I warned you that this part would be excruciating.

The Judge instructed the jury this morning, and they’ve got the case. Their first day of deliberating is finished. They’ve got questions. They’ll return tomorrow for more. This will continue until they either reach a verdict or advise the court that they are hopelessly deadlocked. We are nowhere close to that point.

It’s not possible to predict with any certainty how long a particular jury will deliberate. But this case has always struck me as one where it would be more a matter of days than of hours, and now that has proven to be the case.

Part of the reason the wait on a verdict is difficult, at least for lawyers who have tried cases, is that we tend to rehash the evidence and our arguments and think about what we could've done better. As more time passes without a verdict, we contemplate whether we confused the jury and think about how we could have made the case more clear. That escalates when we start seeing questions from the jury and speculating about why they are asking them. This week, instead of just the lawyers doing that, it is all of us. It’s hard to wait on the jury to do its work.

You can read the jury instructions in their entirety here. The jury does not have access to a written copy of them while they’re deliberating. This is deeply disconcerting to most federal prosecutors, who are used to sending the instructions back with them, unlike in state court here.

Before the Judge got to the specifics of this case, he instructed jurors on the basic elements of law that are common across criminal cases. Chief among them, he reminded jurors of their commitment to decide the case based solely upon the evidence, setting aside “any personal opinions or bias.”

He also talked with jurors about evidence that was admitted for specific or “limited” purposes. He ticked through this evidence, reminding them of the purposes they could use it for and cautioning them against using it improperly to conclude the defendant is guilty. We all understand as human beings that the pull of some of this evidence may be hard to resist, but the law engages in a presumption of regularity, that jurors follow the instructions they are given. Two of the most important areas where the Judge limited the purposes for which jurors could use evidence are:

While David Pecker was at AMI, he entered into a non-prosecution agreement with federal prosecutors and a conciliation agreement with the FEC over campaign finance violations. Jurors can use this evidence to assess Pecker’s credibility and give context to his testimony, not to find Trump guilty.

Evidence of Michael Cohen’s criminal conviction and an FEC investigation into him similarly can’t be used to conclude Trump is guilty. That evidence is to be used to assess Cohen’s credibility and provide context.

The jury instructions also stress the government’s high burden of proof: the defendant is innocent unless the government proves him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. That burden never shifts. And jurors cannot consider the fact that the defendant didn’t testify or hold it against him. The Judge told jurors that if the government fails to meet its burden of proof, they must acquit.

But he explained the burden more fully, telling jurors proof beyond reasonable doubt doesn’t mean proof to an absolute certainty. It’s more than “probably guilty,” but reasonable doubt must be real, not imaginary.

The Judge also talked with the jury about witness credibility. Determining whether witnesses were truthful and whether and how much weight they want to give their testimony is entirely up to the jury. If they believe a witness lied, they can disregard all of their testimony or any part of it. In other words, when the Judge says it’s up to the jury, truly, it is. The jurors were instructed there wasn’t a formula for evaluating witness credibility, and that they should, in essence, use their common sense and life experiences in arriving at these decisions. Jurors can consider, for instance, whether or not a witness had a motive to lie or some bias against the defendant.

In other words, to go to one of the central issues of evidence in the case, whether or not to believe Michael Cohen is entirely up to the jury. That makes it very interesting that their first question to the Judge after they began deliberating was about evidence that could be used to corroborate Michael Cohen’s testimony.

Shortly after 3:00 p.m. today, the jury submitted a note consisting of four requests to review evidence in the case. They want to see:

• David Pecker's testimony about his phone conversation with Trump. (Pecker said Trump called while he was in the middle of a major investor meeting.) This is the meeting where Trump advised Pecker that he, Trump, would speak with Cohen, who would advise Pecker of Trump’s decisions. In other words, Trump held out Cohen as his man on these matters.

• Pecker's testimony regarding Cohen’s efforts to obtain the rights to Karen McDougal’s story about her affair with Trump, and Pecker’s decision after talking with his general counsel that he could not assign “life rights” to own/kill that story. This evidence is particularly helpful in that it could be used to establish that this deal was about protecting Trump from the exposure of this story during the campaign, and not about giving McDougal a fresh start with magazine covers and stories, which was how the deal was structured.

