He's Not Immune

No surprise to readers of Civil Discourse, Donald Trump is not immune from criminal prosecution. Neither he nor Joe Biden can order SEAL Team Six to execute a political rival with impunity. They cannot prevent the smooth transfer of power by abusing the power of the presidency. So says the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. We’ll work through their opinion and discuss what comes next.

“Trump's stance would collapse our system of separated powers by placing the President beyond the reach of all three Branches,” the unanimous decision reads. “We cannot accept that the office of the Presidency places its former occupants above the law for all time thereafter.”

The decision was compelled by common sense. You don’t need a fancy law degree to understand the principles at work here. We are a democracy, after all, and the president was never intended to assume the mantle of a king. It is Trump who wants that result, which was not the intention of the Founding Fathers and certainly is not enshrined in the Constitution and our laws, no matter how Trump tries to contort them.

The panel held that “For the purposes of this criminal case, former President Trump has become citizen Trump, with all of the defenses of any other criminal defendant. But any executive immunity that may have protected him while he served as President no longer protects him against this prosecution.”

With that pronouncement, the court neatly sidesteps the issue of whether a sitting president has immunity from criminal prosecution while he’s in office. That’s helpful here, despite the long-running dispute over whether DOJ got it right when it adopted the policy that forbids its prosecutors, like Special Counsel Bob Mueller, from indicting a president who is in office. It means the appellate court’s decision is less complicated, a straight arrow that should be easy for the Supreme Court to affirm.

As Judge Chutkan wrote in a different case and context, when she declined to let Trump block the National Archives from releasing records to the House January 6 committee, "presidents are not kings, and plaintiff [Trump] is not president." You don’t get to keep the trappings of the office after you leave. Presidents hold the job for four or eight years. After that, they return to being, as the court said here, “citizen Trump.”

When Trump raised his presidential immunity argument before the District Court, Judge Chutkan wrote, “The court cannot conclude that our Constitution cloaks former Presidents with absolute immunity for any federal crimes they committed while in office.” The Court of Appeals agreed, although their language and tone is less sweeping than Chutkan’s, who wrote that Trump’s “four-year service as Commander in Chief did not bestow on him the divine right of kings to evade the criminal accountability that governs his fellow citizens.” The result, however, is the same.

Trump has staked much of his public argument—the incessant social media posts whining that presidents must have total immunity to do their jobs—on the notion that the threat of prosecution after leaving office would hamstring a president from doing his job. The Court of Appeals disagreed. “Instead of inhibiting the President’s lawful discretionary action, the prospect of federal criminal liability might serve as a structural benefit to deter possible abuses of power and criminal behavior. ‘Where an official could be expected to know that certain conduct would violate statutory or constitutional rights, he should be made to hesitate…’ … As the district court observed: ‘Every President will face difficult decisions; whether to intentionally commit a federal crime should not be one of them.’”

The opinion has several key parts that it’s worth understanding.

Jurisdiction

If you’re reading along, beginning on page nine, there are nine and one-half pages of the opinion devoted to a section titled “Jurisdiction” that you won’t hear a lot of TV talk about. That’s because this is a technical legal issue, but an important one, and also one that may have driven the delay in issuing the court’s opinion.

Courts must have jurisdiction before they can hear a case. In this instance, Trump took an unusual interlocutory appeal—an appeal of an issue before trial in a criminal case. The government conceded that was appropriate because if a defendant were to win an immunity issue, then they should not have to stand trial; they would be, in fact, entitled to full immunity from prosecution. But in an amicus brief, a litigant called American Oversight argued that Judge Chutkan’s decision Trump didn’t have presidential immunity couldn’t be appealed immediately and would have to wait until after any trial, so the court lacked jurisdiction under a case called Midland Asphalt v. U.S. At oral argument, Judge J. Michelle Childs seemed possibly persuaded by this view.

As it turned out, the panel concluded it did have jurisdiction to reach the merits of Trump’s appeal. They explained that the decision in Midland Asphalt didn’t apply in Trump’s situation, but it’s a technical and involved argument. Was this the issue that delayed the decision? There’s no way to be certain, but the court spilled a lot of ink and reviewed a tremendous body of case law before concluding they could decide the case before them. This issue is primarily interesting to nerdy lawyer types, but is ultimately of no moment to the court’s substantive decision that Trump isn’t entitled to presidential immunity from prosecution. It’s a necessary first step, but nothing more.

The Substantive Immunity Arguments

Trump offered three arguments to support his claim of immunity, which the court addressed in turn.

The Courts can’t review a president’s official acts because it would violate the separation of powers

The court rejects Trump’s assessment out of hand, noting that it is “settled law” that separation of powers among the three branches of government doesn’t prevent “every exercise of jurisdiction” over the president. Trump argued no federal or state prosecutor or court could “sit in judgment over a president’s official acts.” But the court pointed to prior instances where the courts have reviewed decisions by presidents that exceed their constitutional and statutory authority.

