Thursday was the last “opinions” day of the Supreme Court’s 2021-2022 term. While the term continues until the Court’s new term starts on the first Monday in October, the Court is in recess over the summer. We won’t hear as much from and about them (and thank goodness for that), although some summers are eventful. For instance, the Court might hear an emergency request in a high profile case to stay an order issued by a lower court (to keep it from going into effect while litigation about whether it was correct is briefed and argued more fully), which could produce a “shadow docket” order.

In September, the Court will have the long conference, where it considers whether to hear the cases that have been piling up on the Justice’ desks. There have to be four votes for the Court to take a case. The rough numbers the Court provides suggests that it will receive 7,000 to 8,000 petitions each year and accept just around 80 cases for argument.

You may find it interesting to take a look at the Supreme Court’s website, which is a little bit difficult to navigate but full of interesting information if you know where to find it. The FAQs, in particular, take on some of the most fraught issues surrounding the Court in such a straightforward, factual manner that it makes the institution appear blissfully ignorant of the controversy swirling around it these days — the most recent Gallup Poll says only one in four Americans have confidence in the Court, a low watermark in its history.

For instance, here’s how the Court responds on the issue of how many justices there are. The Court says:

“The Constitution places the power to determine the number of Justices in the hands of Congress. The first Judiciary Act, passed in 1789, set the number of Justices at six, one Chief Justice and five Associates. Over the years Congress has passed various acts to change this number, fluctuating from a low of five to a high of ten. The Judiciary Act of 1869 fixed the number of Justices at nine and no subsequent change to the number of Justices has occurred.”

Good basic factual info here. Very germaine to the ongoing debate about whether the Court should expand. And now that the Court’s conservative majority is done playing politics (while maintaining it doesn’t do that) for the term, perhaps we can spend some time over the summer reading and thinking about possible fixes for the public’s abysmally low confidence rates. My views on expanding the Court have been evolving and I hope we can all discuss and share our views over the summer.

That’s as far as I can go without discussing some of the bad news from this week (but I offer a cute video of my chickens from when they were babies as temporary relief; that’s Poe on top of the feeder). The Court saved, as is its practice, two of its most significant cases for its last opinion day, Thursday. Yes, Bruen, the gun case, was a thunder clap and Dobbs has settled over the country like a dark cloud. But West Virginia v. EPA, the case I flagged for you last Sunday in “The Week Ahead,” less heralded, certainly less broadly understood, will have long term, deleterious impacts on the country, even more so because it has largely slid in under the radar this week with SO much other news.

Even though Congress literally named the EPA the Environmental Protection Agency, a 6-3 majority, with Chief Justice Roberts writing the opinion, held the EPA lacked authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions from power plants.

