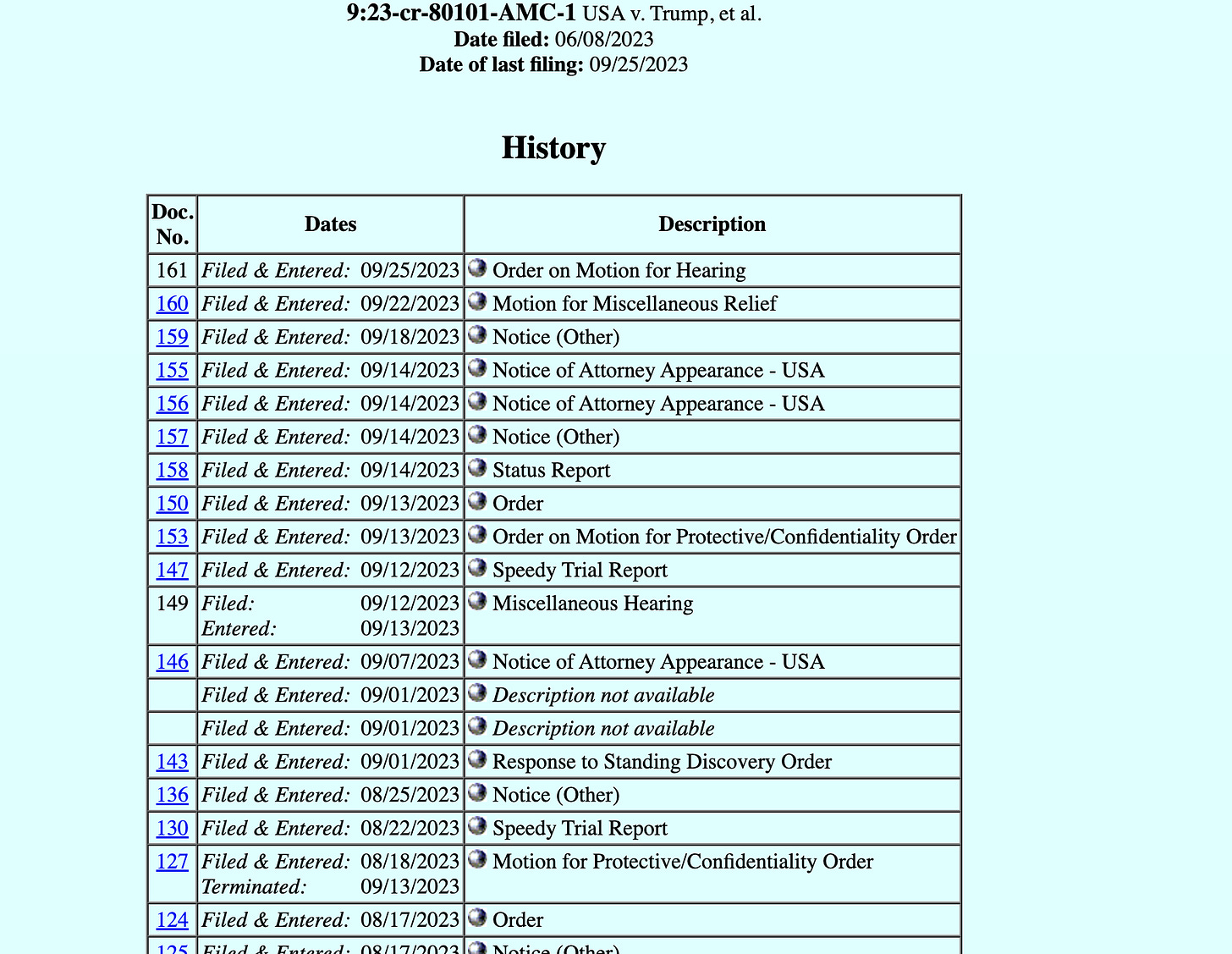

Today, Judge Aileen Cannon in the Southern District of Florida finally ruled on the special counsel’s request to hold Garcia hearings to resolve potential conflicts of interest the lawyers for Trump’s two co-defendants in the Mar-a-Lago case may have, based on their representation of other witnesses. As we noted last night, Judge Cannon had still not ruled on that motion, despite the fact that it had been fully briefed and was ready to go. But today, an entry showed up on the docket for the case on the PACER website (which stands for Public Access to Court Electronic Records), reflecting she had made a decision.

