It has been another one of those weeks that explodes with a year’s worth of news in it. Tonight we’re going to focus on the Proud Boys trial, because it’s incredibly important and it hasn’t gotten nearly the attention it deserves with other breaking news competing for its attention. But I’ll flag some of the developments we’ll continue to watch this week:

On the heels of Wednesday’s news that an appellate court in the District of Columbia rejected Donald Trump’s efforts to prevent Mike Pence from testifying before the grand jury investigation that special counsel Jack Smith is running, Pence testified on Thursday for seven-plus hours. Of course, grand jury testimony is secret, and as of the time I’m writing this Thursday evening, we don’t have any details. But chief among my questions for the former vice president would have been whether Trump tried to enlist him in a conspiracy to steal the election like he did with Georgia’s Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. You don’t need much of an imagination to hear Trump using the same tactics, alternating pleading and threatening, to get Pence to join his merry little band of plotters. It would explain why Pence reached out to everyone from former VP Dan Quayle to retired federal judge Michael Luttig—the need for reinforcements. In Georgia, Trump finally resorted to pleading, “Fellas, I need 11,000 votes. Gimme a break.” What might he have said to Pence when it became clear he wasn’t playing along, and could it establish definitively that Trump knew he’d lost and was trying to conspire with others to interfere with the certification of Biden’s win? That seems highly likely if Pence was inclined to tell the truth, the full truth, and nothing but the truth when he testified. Listen to excerpts from Trump’s call here if you want a refresher. Now imagine he’s talking to Pence.

