Inherent Contempt

It’s quicker than going to court, like Congress can to enforce a subpoena in a civil case. It doesn’t involve referring a case to DOJ, which can (and almost always does when the executive branch is concerned) decline to prosecute a criminal contempt. Inherent contempt is the third type of contempt power Congress possesses—not used since 1935. But Congress used it repeatedly before the civil and criminal contempt laws were passed.

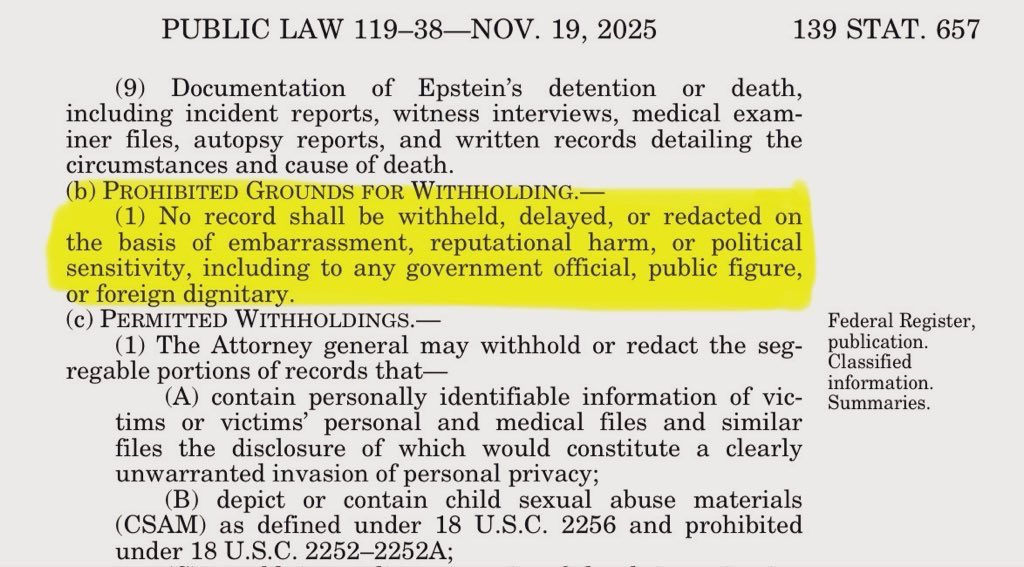

It’s an understatement at this point to say that both Democrats and Republicans in Congress aren’t happy with how Attorney General Pam Bondi is “complying” with the Epstein Files Transparency Act. It’s not just the botched production of documents; it’s also her failure to comply with deadlines, the incomplete production, and the heavily redacted releases, which seem to be offering protection to some of the powerful men who spent time with Jeffrey Epstein, which the Act explicitly prohibits.

House Democrat Ro Khanna and Republican Thomas Massie are leading the charge for the House to bring inherent contempt charges against Bondi, to force her to comply with the law.

Although inherent contempt doesn’t have a constitutional basis, the Supreme Court has repeatedly held it’s an essential part of Congress’s essential legislative powers. In 1927, in McGrain v. Daugherty, the Supreme Court ruled on a case where the brother of a former attorney general received a subpoena for testimony and records from a Senate committee. But he refused to comply, not just once, but twice, so the Senate issued a warrant for his arrest using its inherent contempt power. Daugherty went to court, and the Supreme Court held that Congress has the power to enforce compliance with its subpoenas “to obtain information in aid of the legislative function.” That’s inherent contempt.

“Each house of Congress has power, through its own process, to compel a private individual to appear before it or one of its committees and give testimony needed to enable it efficiently to exercise a legislative function belonging to it under the Constitution,” the Court held. It found that there was support for inherent contempt as “in long practice of the houses separately, and in repeated Acts of Congress, all amounting to a practical construction of the Constitution.”

Khanna and Massey understand that if they seek civil enforcement, they’ll end up tied up in court. DOJ is not going to bring a criminal contempt case against Trump’s attorney general. Using inherent contempt, although it’s a throwback to almost one hundred years ago, would let the House go straight to holding Bondi accountable if a majority of Representatives vote for it—something that remains to be seen and may well turn on how strong public opinion is on the issue. The House doesn’t even need the Senate’s approval to do it.

Inherent contempt has traditionally been used to put offenders in jail, but there is support for the view that it can also be used to impose fines, which is what’s under discussion here—Bondi could be fined $5000 a day, each day, for as long as DOJ fails to comply with the Epstein Files Transparency Action. In an 1821 Supreme Court case, Anderson v. Dunn, the Court suggested that Congress should use “the least possible power adequate to the end proposed,” when invoking inherent contempt. While that may be imprisonment in the case of a person who refused to testify, in a case like this one involving failure to comply with a law, there is a solid argument that a few is the “least possible power” Congress could bring to bear to force a recalcitrant attorney general into compliance.

Whether Bondi would respond is uncertain, perhaps even unlikely, but inherent contempt would be a modest first step toward getting the administration to comply with the law and release the files. If it failed, it would be easier to justify a more serious step like impeaching Bondi, particularly if the public is determined to see the files released. At the end of the day, Bondi has a law license to worry about. The cautionary tale of state bars that disbarred lawyers like Rudy Giuliani who strayed too far from their ethical obligations as lawyers in service of Trump during his first term should weigh heavily on anyone who hopes to have a future, post-Trump.

Inherent contempt “has been described as ‘unseemly,’ cumbersome, time-consuming, and relatively ineffective, especially for a modern Congress with a heavy legislative workload that would be interrupted by a trial at the bar.” Commentators have suggested that’s why it hasn’t been used since 1935. But in the unique circumstance the country now finds itself in, it may be that Congress should decline to let the perfect be the enemy of the good, and reemploy this practicable solution to what otherwise appears to be an intractable problem. Epstein’s survivors deserve justice. Right now, that’s up to Congress.

Thank you for being here with me at Civil Discourse. Writing the newsletter takes time, care, and decades of experience to sort through the noise and explain what actually matters for our democracy. If being part of a thoughtful, engaged community matters to you, I hope you’ll become a paid subscriber. It’s what makes this work possible.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Yes, she is inherently in contempt. Shame on her.

Shame on this administration.

Shame on the majority Republican Congress which has, with only several notable exceptions, failed to fulfill their function as a check and balance, to address needs of Americans and to halt the rampant, illegal acts of this criminal administration, which is destroying our government and our alliances.

History will remember. Americans will remember, when we escape the clutches of this dictatorship, justice will prevail.

Thank you for clear explanation of complex situation.