• Pecker's testimony regarding the Trump Tower meeting. Pecker testified that the deal was about protecting Trump from bad stories and pushing out good ones. And it’s important that his version and Michael Cohen’s version of this meeting are consistent.

• Michael Cohen's testimony regarding the Trump Tower meeting

These requests for testimony track the road map prosecutors gave jurors for deciding if Michael Cohen could be believed. It’s dangerous to read the tea leaves, but it’s a cautiously optimistic sign that jurors are working through the evidence in ways that the government proposed. Of course, it could also mean there are one or more jurors who disagree that Cohen can be believed, and other jurors sought this evidence to try to convince them. The bottom line is that we will know what the jury is thinking when they return their verdict.

One important instruction about Michael Cohen involves a matter of New York law, which provides that a jury’s verdict can’t be based solely on an accomplice’s testimony. There must be some corroboration. But that corroboration doesn’t need to be for all elements of the crime, it must simply be sufficient to connect Trump to the crime. So it’s no wonder that the jury’s second question today involved a readback of the jury instructions. They are complicated in their entirety, and this issue of corroborating accomplice testimony is likely to be one of the points where they will want to review the law.

All criminal cases are about the statute the defendant is charged with violating. Here, that is the New York False Business Records statute, which reads as follows, and which we’ve looked at several times:

§ 175.10 Falsifying business records in the first degree.

A person is guilty of falsifying business records in the first degree when he commits the crime of falsifying business records in the second degree, and when his intent to defraud includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof. Falsifying business records in the first degree is a class E felony.

There are complexities with the statute. The Judge instructed the jury repeatedly about how to parse it when they deliberate. One of the key points is the element of “intent to defraud” that “includes an intent to commit another crime” and how that works.

As we’ve discussed, the jury must find unanimously that Trump committed the crime of falsifying business records. They must also find unanimously that he had the intent to commit the other crime, which the state identified as Section 17-152, the crime of "influencing" an election through "unlawful means." The jury must find unanimously that Trump created fraudulent business records and that he did it with the intent to influence an election through unlawful means.

Here’s where it gets especially complicated: There are a number of different unlawful means Trump and his coconspirators could have used to try and influence the election. The law says the jury doesn’t have to agree unanimously on which one of them Trump used, and that’s how the Judge instructed the jury. This is consistent with New York law; there is nothing wrong about this.