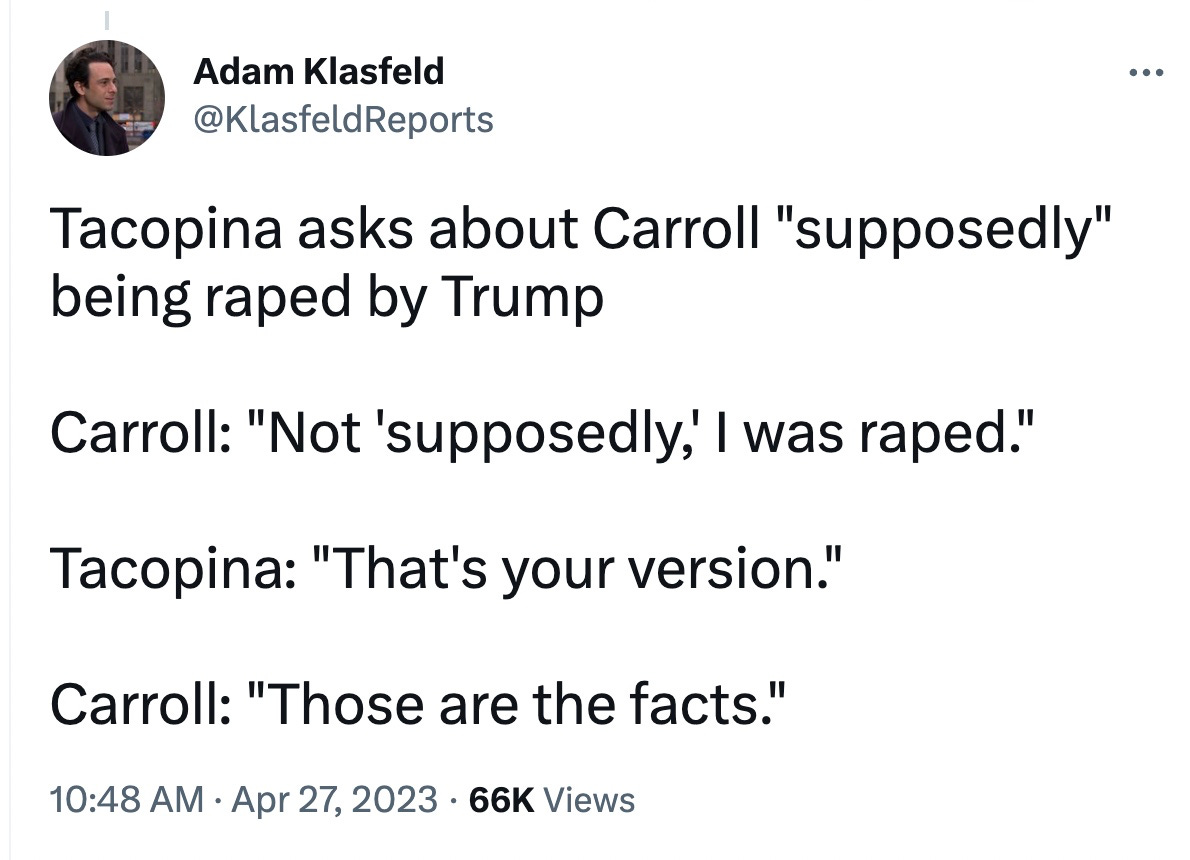

E. Jean Carroll’s trial continued today with Carroll on the witness stand to finish her direct testimony and begin cross-examination. It was every bit as bad as you might have anticipated, with Trump attorney Joe Tacopina suggesting she wasn’t raped because she didn’t scream. Carroll didn’t budge. “I was raped,” she told him. “Those are the facts.” When a lawyer has a rape victim on the witness stand and is cross-examining, it’s a bit of a conundrum. If you don’t press hard enough, the jury won’t have reason to doubt the victim’s testimony. They’ll believe there was a rape. Push too hard and you make the victim sympathetic, and the jury will punish your client for the way the victim is treated. The lawyer conducting the cross-examination has to walk a careful line here. Tacopina managed to fall off the tightrope in both directions, not seeming, from the reporting coming out of the courtroom, to have made significant inroads into Carroll’s credibility, while simultaneously being offensive and boorish and pushing the jury towards supporting her version.

The bottom line here is that if Carroll was making it up, she would have made up a better story. She would have specified a precise year and month, if not a date. In some ways, the more Tacopina pushes, the worse off his client is.

Other stories percolating around this week: The chief justice has refused to appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee to testify. Meanwhile, the full court, all nine of them, issued a letter suggesting that we, the public, should have confidence in their ethical behavior because they told us to. I doubt that will be enough. Disney has sued Florida governor Ron DeSantis, alleging violations of contractual obligations and its First Amendment rights. DOJ filed a lawsuit challenging Tennessee’s anti-trans law, while Montana’s first transgender state legislator, Zooey Zephyr, is working from the hall after she was expelled from the chamber for “decorum” violations. Decorum is the new shorthand for telling people to stay in their place and drink from the watercooler marked for people like them. And there are new developments in the prosecution of Pentagon documents leaker Jack Teixera, whose background, including a fascination with mass shootings, makes one question how he ever got the background clearance necessary to have access to the documents he leaked. There is also news that he tried to obstruct the investigation into his leaks once he learned it was underway.

But let’s put all of that aside to talk about the Proud Boys trial, where the jury is now deliberating. Normally, “Five questions with…” is a feature I do a couple of times a month for paid subscribers. But in the course of working on some questions with Brandi Buchman, an independent journalist who has been in the courtroom every day for the almost four months of the Proud Boys trial, I decided to make this edition of Five Questions available to everyone. Brandi has remarkable insight into what took place in the courtroom.