The classic example for lawyers is President Truman’s 1952 decision to seize control of the country’s steel mills, which the Supreme Court rejected because that act was inconsistent with Congress’s will. But perhaps the more telling case was an 1882 matter, United States v. Lee—Robert E. Lee—where the Court ruled that “No man in this country is so high that he is above the law. No officer of the law may set that law at defiance with impunity. All the officers of the government, from the highest to the lowest, are creatures of the law and are bound to obey it. It is the only supreme power in our system of government, and every man who by accepting office participates in its functions is only the more strongly bound to submit to that supremacy, and to observe the limitations which it imposes upon the exercise of the authority which it gives.” Ouch, when the court implicitly compares you to the man who rendered the Union asunder in the Civil War.

More recently, the Supreme Court applied this doctrine to the presidency in a case called Trump v. Vance, where the Manhattan District Attorney at the time, Cy Vance, wanted to subpoena then-President Trump for his taxes. The panel concludes that it doesn’t violate separation of powers when the courts oversee the federal criminal prosecution of a former president for official acts any more than it does when legislators and judges are subjected to criminal prosecution. “Former President Trump lacked any lawful discretionary authority to defy federal criminal law and he is answerable in court for his conduct.”

Policy considerations require immunity to avoid intruding on the functions of the executive branch of government

Trump need only establish one basis for assigning immunity to him to win. Although he bears the burden of proof, which means he has to convince the court he’s entitled to immunity, the government still has to push back against every argument to make sure that no possible rationale for immunity survives.

So, the court moves on to two policy considerations that Trump suggests merit immunity. The court rejects both of them.

The interest in holding people who commit crimes accountable for them outweighs any risk of chilling presidential action or subjecting a former president to “vexatious litigation.”

The importance of upholding presidential elections and completing the smooth transfer of power to a new, democratically selected administration trumps any argument for presidential immunity. The charges Trump faces should be decided in the courts.

In this second argument, the panel, which starts the opinion by saying it’s not intended to establish his guilt or innocence, provides a compelling indictment of his conduct nonetheless. “Former President Trump’s alleged efforts to remain in power despite losing the 2020 election were, if proven, an unprecedented assault on the structure of our government. He allegedly injected himself into a process in which the President has no role — the counting and certifying of the Electoral College votes — thereby undermining constitutionally established procedures and the will of the Congress.” The panel rejects Trump’s “claim” he has “unbounded authority to commit crimes that would neutralize the most fundamental check on executive power — the recognition and implementation of election results,” and refuses to accept his “apparent contention that the Executive has carte blanche to violate the right so individual citizens to vote and to have their votes count.”

It is this last bit that gets to the heart of the matter so eloquently. No president can be permitted to violate the right to vote and then successfully claim he can face no consequences for doing so. Presidential immunity in this regard would seal the fate of democracy.

A former president can’t be prosecuted unless he is first impeached and convicted

Trump’s final argument is the specious one that we have discussed and rejected as borderline frivolous before, the argument that presidents can’t be prosecuted for a crime unless they are first impeached for it and convicted. And yet, in the course of making the argument, he concedes presidents can be prosecuted for some official acts. The only question is under what circumstances and whether the Impeachment Clause works like he says it does.

The court concludes it does not, relying on both the language of the Constitution and the historical evidence around the adoption of the clause. They conclude that the “practical consequences” of Trump’s interpretation of the clause “demonstrate its implausibility,” because it would prevent prosecution of vice presidents and all other civil officers of the United States unless they were first impeached and convicted. The court refers to that as an “irrational ‘impeachment first’ constraint on the criminal prosecution of federal officials.”

Double Jeopardy

Moving to still more frivolous arguments by the former president, the court rejects his claim that the doctrine of double jeopardy bars his prosecution because he was previously impeached by the House of Representatives for what he characterizes as “the same or closely related conduct.”

Double jeopardy prohibits multiple criminal prosecutions of a person for the same conduct. The court points out impeachment isn’t a criminal prosecution—no one goes to jail at the end of it; it’s about whether you keep your job. So, impeachment doesn’t prevent a subsequent prosecution. And, even if it did, Trump was charged with incitement to insurrection in the impeachment, which is different from the claims of conspiracy to defraud the government, interfere with official proceedings, and deprive individuals of their right to vote that he is charged with in the criminal case. Since the charges are different, even if double jeopardy theoretically applied here, it wouldn’t in this specific case.

Trump loses this argument too. It’s a clean sweep against him.

What comes next?