You’ll find it there at the top, item #161, Order on Motion for Hearing. See all the other entries with blue underlined numbers? Those are hyperlinks to the court’s written orders. What’s surprising here is that while the parties fully briefed this issue, Judge Cannon chose to rule in the form of a paragraph-long “minute entry” on her docket, which doesn’t explain how she views the facts or supply any legal reasoning for the course of action she decided upon.

The special counsel requested that both of Trump’s co-defendants, Walt Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira, have Garcia hearings. Here are the special counsel’s key points and the ask of the court:

A Garcia hearing is appropriate given that an attorney who cross-examines a client who is a witness in another client’s case inherently encounters divided loyalties.

The government doesn’t seek a specific remedy, but is giving the court notice of the issue, which it says is consistent with its responsibility to promptly notify the court of potential conflicts, so that the court may conduct an appropriate inquiry under Garcia.

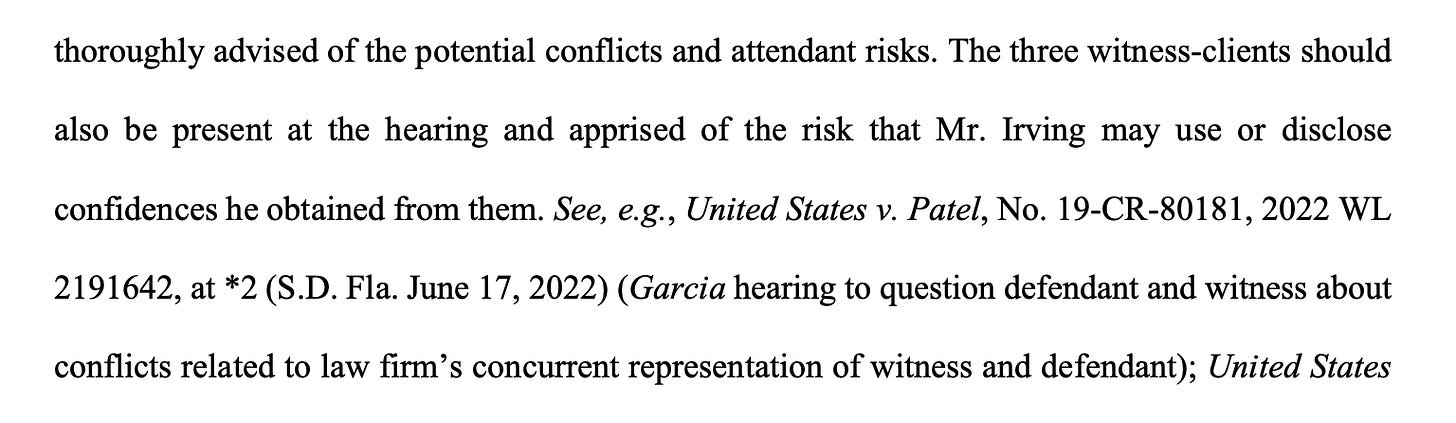

A hearing would permit a colloquy with Mr. Irving’s clients [the lawyer for De Oliveira and other witnesses] to inform them of potential risks and inquire into possible waivers. A colloquy is a formalistic question and answer exchange between a judge and a party to the case that is used to ascertain whether the defendant understands their rights and the court proceeding they are involved in. The classic example is the colloquy when a judge accepts a guilty plea from a defendant.

The special counsel suggests that the Judge may want to have independent counsel present at the hearing and available to advise Mr. Irving’s clients regarding the potential conflicts, should they wish to receive that advice.