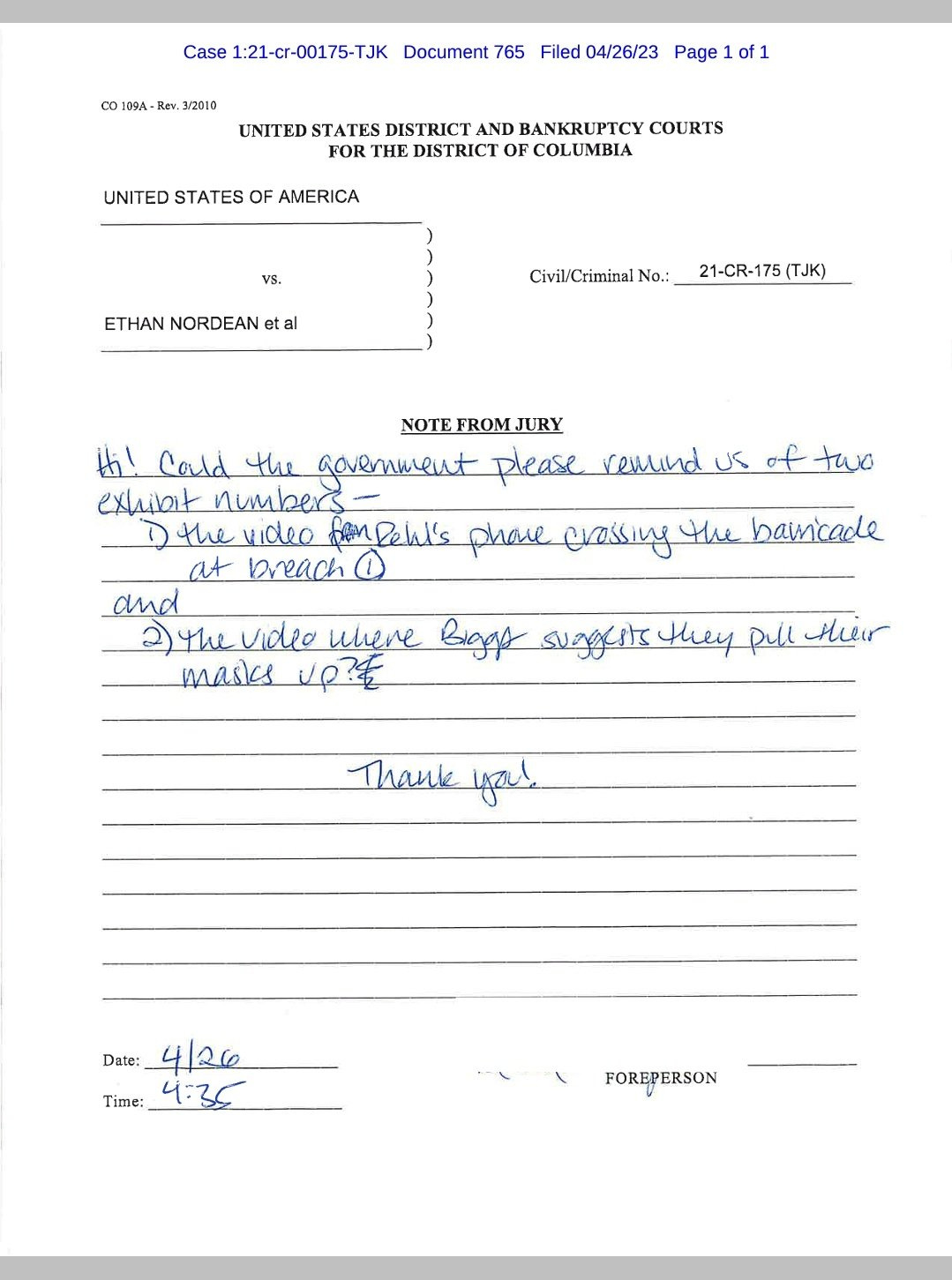

With no cameras in federal courts, and with so much else going on (like the first indictment of a former president), this trial hasn’t always received the mainstream media coverage it deserves. I’ve relied on reporters like Buchman to stay up to date on how the trial was going. Every day, she included little snippets to give you the flavor you’d otherwise miss, like this one from Wednesday, where she shared a question the jury asked the court the same day their deliberations began.

You can see that the jury feels very comfortable with its work. And they seem to be focused on some of the evidence that could be used to justify guilty verdicts.

I asked Buchman five questions about the trial and her work as an independent journalist. Here are her responses.

Joyce: Almost four months, five defendants, multiple charges including seditious conspiracy, conspiracy to conduct an official proceeding, and actual obstruction of a proceeding. It’s confusing. If you had to describe what crimes the government says the defendants committed, absent the legalese, how would you characterize it?

Brandi: At its core, the government alleges that Proud Boys ringleader Henry “Enrique” Tarrio and his co-defendants Ethan Nordean, Joseph Biggs, Zachary Rehl, and Dominic Pezzola came together with an intent to stop the certification of the 2020 election on Jan. 6, 2021, by using any means necessary—including the use of brute force.

This conspiracy against the United States and to obstruct Congress and impede law enforcement was not something that the government alleges was necessarily plotted out point by point or mapped out with grand precision. Instead, they argue that in late 2020, the group’s anger and frustration with then-President Donald Trump’s failure to overturn his election loss in the nation’s courts reached a fever pitch and then exploded on Jan. 6. Trump had named-checked Proud Boys at the presidential debates and told them to “stand back and stand by.” This prompted the group’s numbers to swell, and the Proud Boys national ringleader Tarrio and his co-defendant Biggs set about the mission of tasking their members to look for “real men” and “radical” men who could fight and do more than get drunk and clash with counterprotesters who they dubbed “antifa” when they would attend pro-Trump rallies like they did in D.C. in November and December 2020.

Ultimately, prosecutors say Tarrio formed a secretive back channel for a select group of Proud Boys he dubbed the Ministry of Self Defense, or MOSD, around Dec. 30. This group was allegedly inspired, however, by Trump’s Dec. 19 “will be wild” tweet urging his followers to descend on Washington on the 6th.

The defendants claim MOSD was just a hub for Proud Boys to discuss how they could defend themselves from “antifa” or leftists at impending rallies, like the one on Jan. 6. The Justice Department, however, points to a huge number of text messages and other correspondence that they say indicate the Proud Boys fully intended to use MOSD as a hub to coordinate an attack on the Capitol.