Trump will 100% appeal this decision, which means it’s not over yet. It could be far from over—the pace of any further appeal rests largely with the justices of the Supreme Court. It would take four votes for them to hear Trump’s appeal—they could decline to take the case and simply leave the Court of Appeals opinion in place. But perhaps they will want to put their own stamp on it, since this is an issue of first impression—the courts have never before decided whether a former president has immunity from criminal prosecution for acts committed while in office—and one of great national significance.

Clarence Thomas should recuse. His wife’s involvement in efforts to keep Trump in office give rise to more than the appearance of impropriety, and he should decline to participate in the case. The Court misses an opportunity to begin to restore the public’s confidence in it if he participates in this decision. But I think we all know the odds are long on that.

The outcome of this appeal has to be a foregone conclusion if we’re to remain a democracy. We’ve rehearsed this before—if Trump has immunity from criminal prosecution, so does every other president, including Joe Biden, who could take any steps he chooses to remain in office following the election. The real question isn’t how the Supreme Court will rule, it’s how long it will take them to rule. Judge Chutkan’s March trial date is already a bygone. The issue is whether the Supreme Court will expedite its proceedings to ensure a trial as soon as possible.

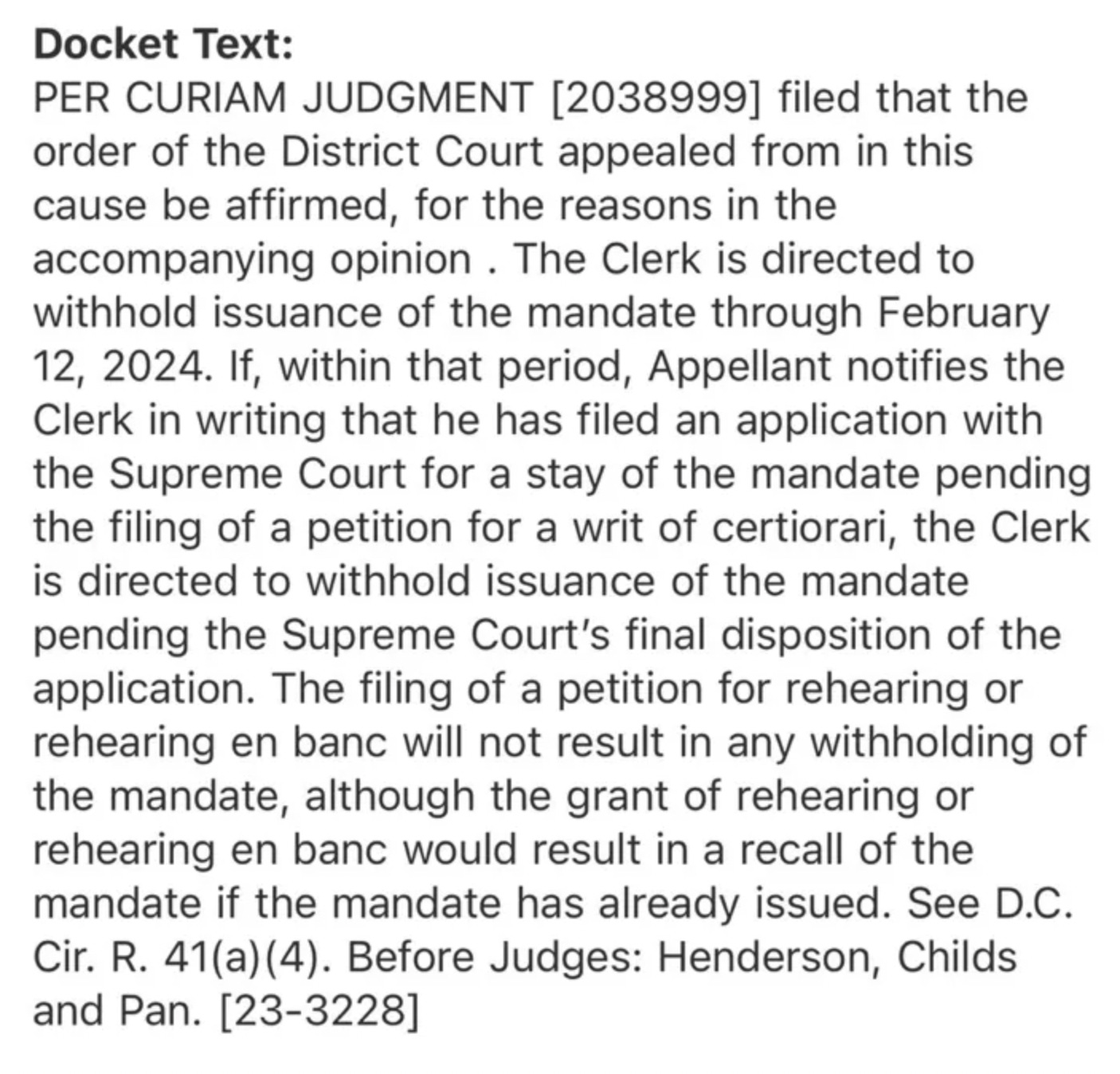

The Court of Appeals did what it could to set that process in motion. Here is the docket entry that accompanied the opinion:

It’s complicated. It means that on the 13th, Judge Chutkan can kick it back into gear and move forward with her case UNLESS Trump asks the Supreme Court to extend the stay (the suspension of proceedings in the district court while the appeal continues) for the time it takes Trump to file his “petition for a writ of certiorari”—his ask that the Supreme Court hear his appeal of the Court of Appeal’s decision. He’s got 90 days to do that unless the Court shortens that time period, which it can do under the rules.