Or, as Missouri’s Attorney General, Eric Schmitt put it,

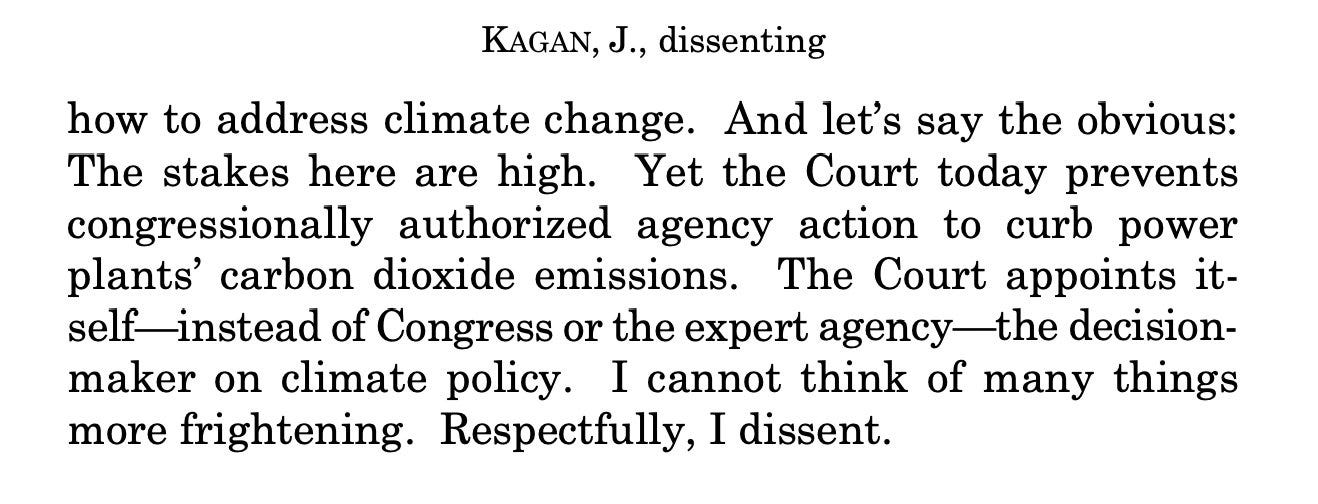

As we suspected at the start of the week, Roberts used the "major questions doctrine" to hold that the EPA lacked the power to turn energy generation towards cleaner sources to effect emission caps. You could read the full opinion here if you wanted to, but honestly, if you’re inclined to look at it, just read Justice Kagan’s dissent. Her disgust with the conservative majority’s results-oriented jurisprudence has finally boiled over:

“Some years ago, I remarked that ‘[w]e’re all textualists now.’ It seems I was wrong. The current Court is textualist only when being so suits it. When that method would frustrate broader goals, special canons...appear as get out-of-text-free cards."

She’s referring to the special appearance of the once rarely used “major questions doctrine,” which the Court trotted out again, after using it last year to end the pandemic eviction moratorium and stop the administration from requiring large business to vaccinate employees.

The application of consistent legal principles, like textualism, may not always lead a judge to the result she might personally prefer. But that’s the point of having a rule of law with consistent approaches that lets it make decisions about difficult issues. To act otherwise makes the Supreme Court look more like a mini-legislature, making policy without any accountability to voters.

The new conservative majority on the Court — this was its first term in full sway following Justice Barrett’s confirmation in the middle of the 2020 election — uses a results-oriented jurisprudence, willing to abandon well-grounded legal principles when they lead to the “wrong” result. The hypocrisy has been apparent in abortion cases all term, with the Court finding ways to make abortion inaccessible even before it reversed Roe v. Wade.

[You doubtless remember the amazing spectacle when the Court threw its hands up in the air and said there was nothing it could do about Texas’ “vigilante justice” approach to abortion, which let pretty much anyone harass a Texas resident who had an abortion and sue everyone who helped for $10,000. Same in voting rights cases, where the Court has contorted itself to strip most of the remaining teeth out of the Voting Rights Act.]

So, Justice Kagan was not wrong to be critical of the majority in her dissent in the EPA case. I fear we will see similar comments from her in the future, as states’ Attorneys Generals challenge the work of executive branch agencies in other areas. Think public health, where we face so many challenges, including those brought on by climate change.

The Supreme Court closed out the week by granting certiorari (pronounced sir-she-er-ari in my part of the country) in Moore v. Harper, a case about elections. That means the case will be briefed and argued next fall, with a decision by mid-2023, meaning this new law will impact the 2024 election.

The issue is whether state legislatures can make decisions about federal elections and override any efforts to review those decisions by the state’s courts on questions of state law (the so-called "independent state legislature doctrine"). If you think that sounds a little bit familiar, it’s because its frighteningly close to Trump’s 2020 Green Bay Sweep/fake electors plot, which involved convincing state legislatures to set aside the votes of their citizens and declare Trump the winner. If the conservatives on the Court full-bore adopt the urged interpretation of the ISL theory, it could be ballgame in 2024, permitting state legislatures to call elections for the candidate of their choice (I’m making that sound slightly easier than it is, they would probably need some basis for this, like, say, phony allegations of election fraud by Democrats), without any prospect of review by pesky state courts that might object to their anti-democratic decision-making.