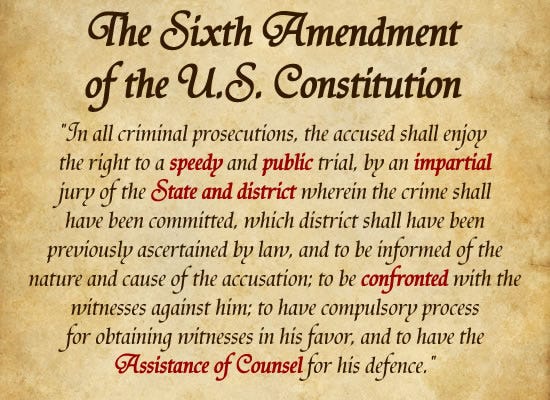

The underlying legal argument the special counsel puts forth is that the Sixth Amendment guarantees a criminal defendant the right “to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense,” which includes a right to have the counsel of the defendant’s choice. But it also incorporates a right to a lawyer who is free of any conflicts of interest, although a defendant can waive that right so long as his waiver is a knowing and voluntary one. That means that before the defendant agrees to move forward with a lawyer who has a conflict of interest, like representing multiple individuals involved in the same case, the defendant needs to understand the full scope and the implications of the conflict. So, courts hold a Garcia hearing to elicit all of that information in a written record, make sure the defendant receives the proper advice, and then permit them to decide whether to waive the conflict or to ask the court to appoint or give them time to retain new counsel. Doing it in this formal manner in court creates a written record in case the issue comes up on appeal.

The prosecution doesn’t have much in the way of options once they learn of a conflict—they must advise the judge. In their brief, special counsel notes that “Some courts describe this as an affirmative “duty” on the Government to bring the issue to the district court’s attention.” Once notified of a conflict, the court has a duty to investigate. After inquiring into the details of the conflict, the court should advise the defendant about it, make sure the defendant understands the risk inherent in the conflict, and give the defendant time to understand and evaluate the risk the conflict poses to them. Perhaps most importantly, in doing so, courts are supposed to make independent counsel available to a defendant who desires to consult, in order to decide what is in their best interests.

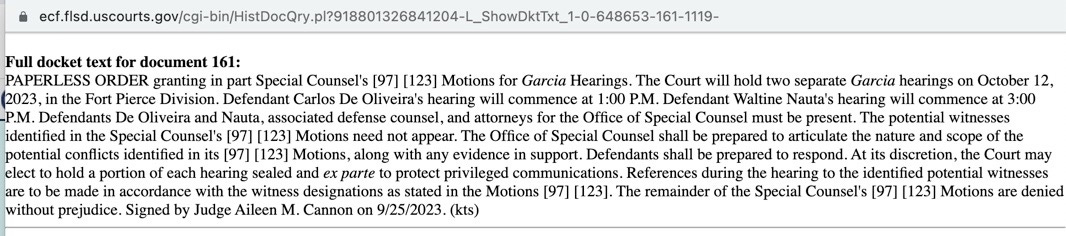

Judge Cannon has not specified she will do that. Here’s her minute order:

She has agreed to hold a hearing, but from what she’s written, it sounds like she intends to rehash what the parties have already provided to her in writing. She does not agree to have independent counsel available for the defendants, or even to have the other witnesses represented by their lawyers at the hearing—they too have conflicts they will need to decide whether to waive or not if they are still represented by the lawyers for Nauta and De Oliveira. They may be essential to discerning whether there is a conflict and what its nature is. And, Judge Cannon indicated she may hold some of the hearing in a courtroom that will be closed to the public “to protect privileged communications.” Although she says her decision is made “without prejudice,” meaning she could change her mind, it’s weak sauce following the extensive briefing and the clear law in this area. She can, and likely will, write an opinion after the hearing, but in advance, when she’s parted company with obvious steps like obtaining independent counsel and having all of the affected witnesses in court, the government and we the people are entitled to her reasoning.