So, there are two separate steps:

Trump must ask the Supreme Court to hear the appeal, which they are not required to do. It takes four justices to agree to hear an appeal.

If the Court agrees to take the appeal, then there will be a briefing schedule, oral argument, and a full opinion on the merits.

Of course, all of this takes time. It can take a lot of it. Or the Court can expedite as it has done with the 14th Amendment case it will hear Thursday, and as it did in earlier cases involving national elections like Bush v. Gore.

It’s worth noting that Trump won’t get a continued stay of proceedings before the trial court if he has asks the full Court of Appeals to rehear the three-judge panel’s decision “en banc,” with all of the active judges on the court participating. That option for additional delay of the trial has been foreclosed by the docket entry above, seemingly representing an agreement by the Court of Appeals that it won’t be party to further delay games by Trump.

The Supreme Court could echo that approach, ensuring Trump’s due process rights are protected without indulging in unnecessary delays. Among the time-saving steps they could take would be to treat Trump’s request for an additional stay, which he must file by next Monday if he doesn’t want the district court to proceed (and he doesn’t) as his request for certiorari—to hear the appeal itself. They could grant it, set an expedited briefing schedule, hear argument later this month, and have the case decided in early March, permitting the trial to get back on track. And as long as I’m going to entertain that fantasy outcome, we can hope the Court will rule 8-0 that presidents are not kings and Trump doesn’t have lifetime immunity, with Justice Thomas sitting it out. But, of course, there are a full range of possibilities where the Court takes the case and doesn’t decide it until late in the term, possibly even the last week in June or the first in July, making it virtually impossible to try the case before the election.

The outcomes where the Justices split their votes are painful for the Republic. Imagine if the Chief Justice and Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh join the progressive wing of the court in declining to hear the appeal, while Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch (or some of them) write dissents from the denial of cert, arguing the Court should hear the matter. Just like it was important for the panel decision in the Court of Appeals to be unanimous, a unanimous decision from the Supreme Court would make it more difficult for Trump to fan the flames of dissent in the country. That’s not to say he won’t try—he obviously will. But it will be much more difficult for him to get traction beyond the core of his base with a Supreme Court that stands for the rule of law in a unified fashion. Let’s hope the Supreme Court will also stand for ensuring the American people get the speedy trial they are entitled to.

When she ruled against Trump on immunity, Judge Chutkan wrote that the prospect of future criminal liability should “encourage the kind of sober reflection that would reinforce rather than defeat important constitutional values.”

“If the specter of subsequent prosecution encourages a sitting President to reconsider before deciding to act with criminal intent, that is a benefit, not a defect.”

The Court of Appeals agreed, and it would be shocking if the Supreme Court departed from that view. The real question is, how long will it take them to get there? Democracy may well hang in the balance. When he was impeached in 2021, Trump told the Senate he shouldn’t be convicted because he could be prosecuted in court after he left office. Now he claims he has total immunity from prosecution. It’s up to the Supreme Court to hold him accountable.

If you’ve made it all the way to the end, thank you for sticking it out. None of this is easy, but it is important. By making the effort to understand, and hopefully to help others understand, we can all do our bit. I keep going back to the court’s emphasis on the importance of the right to vote. It’s hard to believe that we are about to have a man who has been indicted four times on the ballot to lead our country. We’re going to be focusing over the next weeks and months on how we can make sure we stay registered, we vote and our votes count. Thank you for your subscriptions, which make it possible for me to devote more time and resources to this work.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

During my recent, annual visit to see my 94 year old Mom, she insisted we update her voter registration following several hasty moves she’s endured these past few years. Despite all she’s been through, she’s more determined than ever to do her part to “…keep that son of a bitch out of the White House!”

(One of her assisted living facility neighbors has a bumper sticker stuck to his door that reads, “I just want to see Trump spend 11,870 days in prison.” This small facility is in a very conservative, backwater rural area - there’s room for hope.)

Three things:

Love this Court of Appeals.

Don’t trust Thomas to do the right or honorable thing.

Why isn’t Smith trying to get Aileen Cannon removed from the documents case? Her bias is blatant. Please, Joyce, I’d like an answer.