This prospect is particularly alarming, since, at the moment, 30 state legislatures are Republican-controlled, including some key battleground states like Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Michigan. It’s really the Trumpiest thing of all — make your crooked scheme to steal elections the law of the land.

Many pundits view the Court’s decision to hear this case as a bad sign. But, does a Court whose integrity is already deeply damaged want to issue an opinion that makes our votes meaningless? How does Justice Thomas sit on this case in light of the conflict posed by his wife’s activism? Perhaps the Court will use this case to draw some lines in the sand when it comes to voting.

Admittedly, there’s nothing to suggest optimism here other than the fact that even some of the conservative members of the court may find it unpalatable to thoroughly shred the right to vote. So to the extent this is optimism, it’s optimism grounded in cynicism about the Court. Moore will bear careful watching. The Court has rapidly eroded voting rights since its 2011 decision in Shelby County v. Holder (I wrote about that case a couple of years ago here). The Court returns to Alabama next term to hear another voting case, this time about redistricting, that likely results in more damage to the Act’s ability to protect voters’ rights.

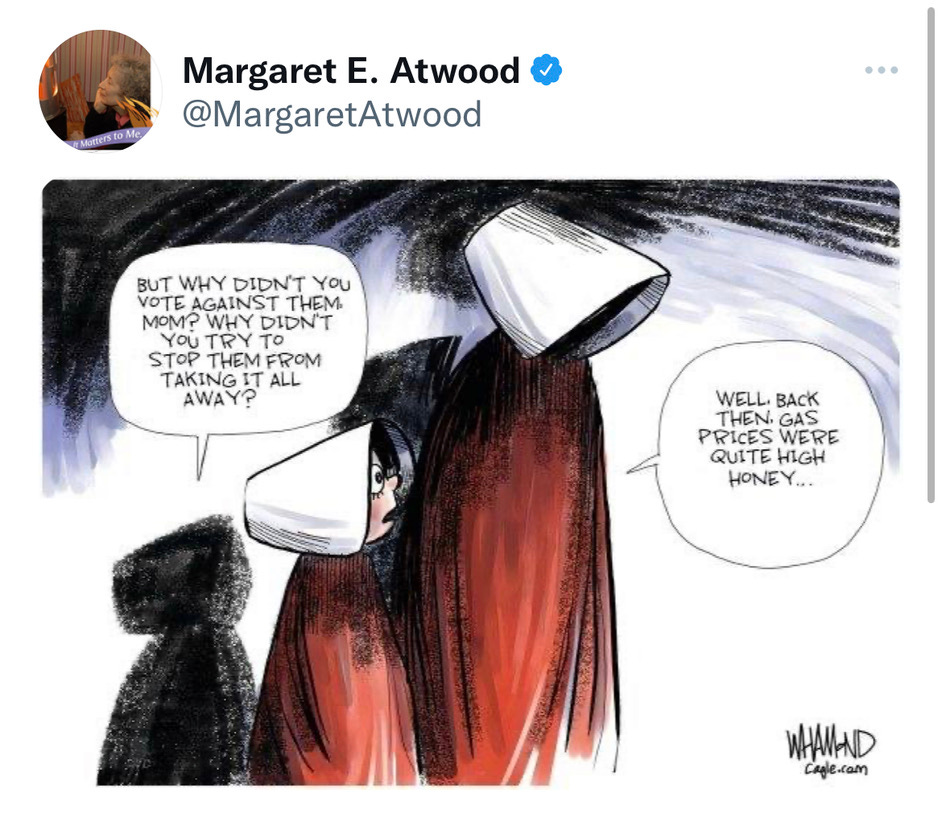

If all of this has you thinking that who you vote for and who controls your state legislature is really, really important to what your future looks like, then you’re dead on track. We can all make sure everyone we know is registered and help people understand who the candidates they will choose from in November are and where they stand on these critical issues. If you start to feel desperate, convince just one more person to be an informed voter. Margaret Atwood, of course, nailed it.

We’re in this together.

Joyce

Share this post