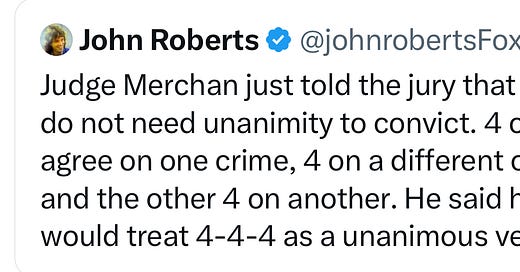

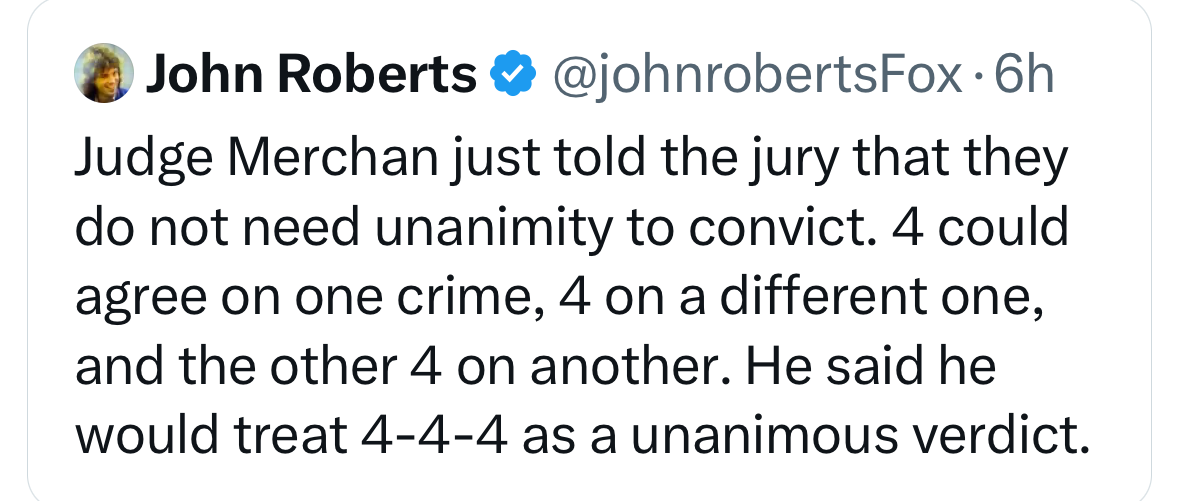

But it led to a furor among Trump supporters, who mischaracterized the instruction the Judge gave, suggesting he gave jurors permission to return a verdict that wasn’t unanimous. This same language was used in dozens of tweets, including this one by a Fox News anchor. And it’s wrong.

The best response came from University of Texas law professor Lee Kovarsky, who was among the many lawyers who took to Twitter to debunk this disinformation. He expressed the answer with surprising efficiency and within Twitter character limits, and is my legal hero of the day. Professor Kovarsky used this example: If a jury is considering a law that says “NO VEHICLES IN THE PARK” and lists a number of different types of vehicles that are prohibited, including mopeds and motorcycles, “all the instruction means is that you need unanimous conclusion of vehicle but not unanimous on whether vehicle was moped or harley.” There still must be a unanimous verdict that an unlawful means was used, but the jury doesn’t necessarily have to agree on which unlawful means it was, although they may. Professor Kovarsky wrote, “As long as you've concluded it's either a moped or a Harley, it still counts as a unanimous finding of the offense.”

The Judge got it right.

The Jury instructions are complicated, and there are 34 charges for the jury to consider—they may well reach different verdicts on different charges. There is no reason to be concerned if they continue to work through the case for the next couple of days. In other words, we’ll continue to wait.

Tomorrow is a Thursday, which means we will likely get one or more opinions in pending cases from the Supreme Court. Today, Justice Samuel Alito told the Senate he will not recuse himself from the Trump immunity case or any other 2020 election-related cases, despite two incidents where his wife flew flags that showed support for Trump’s election denialism and Christian nationalism. Alito blames both flag incidents on his wife, who he said, with remarkable disregard for the ethical implications of these incidents, “is fond of flying flags.” He said he was not. His disdain for anyone who would dare to challenge him was implicit.

Meanwhile, The New York Times reported that Justice Alito’s original story about the incident that led his wife to fly the American flag upside down is inconsistent with the neighbor’s version. Justice Alito said his wife raised the flag after a confrontation with a neighbor. Jodi Kantor at The New York Times, who broke the original story, is reporting that according to the neighbor, that heated exchange happened long after the upside-down flag flew on the Alitos’ front lawn. The flag appeared in the wake of January 6.

Justice Alito has no problem telling American women they lack the right to make decisions about their own bodies and health. But apparently, he can’t tell his wife to take down a flag that calls the integrity of his decisions on the Supreme Court into question. He doesn’t care. He has life tenure and there are no binding ethics rules he must obey.

We will not look away from this. The Court and Justice Alito are a front-burner issue for the coming election. We’re going to keep them in focus here at Civil Discourse. I’m glad we are all here to see this through. Refusing to let this story fade with the news cycle is the start on accountability. If you aren’t already a subscriber, please hit the subscribe button to make sure you don’t miss the newsletter. And thank you to all of the paid subscribers who help me devote the necessary time and resources to this work.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Thanks for all of this analysis. Very helpful. With regard to Alito, what do you make of Rep. Jamie Raskin’s opinion piece in today’s NYT arguing that Congress can and should take action on recusal?

YES! We must keep the dangers of the Supreme Court in front everyone so they can’t continue to mess up our lives.

ALSO: If Trump is found guilty, and I was Judge M, I would give Trump a 2 year suspended sentence. The condition would be that he admit that he was found in guilty in a fair trial and that he refrain from saying anything negative about the entire US system of justice. No complaining about any of his legal problems. If he trashes on any, judge, jury, prosecutor, court clerk, or FBI, he will go to jail. It’s up to him to restrain himself.