If a defendant decides to waive a conflict and continue with their lawyer, a judge must conduct a detailed colloquy to make sure the defendant has a full understanding of the details of the attorney’s possible conflict of interest and the potential peril it places them in. Almost always in these proceedings, standby counsel is available to answer any questions the defendant has. A failure by the judge to protect a defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel at this stage in proceedings can be fatal to any conviction the prosecution obtains on appeal, and judges have—and exercise in appropriate circumstances—discretion to refuse to accept a waiver from a defendant if they do not believe their rights can be fully protected at trial in light of the conflict.

It’s easy to understand how the representation of multiple people connected to the same criminal allegations can result in a conflict. If an attorney is in the position of cross-examining a witness who is also his client, there are two potential issues. Vigorous cross-examination might result in the attorney exposing the witness-client’s confidences to him, which would be improper. Or, the attorney might feel compelled to pull his punches during cross-examination to protect the client’s confidences or to protect the attorney’s own ability to represent both clients (and obtain a fee from both).

It is telling that Judge Cannon declined to order the witness-clients to attend the hearing, which would have appraised them of the situation as well. The government plainly argued that they should be there (see excerpt below). But because Judge Cannon ruled by issuing a minute order, there is no reasoning that reflects how she arrived at her decision—which seems contrary to clear law. Perhaps she envisions calling them in in advance or at a later time, but it would have been easy to say so, and it’s a striking omission.

So, while the Judge is holding Garcia hearings on October 12 (which is quite a ways out), she does not appear to be on track to have the sort of fulsome proceeding that is both required by law and routine in these situations. The government asked her to: “hold a Garcia hearing with De Oliveira and the three witness-clients present to determine (1) whether and to what extent a conflict of interest arises from Mr. Irving’s concurrent representation of De Oliveira and the three witness-clients; (2) whether De Oliveira or the three witness-clients wish to waive any conflicts and, if so, whether the waiver is knowing and voluntary; and (3) whether the Court will accept De Oliveira’s waiver. The Court should procure independent counsel to be present at the hearing and available to confer with De Oliveira and the three witness-clients, should they so desire.” A similar request was made for Nauta. But at least for now, Judge Cannon is seeing if she can get by with a bare-bones approach.

The question is whether the government will let her get away with it, if she doesn’t change course. With the mid-October hearing date, this matter could be on track for consideration by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals precisely a year after they sharply criticized and reversed Cannon. In that appeal, Trump was trying to prevent the government from using the fruits of the Mar-a-Lago search warrant to advance its investigation.

In its opinion, the court was sharply critical of Cannon, noting at one point that where Trump had failed to provide adequate information upon which she could base a decision, “[T]he district court was undeterred by this lack of information.” Although courts of appeals often find themselves in the position of reversing a lower court’s decision, it’s rare that they do it with the disdain that was evident in the Eleventh Circuit’s opinion. The Court of Appeals focused on the shortcomings in her analysis in that case, pointing to her perfunctory application of the law in a way that just happened to lead her to rule, wrongly, in Trump’s favor. Here, she hasn’t even bothered to draft a written opinion to clarify her thinking, at least so far. She may face a similar fate with the Court of Appeals this year if prosecutors take another appeal to Atlanta.

Why might the Trump camp want to avoid any sort of meaningful Garcia proceeding for his co-defendants? The risk to Trump is that once properly advised of their own situation and the danger they face of going to prison, they might decide to cooperate. Trump’s best chance is to keep any of his co-defendants from breaking from the fold. That’s already happened with Yuscil Taveras, the IT worker who decided to cooperate after a proceeding in the District of Columbia, where the grand jury was investigating him, caused him to decide he was better off being a witness than a defendant. That only happened after the Judge in Washington, D.C. provided him with standby counsel, a federal public defender, who counseled him on his rights. You can see why Trump might prefer that not happen with Nauta, who was in close contact with him throughout, and De Oliveira.

Thanks for being a part of Civil Discourse.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Thanks for your clear analysis, Joyce. I truly can’t decide if Cannon is really that stupid, knowing what happened the last time her decision went to the appellate court, or if she just doesn’t care as long as it protects trump for as long as possible. I guess I need to stop trying to make sense of the far right cultists.

You enlighten! You explain! You entertain! You are extraordinary, Joyce!