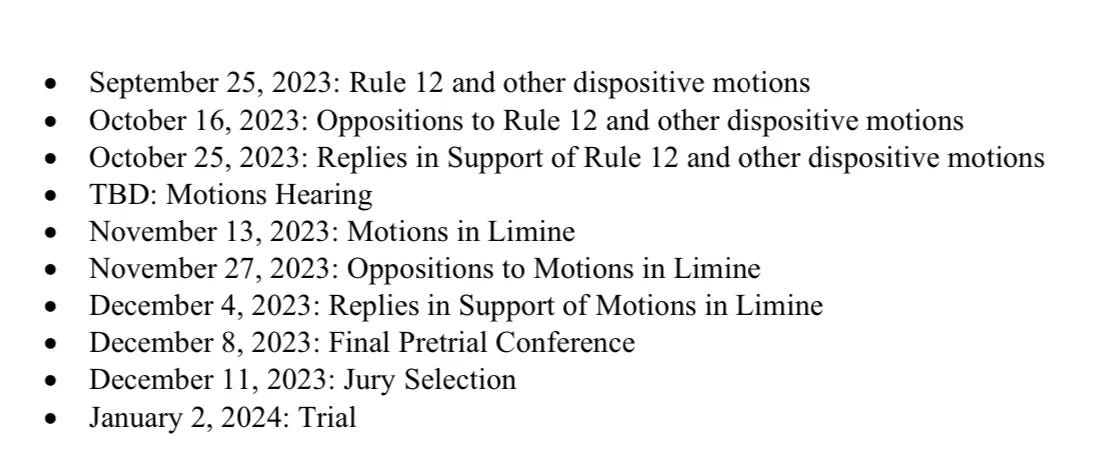

Finally, an apology from me. One of my commitments to you is that I’ll make legal proceedings comprehensible to the non-lawyers among us. Maureen was nice enough to make sure I understand I didn’t do a good job of that last week. She wrote, “Many of your readers are not attorneys. But, you explain things we can understand. But today, I became confused when I read Smith's proposed calendar because I don't know what ‘Rule 12’ means; nor do I understand ‘limine’. I googled the terms but need a better definition; and I need to understand their meaning as it applies in this case.”

Maureen is absolutely right, and we had a lovely exchange of emails. Her questions relate to this item from last week, showing us the government’s proposed schedule leading up to a January 2, 2024 trial date—still no ruling from Judge Tanya Chutkan.

Let me back up and clarify the legal stuff.

First off, Rule 12. When lawyers work on cases, they have two different kinds of concerns. The first is substantive: What is the law regarding defamation, for example, or what are the elements of a burglary charge? The second set of concerns are procedural: How do I file a complaint in a civil case? How many days after a defendant is arraigned does the government have to try the case?

Rule 12, in the government’s proposed schedule, refers to the rules that govern these procedural issues. In the federal system there are separate sets of rules for civil and criminal procedure, so it’s important to know what kind of case you’re talking about and refer to the right set of rules. States have their own rules about procedure.

You can find an online version of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure here, if you ever want to refer to them.

Rule 12 governs pleadings and motions the parties file before the trial begins. There is a long list of motions that have to be made before trial. (If they aren’t, the party that could have made them waives the right to do so later on, although a court “may consider the defense, objection, or request if the party shows good cause for failing to raise it earlier.”) They include motions arguing the government filed the case in the wrong place (venue) or waited too long. Motions arguing the prosecution did something improper, like targeting the defendant when other people who engage in similar conduct aren’t charged or singling out a defendant for vindictive reasons, make the list, as do errors made during grand jury proceedings. Defendants frequently file motions to limit (“suppress”) the evidence the government can put in front of the jury at trial (for instance, by arguing that the government obtained the evidence through a search warrant that wasn’t properly supported or that agents searched places they weren’t entitled to by a warrant). There are also motions about the scope of the discovery the government is providing to the defendants; defendants may argue that the government is withholding information it should turn over to them. In other words, there are a lot of issues to litigate in this pretrial stage of proceedings.

In federal motions practice, the party that makes a motion (“the proponent”) offers their argument. The other side gets to file a “response,” and then the proponent gets to “reply.” You see that process in the government’s proposed schedule, and this is among the reasons that cases can take maddeningly long to move forward. For almost all disputes between the parties in a case, whether it’s over a pretrial calendar like this, an individual motion, or the appeal of a case after there is a conviction, this three-part process of motion and responses is followed. Due process requires time. The government’s proposal is to take up a full month for briefing—that’s reasonable—with any necessary hearings to follow.

Then there are motions in limine. “In limine” is from the Latin for “at the start” or “on the threshold” and refers to motions made before trial. Often, they can be taken up a few days before or even the morning of trial in a simple case. Here, the government’s proposed schedule calls for them to be heard the month before trial. Motions in limine help to establish the rules of the road for trial and clarify any issues in advance so that nothing happens in front of the jury that could cause a mistrial. Or at least that’s the theory. A classic example of a motion in limine could arise in this case if Trump wants to argue at trial that the prosecution “violates my First Amendment rights,” but the judge determines before trial that, as a matter of law, Trump’s First Amendment rights haven’t been violated and there is no factual issue for the jury to consider in this regard. The government would file a motion in limine asking the judge to order that no mention of the First Amendment issue can be made by the defense or any of its witnesses during trial.

Motions in limine are used primarily to prevent juries from hearing inadmissible or highly prejudicial evidence, and they can be brought by either side. Once a jury has heard evidence of that nature, it can be difficult for them to set it aside and ignore it when making their decision. As courts like to say, it’s hard to “unring the bell.” So alerting the court to these issues before trial and seeking a resolution in advance is advantageous to everyone. Or at least to everyone who isn’t hoping for a mistrial, which delay the proceedings even further.

Hopefully that helps to clarify what we can expect to see as these cases move forward.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

wish you had a "love" button besides just the like button.

As always, thank you for your clarity.

Clarence Thomas is either truly as unclear on the laws as he claims and therefore does not belong on the court, or he knows exactly what he has been doing and he does not belong on the court. We'll get to him next, but I want to channel Jack Smith's focus.