With this intent, the defendants and a slew of other Proud Boys not named in this particular indictment came to Washington. Nordean, Rehl, and Biggs led a marching group of Proud Boys and others estimated to be no less than 100-men strong from the Washington Monument to the Capitol. Tarrio had been arrested two days before and was ordered to stay out of D.C. So on the 6th, he was holed up in a hotel room in Maryland where he watched the riot unfold, celebrated the violence, and texted Proud Boy elders and leaders messages like “Make no mistake. We did this.”

The Proud Boys understood that alone they might not be able to stop proceedings, prosecutors have said, so they riled up the “normies,” or average supporters of Trump’s, in the crowd. Once sufficiently amped up, they are alleged to have initiated the Capitol breach, knocking down some of the first barricades and fences as overwhelmed police scrambled to defend the building, everyone authorized to be inside, and themselves.

Nordean, Biggs, Rehl, and Pezzola all breached the Capitol that day, and Pezzola is unique among his cohorts in that he faces a robbery charge for allegedly ripping a police riot shield violently away from an outnumbered U.S. Capitol Police officer. He would use that shield to bash apart a Capitol window after taking a selfie with it. Rehl, who adamantly denied seeing any violence on Jan. 6 or assaulting police, is alleged to have pepper-sprayed law enforcement after photographic and video evidence of the alleged incident emerged in the trial’s final days—much to his lawyer’s frustration and objection.

The certification of the election did resume following Trump’s incitement of an insurrection, but only several hours after the ransacked Capitol had been cleared by swaths of law enforcement.

The proceedings by Congress were obstructed by the mob that day, and the Justice Department says the Proud Boys were responsible because they considered themselves the “tip of the spear.”

Joyce: What was your impression of the strength of the government’s case? Did the jury seem to be on board? Long cases can be confusing, the evidence doesn’t always come in order, and there’s a risk the jury doesn’t know how all the evidence fits together.

Brandi: I think the government had a yeoman’s task with this case because of the sheer wealth and scope of the evidence and the number of the defendants. Distilling the evidence in a logical way is no easy feat even with a team to assist you, but my impression was they met the moment with what they had at their disposal. It was a long trial, twice as long as the first Oath Keepers seditious conspiracy case, which clocked in right around 30 days. Proceedings in this matter would often get bogged down with objections launched by members of the defense over any number of issues, several litigated pretrial. I worry those near-constant disruptions may have made the flow of information on some days more difficult to follow.

Presiding U.S. District Judge Tim Kelly was a fair judge in that he was always willing to hear from every party on even the most minute issues, but as a result, he often struggled to maintain order—he threatened to put one defense lawyer in “time out” for speaking over him on one occasion!

Defense attorneys seemed to take a mile for every inch Judge Kelly was willing to grant, and sidebars plagued the trial from its start. Midway through, one juror even expressed concerns she was being followed. But when I observed them in the courtroom, they appeared attentive and often were seen taking notes. On occasion, when proceedings were moving at a glacial pace, there were some sagging shoulders and tired eyes in the courtroom, but I think it was hard not to pay attention when some of the most critical and arguably damning evidence was presented.

Joyce: What about the defendants? What was their demeanor like in court? Is there any sense of contrition for what they did, or did you walk away with the sense they thought that their behavior was legitimate?

Brandi: I think the closest thing we got to contrition was when Dominic Pezzola came up on his first day under direct examination and expressed some remorse for his actions. But that was short-lived. By the time he came under cross-examination, he grew combative, angry, and often snide. He told a jury that has listened to evidence for months, a jury that holds his fate in their hands, it was a corrupt trial and the charges were fake. Zachary Rehl’s time on the witness stand was no better. He was combative when fielding questions from the prosecution, and he even lacked credibility when under direct. At one point, he even beggared belief from his own attorney when he said he pushed past barricades at the Capitol because he was looking for stages where people might be speaking. He compared it to a rock concert.

“You’re giving me this look, but it’s the honest god’s truth,” Rehl told his attorney.

I may be wrong, but I think this group of defendants mostly just regrets being in the predicament they now find themselves in. Rehl and Pezzola came off cocksure when not being evasive. I think they are still angry at the system, angry things didn’t pan out how they hoped—planned or not. Tarrio didn’t testify, Biggs didn’t testify, Nordean didn’t testify. But they were frequently busy taking notes and seemed very plugged into proceedings, from my vantage. I often observed Tarrio pass notes to his attorneys or chat with his team’s paralegal. Judge Kelly regularly told the defense table to pipe down because he couldn’t hear the witness or the prosecutors.

Despite the stakes—seditious conspiracy alone carries a maximum 20-year sentence—Tarrio’s demeanor gave me the impression he felt rather self-assured. Nordean and Biggs were often the most reserved in court, but it seemed Biggs most of all. He sat at the very end of the defense table, his face often expressionless and usually with his arms folded across his chest or resting on the table. Pezzola often leaned back in his chair, his eyes scanning the courtroom.

Joyce: Were there any interesting, off-the-record, private moments that you saw?

Brandi: I like to keep my off-record moments off the record! but I will say that watching these particular proceedings close-up will likely stick with me for the rest of my life. There were lots of big personalities in that courtroom. There was much doggedness on both sides. There were lots of little side remarks, some of them humorous, some quite bitter. There was also palpable anger expressed in that courtroom by witnesses. The gravity of Jan. 6 and all that it entailed then, and all it will entail for our country’s future, was palpable.

Joyce: You’re an independent journalist. You were in this courtroom from the very beginning and you’ll be there down to the bitter end. Without cameras in the courts, in the absence of your reporting, we wouldn’t know much about this trial. Because you’re there, interested people (like me) have been able to read your Twitter threads every day and have a sense of what’s going on. Can you talk about the importance of independent journalism, and how interested people can best support you and your work?

Brandi: Independent journalism is incredibly important because, at its best, it can allow a reporter to inform the public in detail about an important story without being hemmed in by artificial parameters. Don’t misread me: solid, meaningful reporting absolutely can and does happen in the so-called “mainstream.” But in my experience, independent journalism can allow one to really focus on a story and focus on it singularly, without distractions that can crop up when you’re a reporter spread thin over several beats and constant deadlines.

Sometimes certain media companies can also define journalism in pretty shallow terms, and unless you’re comfortable outrage-farming with every post or story, it can be hard to convince management to take your work seriously. In short: as an independent reporter, the priority is always the story, never the whims of your manager.

On reporting, one of my very first editors once told me, “Just tell me what happened.” Sounds simple enough, but it’s not as easy as one might think, I’ve come to learn.

But that’s what independent reporting has allowed me to do: I can just tell people what happened, and if telling that story demands I get deep into the weeds, well, good, I do love high grass and there’s no one to stop me from wandering into it.

If people want to support my work, you can help me fund essential research, like court transcript costs, and support a Jan. 6-related project I’m working on and hope to announce very soon here. When I was laid off due to cutbacks mid-trial, support from Marcy Wheeler at Emptywheel let me continue my coverage. She saw the value in my reporting where others simply did not. Without her, I highly doubt I would have been able to pull off going to trial every day until the bitter end.

_____

Many thanks to Brandi for sharing her insights with us. When the jury returns to the courtroom with a verdict, I feel like we’ll be prepared to understand it, between yesterday and today’s editions of the newsletter.

Brandi’s work as an independent journalist makes me reflect that when I moved to Birmingham in 1987, we had two vibrant daily newspapers here. The Birmingham Post Herald shuttered in 2005, and the Birmingham News stopped being a daily in 2013 and no longer publishes a print edition in 2023. I miss those two publications more than I can say. And I’m grateful to all the reporters who continue to inform us—print and broadcast, traditional media and new media, and especially those who follow their own path. People like Brandi, or the folks at ProPublica, whose reporting unveiled the Clarence Thomas scandal, add so much information to what we know and shine a light on the truth. We are very lucky to have them!

We’re in this together,

Joyce

Joyce, Brandi, I’m curious who is paying the defense lawyers for such a long and high profile case? Who are the defense lawyers and what is unique about them? Are they public defenders? Or are they a big DC Firm that commonly defends Republicans? How much are they charging the defendants? If someone else is paying them, is that disclosed to the jury and/or public? Thank you so much for your interview and sharing it so generously.

This Supreme Court taking freebies is crazy. The discussion has been basically: Did a law get broken by not reporting the freebies?

Give me a break. As a Fire Officer and for 1/3 of my career a commissioned police Officer in a major West Coast City, I could not accept a free cup of coffee, let alone a trip on Yachts and Private jets, or having my mothers house bought so she could live rent free.

Many times I was told “on the house” for a cup of plain coffee. I always left twice the cost of the coffee. As a Detective (especially in Chinatown) on a slow night, Homicide, Vice, Arson etc. would go to dinner. I’d pay with a twenty and get twenty In change back. I would leave $30 on the cash register. And make a note in my journal.

Someone explain to me how I can sign up for free international travel and give my mother free rent legally.

🤦♂️🤦♂️🤦♂️